1893 – 1918

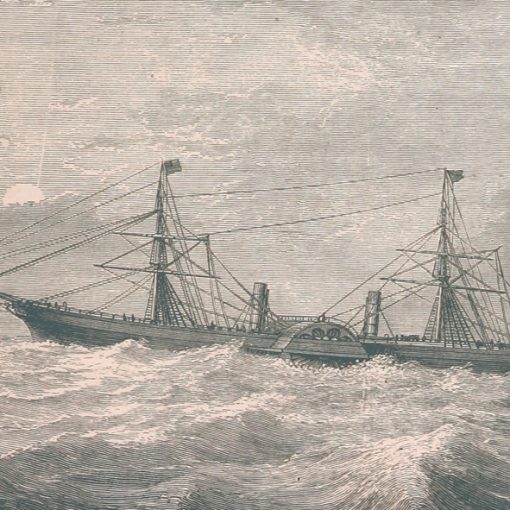

By the end of the 19th century, steamships were really beginning to look like ‘real’ steamships. But one could still make out some resemblance to the old sailing vessels, even on some of the newest ships built. The holder of the Blue Riband, the Inman & International Line’s City of New York, had a clipper-like bow and masts ready to take sails if ever necessary.

But the entry of Cunard’s new Campania and Lucania took the ship design a little further towards the ‘genuine’ steamship appearance. The Campania was launched on September 8th 1892, at the Glasgow shipyards of Fairfield Co. Ltd., by the Cunard chairman’s wife, Lady Burns. The Campania and her sister Lucania was built with the purpose to retrieve the Blue Riband from the City of New York and City of Paris, which had taken the award from Cunard’s Etruria in 1889.

After her launch, the Campania was to be fitted out. This took some time, and the ship was not ready for her maiden voyage until April 22nd, 1893. The Cunard Line still operated out of Liverpool as their main terminus, and the Campania would serve on the Liverpool-New York run. Before setting out on her premiere crossing, the Campania must have been an awe-inspiring sight. Her bow was almost not raked at all, and seemed to be cutting the water surface like a knife. Her massive funnels, each 19 feet in diameter, were raked backwards and gave the ship an all out ‘speedy’ appearance. The bridge was of the new kind; it was something completely different from older ships. It rose high above the other decks, and was situated towards the bow. With the steamships getting bigger, the helmsman had to be high and far forward to see over the forecastle. In terms of propulsion, the Campania was fitted with ten-cylindred triple-expansion engines linked to two propellers. She was actually the first in the Cunard fleet to be fitted with twin screws, a feature introduced on the North Atlantic run by Inman & International Line’s City of New York and City of Paris.

Finally, the Campania slipped her moorings and set out on what was anticipated to be a record crossing. But the new vessel could not beat the City of Paris’ 20.7-knot westbound record, at least not on her first crossing. However, on her return trip she crushed the City of New York’s eastbound record, and the Blue Riband was partly back in Cunard’s possession. And it would not take long before the westbound record was beaten. The Campania was a true success.

In September of 1893, the Campania was given a running mate in her sister Lucania, launched on February 2nd, 1893. The Lucania proved to be the slightly faster ship, taking the Blue Riband from her older sibling the following year. She would keep the fabled award until the entry of Norddeutscher Lloyd’s Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse in 1897. With their 22-knot service speed, the two Cunarders provided an efficient Liverpool-New York service. The two ships retained a trusted reliability, and it was not until July of 1900 that an accident occurred. Unfortunately, that accident was a rather serious one. On an eastbound crossing, the Campania encountered heavy fog 207 miles west of Queenstown and was brought to a halt to wait for the fog to lift. The next morning, on July 21st, the Campania collided with the barque Embleton, cutting right through it like a knife. 11 out of the Embleton’s 18-man crew were killed in the collision, and the starboard side of the Campania had taken a rough beating. The ship could be repaired quickly though, and set sail for New York again on July 28th.

1901 was a quiet year for the Campania, but still a historic one when she became the first ship ever to be fitted with a Marconi Wireless Telegraph. Four years later, the Campania again suffered from bad luck. While en route in the middle of the North Atlantic, a rogue wave hit the ship and swept five steerage passengers into the sea. They could not be saved and in addition another 29 people was hurt in the crash. For the first time in history, the Cunard Line had lost passengers through an accident.

In 1907, after 20 years of German dominance on the high seas, Cunard struck back. The entry of the Lusitania and Mauretania was an immediate success, and the two former record-holders Campania and Lucania were now getting old. Then, two years later, the Lucania was destroyed by a fire. Now the Campania was a lone sister. Although the two new ocean greyhounds could easily maintain the company’s Liverpool-New York service, the old Campania was kept on. On April 14th, 1914, she made her crossing number 250. After that she was briefly chartered to the Anchor Line. Campania’s days appeared to be numbered, but the outbreak of World War One gave her the opportunity of a second career.

Although Cunard had already sold her to scrappers, the Admiralty thought that the Campania could come to good use. She was bought and subsequently converted into an aircraft carrier. Her forward funnel was removed and replaced by two smaller smoke pipes and a 160-foot wooden flight deck was added at the stern, making her capable of carrying ten aeroplanes. On April 30th, 1915, she left Mersey to converge with the grand fleet in Scapa Flow. A few days later, the Campania once again wrote history when she became the first Royal Navy vessel to launch aircrafts whilst under way. The Campania was a success as an aircraft carrier, and soon returned to Mersey to have her flight deck lengthened to accommodate more planes. She then returned to Scapa Flow, but could not participate in the famous battle of Jutland because of engine troubles.

The war raged on with the Campania working from Scapa Flow. In the autumn of 1918 she was operating in the Firth of Forth. The sad end of this great ship would come on the morning of November 5th, 1918. The Campania was lying at anchor in the Firth of Forth, and winds were very strong. Suddenly, the ship began to drag anchors. She collided with the nearby battleship Revenge, and a hole was torn up in the Campania’s hull. The ship started to settle by the stern. Two battleships stood by during the two hours it took for the former Blue Riband-champion to go to the bottom.

The Campania had avoided enemy attacks throughout the war, and had managed to escape the fate of among others the Lusitania and the Britannic. Her end had come through a sheer accident. Four days later, the First World War came to an end.

Specifications

- 622 feet (190 m) long

- 65 feet (19.9 m) wide

- 12,950 gross tons

- Ten-cylinder triple-expansion reciprocating engines turning two propellers

- 22 knot service speed

- Passenger capacity of 2,000 people