1889 – 1923

Also known as Paris and Philadelphia

During the 1880s, the evolution of the steamship was progressing at a rapid pace. The old remnants from the days of sail were beginning to disappear in favour of the new-style design of blunt bows and tier decks. On the North Atlantic the race was on, and the company who could boast with operating the Blue Riband-holder was guaranteed a lot of free publicity.

This was all very appealing to every shipping line working on the Atlantic route, and everyone wanted their share. The Inman Line, founded as the Liverpool & Philadelphia Steam Ship Company in 1850, was of course no exception. However, the company had had more than its share of misfortunes, financial and maritime, through the last years and the state of the company was poor. New ships were needed, but there was simply no way that the company could afford any newbuilds.

In 1886, the company was forced into voluntary liquidation, when it could no longer raise funds for unpaid debts. Yet rescue was not far away. The American financier Clement Acton Griscom, who already had under his ownership the Belgian company Red Star Line and the American Line, purchased the bankrupt Inman Line and made it the third separate subsidiary of his consortium International Navigation Company. The Inman Line was renamed Inman & International Line, and suddenly funds for new vessels were available.

The company now placed an order for two new ships from the shipyards of J. & G. Thomson, Glasgow. Not just any ships, though. The blueprints showed ships of unprecedented size, with the exception of Isambard Brunel’s Great Eastern of 1860. The lure of the Blue Riband had also affected the Inman & International Line, and so it had been decided that the two new ships would be built with great speed in mind.

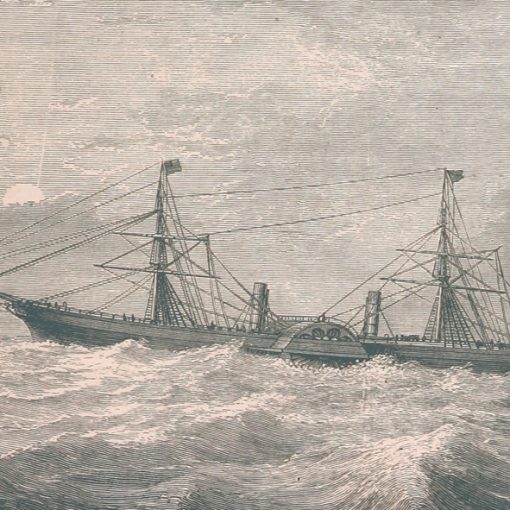

The first of the two ships (yard no. 240) was launched on March 15th 1888, and was named City of New York. A little more than seven months later, on October 20th, yard no. 241 left the slipway and was named City of Paris. Externally, these two ships might have appeared somewhat old-fashioned. Ships like the White Star’s first Oceanic had already introduced the blunt bow that would remain on steamships until the 1930s, but the two new Inman liners were constructed with clipper bows, complete with a graceful bowsprit. Amidships, three raked funnels stood tall and beautiful. The ships were fitted with three masts, ready to set sail if necessary, but that was merely an ultimate safety precaution. Earlier steamships had been constructed with a single propeller geared to their engines, and if something went wrong they had to rely on sails to take them to their destination. Propeller shafts snapping in mid-ocean was not very uncommon and without sails, ships would have been left drifting helplessly. But with the City of New York and City of Paris, an engineering novelty was introduced on the North Atlantic – twin screws. The risk of both shafts breaking was very low, and sails would never be used to any extent on these new ships. Actually, the very first ship with twin screws on the North Atlantic was the French Washington from 1864. Originally a paddle steamer, this ship was rebuilt with two propellers in 1868. However, the City of Paris and her older sister were the first ships originally built with this propulsion arrangement.

With highly efficient triple-expansion engines geared to their two propellers, the speed called for to conquer the Blue Riband would surely be achieved. But besides fast, these ships were also very safe. Their hulls were subdivided into 16 sections by 15 transverse bulkheads that rose 15 feet above the waterline. Below saloon deck, there were no openings – not even watertight doors – in the bulkheads.

In March of 1889, the City of Paris was finally completed. The following month, she set out on her maiden voyage, from Liverpool to New York. Although her engines worked flawlessly, it would take a little more time before she could capture the Blue Riband from the current champion – the Cunard Line’s Etruria. However, it is doubtful that the passengers exploring the new City of Paris cared much about the absence of a speed-record. The interior design of the two new Inman liners was indeed something extra. The First Class Dining Room could seat 420 people, and its ceiling was adorned by a glass dome. Furthermore, first class passengers could enjoy the comforts of the walnut-panelled smoking room or the library, complete with 800 volumes and stained-glass windows. For those who wanted a little privacy, the City of New York and City of Paris offered 14 private suites, with a bedroom and sitting room done in Victorian style. The comforts on the high seas were unquestionable, at least in first class.

Yet speed was still of great concern to the City of Paris’ owners, and by the summer of 1889, she was the record-holder in both eastbound and westbound directions, having crossed with an average speed of about 20 knots. However, in 1891, her westbound record was beaten by White Star’s Majestic. One year later, in 1892, she lost the eastbound honour to her sister, the City of New York. But that same year, she once more set a new westbound record, that would stand until 1893 and the arrival of Cunard’s Campania.

But in 1892, the British government withdrew their subsidies from the City of Paris and her sister. Griscom then found it best to transfer them within the International Navigation Company. His intention was to register them under the US flag, operated by the American Line, but there was one problem: an American law requiring American-flagged ships to be built in the United States. Griscom found a solution to this problem, by winning the grant of exception from Congress. In return, he promised to order for the American Line two new ships built at US shipyards. These subsequently became the St. Louis and the St. Paul. And so, the two Inman sisters were transferred to the American Line. The Inman trademark ‘City of’-prefix was removed, and the two vessels were renamed simply Paris and New York.

Within their new company, the Paris and New York operated on the New York-Southampton run. The Paris did so successfully until April 1898, when she was chartered by the US Navy for military use in the Spanish-American War. Renamed the USS Yale, she served as an auxiliary cruiser in the West Indies and later also as a transport. Although this military career did not last long, the Yale was involved in action a number of times. In Cuban waters, she was under fire a few times and responded in kind. Fortunately, she went through unscathed, and was returned to the American Line after five months of Navy service, in September 1898.

Given back the name Paris, the ship was returned to the company’s New York-Southampton route. In 1899, however, she was involved in a major mishap. Steaming in dense fog, a few hours out of Southampton, the Paris ran aground off the Manacles, Cornwall. The ship sprung a leak and was wedged between the rocks for three weeks. Compressed air was used to free the hull from water, allowing the holes to be cemented over. When made seaworthy, the Paris was towed to Belfast for reparations.

But the American Line decided that the Paris needed more than just reparations. While in Belfast, her three funnels were replaced with two taller ones, and her name was changed to Philadelphia. Shortly afterwards, her middle mast was also removed and with these changes, her appearance was changed dramatically. Returned to her owners, the Philadelphia was used on the Southampton-Cherbourg-New York service. She stayed on this route for a little more than a decade, but she was being outmatched fast by newer ships. While still fast and safe in comparison with other ships, the Philadelphia’s exterior and interior designs were now hopelessly outdated. So, in 1913, her first class accommodations were removed, and the ship was reassigned to the Liverpool-New York run.

Then, in 1914, the First World War erupted. The passenger traffic on the North Atlantic was changed dramatically as the large liners of the day were called in for military duties. Older ships like the Philadelphia were not as attractive for such use, and the old speed champion continued her commercial service. However, in 1918, the US Navy requisitioned her once again for military purposes. In this guise, she was renamed USS Harrisburg and was used to transport troops to Europe. During this last year of the war, she transported 30,000 troops and steamed 270,000 miles. Following the Armistice of 1919, she was used for repatriation work. Decommissioned in December of 1919, the old ship was returned to her owners and given back the name Philadelphia.

In 1920, the now aged Philadelphia was put on the New York-Plymouth-Cherbourg-Southampton run. However, the American Line did not have much interest in her, and in 1922 she was sold to the New York-Naples Steamship Co., her intended service being Gibraltar-Naples-Palermo-Piraeus-Constantinople. Within this company, she only made one voyage. She left New York with Constantinople as destination, but when the ship approached her first port-of-call – Naples – the ship was a floating problem. The company was facing heavy financial difficulties, and the crew had become mutinous. After an attempt to scuttle the ship had been made, the officers were forced to patrol the decks with revolvers drawn.

Upon the ship’s arrival in Naples, the authorities came on board and arrested the crew. The abandoned ship was left alone, and it eventually drifted ashore. Subsequently, she was sold for scrap. In 1923, she was towed to Genoa where she was broken up.

Specifications

- 560 feet (170.8 m) long

- 63 feet (19.2 m) wide

- 10,499 gross tons as originally built, 10,786 gross tons when rebuilt as the Philadelphia

- Steam triple expansion engines turning two propellers

- 20 knot service speed

- Passenger capacity of 1,740 people as originally built, 1,265 people when rebuilt as the Philadelphia