1905 – 1932

When the 20th century arrived, Great Britain was no longer dominant on the seas. Germany had introduced their superliner Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse in 1897, and it had taken the Blue Riband from Cunard’s Lucania almost instantly. Other German ships had followed in the Kaiser’s wake, and the Blue Riband was in 1905 held by two new German ships: Norddeutscher Lloyd’s Kaiser Wilhelm II had the eastbound record and the HAPAG-liner Deutschland possessed the westbound record.

However, Cunard was already planning their comeback. They had cleared a low-interest loan with the British government in aid to build two new ships which would be the biggest, most luxurious and above all fastest ships ever constructed – Lusitania and Mauretania. To easily take the Blue Riband back, Cunard’s new duo would need to maintain a service speed of at least 24.5 knots. As these two giants were of unprecedented dimensions, it was not certain that the standard reciprocating engines would be able to provide them with enough power to achieve that high speed. Cunard was already considering the use of turbine engines in their new duo, but as such engines had never been tested in ships of this size before, Cunard needed to make some sort of test before reaching a final decision.

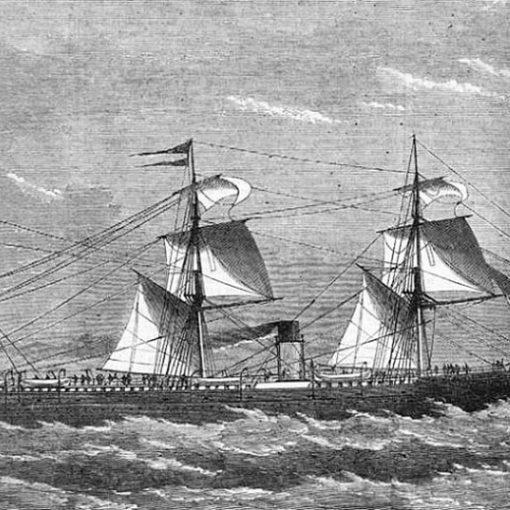

The answer lay in building two new ships. These would be identical, except when it came to their engines. One would be fitted with engines of the traditional reciprocation type turning two screws, and the other with modern turbines turning three propellers. Both ships were commissioned from the Clydebank firm of John Brown & Co. Ltd., so that they would be as much alike as possible. The first of the two vessels to go down the ways was the ‘old-fashioned’ one. Launched on July 13th 1904, the new ship was christened Caronia by Mrs. Choate, the wife of United States’ ambassador in London. At 19,524 tons, she was the biggest Cunarder built so far. The ship’s design differed from earlier Cunarders, and so her funnels were divided into four equal areas instead of five. The top quarter of the funnel was painted black and the rest was red separated by two thin, black lines.

As she was the biggest ship so far to enter the Cunard fleet, the new Caronia was of course put on the Liverpool-New York run. She was no record-breaker, Cunard saved that for the Lusitania and Mauretania. Still, the Caronia could maintain a service speed of 18 knots, making her average crossing time quite acceptable.

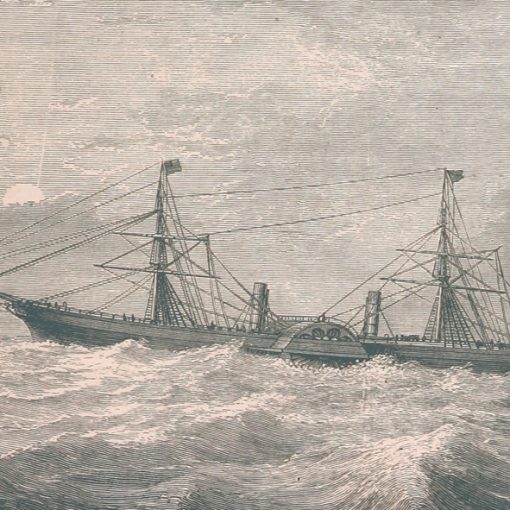

On February 25th 1905, the Caronia left her Liverpool pier for her maiden voyage to New York. The voyage was uneventful, but still a success. But on her third voyage, the Caronia was stranded off Sandy Hook. Fortunately, there was no real damage to the ship, besides the unfortunate delay. But Cunard still had reasons to rejoice, since the turbine-fitted Carmania had been launched four days earlier, on February 21st. However, the question of whether her turbine engines would be up to the test or not, would not be answered until the end of the year when the Carmania was to make her debut on the North Atlantic.

On December 2nd 1905, the Carmania set out on her Liverpool to New York maiden voyage. Her trials had created great expectations as she had easily exceeded her sister’s top speed with no less than two knots. The success was immediate. The Carmania proved to be both faster and more economical than Caronia, and the question of the Lusitania’s and Mauretania’s engines had now been answered – they would both be powered by turbines.

The Caronia could of course not be fitted with turbines after this revelation; the conversion would have been too complicated and expensive. Still, her quadruple-expansion engines were performing nicely, and there was no reason to change her service. She was kept on her New York route, and served it flawlessly until the event of the First World War. Like so many other liners of her time, the Caronia had been constructed so that she might be converted into an armed merchant cruiser in the event of war. When the first shots of World War I were fired, the Caronia was brought to Liverpool for conversion into a cruiser. The work was finished on August 8th 1914, and the Royal Navy requisitioned the ship.

On her third day of war duties, the converted Caronia intercepted and captured the German barque Odessa. The ship was then transferred to Halifax from where she worked the following six months patrolling the waters outside New York harbour. Caronia carried out this task suffering only one accident when she collided with the six-masted schooner Edward B. Winslow. Luckily, no one was killed in the collision and the two vessels were only slightly damaged. In May 1915, the Caronia returned to Liverpool for a complete overhaul. She then served as a contraband ship before she was returned to Cunard on August 7th, 1916. She was given a refit, but only to be requisitioned by the British government when it was completed. She served as a troop transport between Halifax and Liverpool for the duration of the war. When peace was finally achieved in 1918, the Caronia was kept on to return Canadian soldiers to their home country.

On September 12th 1919, the Caronia made her first post-war crossing between London and Halifax. She was given a reconditioning in 1920 and then continued to serve on the Canadian run in combination with her ordinary New York route. In 1926, Caronia went through another refit in which her passenger accommodations were reduced by 1,200. This was mainly to make her more suitable as a winter cruise-ship, a duty often given to older ships during the late 20s. The Caronia was sent on cruises between New York and Havana in the winter seasons, and remained on her New York run during the summer for the rest of her career.

When the 1930s arrived, the shipping companies of the world were suffering from the Depression set off by the Great Crash of 1929. The Caronia and her sister Carmania were now rather old ships, and they were both laid up at Sheerness at the end of 1931. In January 1932, the Caronia was sold to the shipbreakers of Hughes Bocklow & Co., who for some reason then resold her to a Japanese scrapping firm. The Caronia was renamed Taiseiyo Maru for her last voyage to Osaka, where she would be cut up. By the end of 1933, the Caronia was no more.

Specifications

- 678 feet (207.1 m) long

- 72 feet (22 m) wide

- 19,524 gross tons

- Steam quadruple-expansion reciprocating engines turning two propellers

- 18 knot service speed

- Passenger capacity of 2,650 people as originally built, reduced to 1,467 people during 1926 refit