1931 – 1940

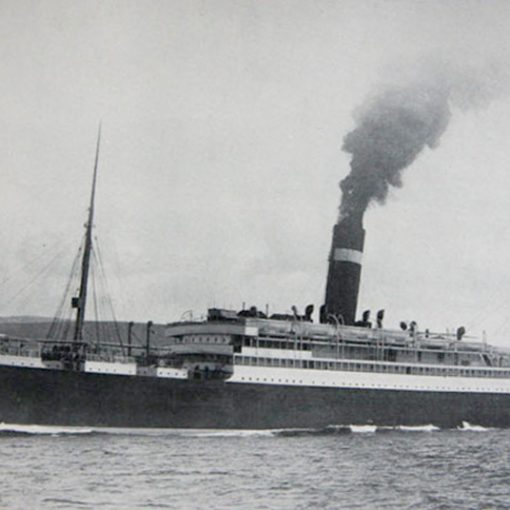

By the end of the 1920s, the Canadian Pacific Railway Co. was one of the foremost shipping companies on the North Atlantic. However, their services could not quite compare with those offered by other companies operating between Southampton and New York. Canadian Pacific did have ships known for their comfort and luxury, but the most fashionable ships were found on a route more southerly.

The battle for the passengers stood between many companies and the competition was hard. So, as an effort to lure some of the mid-Western and Western Americans to sail from Quebec instead of New York, the Canadian Pacific Line decided to place an order for a new vessel – a ship that would be the company’s largest to date. Canadian Pacific turned to the Clydebank shipbuilders of John Brown & Co. to create their new champion. Being a pioneering company in the already growing cruising-business, the company wanted the new ship to be built with dual-purpose in mind. She was to operate as an Atlantic liner in the summer season, and to go on lengthy luxury-cruises during the winter months.

On June 11th, 1930, the new ship was ready to take to the water for the very first time. It was indeed a great day for the company, with the new vessel being their largest ever. A great number of people had gathered, among them Edward, Prince of Wales, who was to do the actual christening of the new ship. Sending her to her rightful element, he gave her the name Empress of Britain.

Work soon began on fitting the new Empress out. As she was intended to attract passengers away from other ships, she was designed with a great deal of luxury – something that would also come in handy when she was to go on cruises. One of the most stunning public areas was the Mayfair Lounge, which was done in walnut complemented with designs of silver for the wall panelling. Inspired by ancient Greek architecture, the designers had included tall scagliola columns and pilasters. The ceiling was adorned by a large vault, which featured amber glass and the signs of the zodiac around the base. The Empress of Britain could also offer activities for those more athletically oriented. The first class gymnasium was equipped with a great range of devices, for example bicycling machines, electric horses and punch balls.

While carpenters and other craftsmen were working in the public areas with decorating the new Canadian Pacific vessel, engineers were busy installing the engines down below. The Empress was fitted with Curtis-Brown steam turbines geared to four propellers. These were expected to give her a service speed of around 24 knots. If so, she would be not only the largest ship on the Canadian run, but also the fastest.

When fitting out was completed, the Empress of Britain was finally ready for her sea trials. On April 13th1931, she set out to prove her worth. And so she did. By averaging a speed of 25.27 knots over the measured mile she showed her owners that she would not let them down, at least not when it came to speed. But would the passengers flock to the new Empress, as it had been hoped? Soon the company would find out.

On May 27th 1931, the day had come for the Empress of Britain to set out on her premiere voyage from Southampton to Quebec, calling at Cherbourg on the way. The departure was a festive event, being witnessed by among many others the Prince of Wales. This very first voyage of the Empress was a true success. Her time between Cherbourg and Father Point of 4 days, 19 hours and 35 minutes was the fastest ever. There was a new speed-champion on the Canadian route.

But what had seemed to be an enormous success at first soon turned out not to. The maiden voyage of the Empress of Britain had been an exciting novelty, but it did not take long before passengers started travelling on the trusted Southampton-New York route again. And to make matters even worse, the Depression soon created a massive downfall in the emigration to Canada. In 1932 there were only 6,882 emigrants landed in the country, compared with 133,141 in 1929. The Empress of Britain seemed to be facing hard times.

It was instead hoped that the Empress of Britain would make some profit with her winter cruises. On December 3rd 1931, she set out on her first world cruise. For her cruising duties, two of the ship’s turbines were shut down, as speed was not important on leisure cruises. Her two outer propellers were removed and stowed inboard to reduce drag, and thereby also bring down the fuel consumption.

The Empress of Britain’s world cruises were indeed something extra. Sailing from New York, she continued east through the Mediterranean and through the Suez Canal along to India, Java, Bali, China, Japan, the American West Coast and finally through the Panama Canal back to New York, and it was not cheap for a person to come along. The minimum fare was $2,100 and a whole suite could end up at an astonishing $16,000. Unfortunately, there were not so many that could afford these prices, and the Empress did not produce much profits as a cruise ship either, thus making her one of the least profitable liners of her time. Yet she would go on a world cruise every year until 1939, with the exception of 1933.

Nevertheless, the Empress of Britain continued serving Canadian Pacific in her dual role. In August 1934, she set a new eastbound record between Belle Isle and Cherbourg, completing the crossing in 4 days, 6 hours and 58 minutes. However, a year later, in June 1935, she was involved in her first major accident when during foggy weather she collided with the Common Bros vessel Kafiristan in the St Lawrence River. Three men who were working on the Kafiristan’s forecastle were killed in the impact, and several others were injured. The Canadian Pacific ship Beaverford was called in to take the Kafiristan in tow. The Empress was able to continue under her own power.

In contrast to this sad event in the career of the Empress of Britain, her proudest moment came in 1939. The British King George VI and Queen Elizabeth completed their goodwill-tour of North America in June, and the Empress was chartered to take them back to England. For the voyage, the royal couple and their entourage occupied a large number of the ship’s luxury suites. But only two and a half months after this joyous occasion, in Europe the sparks of war ignited what would become World War II. The Empress of Britain had left Southampton on September 2nd, and upon her arrival in Quebec she was ordered to stay there. On the 25th that same month, she was officially requisitioned to be used as a troop transport. Once she had been converted into such, she made two trooping crossings from Halifax to Clyde, each time escorted by destroyers.

In March 1940, the Empress was sent to Australia and New Zealand to transport troops to Europe. On May 12th she left Freemantle in a troop convoy together with the Empress of Canada, Queen Mary, Aquitania, Mauretania and Royal Mail’s Andes. In the autumn of 1940, the Empress of Britain was on trooping mission between England and Suez via the Cape. On her way back, she called at Cape Town. Leaving with 643 people on board, no one knew that this was to be her last voyage. On October 26th, when the Empress of Britain was off the West Coast of Ireland, she was suddenly attacked by a German long-range Focke-Wulf Condor aircraft. The ship was set on fire in the attack, and it did not take long before the crew had lost control of the raging blaze. The Captain ordered abandon ship, but a skeleton crew remained in an effort to save the ship.

The Polish destroyer Burza and the two tugs Marauder and Thames managed to take the burning vessel in tow, and headed for safe waters. But the German aircraft had reported the ship’s position via radio, and soon the German U-boat U-32 was on the Empress’ tails. The U-boat stalked its prey for almost 24 hours before, on October 28th, she was able to fire three torpedoes against the Empress of Britain. One of the torpedoes detonated prematurely, but the other two found its target, and mortally wounded her. The Empress of Britain went down, the casualties being counted to 49, most of whom had been killed in the air attack. Two days later, the U-32 was sunk by the destroyer Harvester.

Five years later, when the bloody conflict of World War II came to an end, no larger liner than the Empress of Britain had been sunk. She was the greatest passenger ship lost by the Allied forces during the entire war.

Specifications

- 760.6 feet (231.8 m) long

- 97.8 feet (29.8 m) wide

- 42,348 gross tons

- Four Curtis-Brown steam turbines turning four propellers

- 24 knot service speed

- Passenger capacity of 1,195 people

2 thoughts on “Empress of Britain (II)”

I’m looking for information on the Empress of Britain II. She landed in Montreal from Scotland on either July 28th or 29th, 1959. My wife, her sister and their mother were on board. I’d like to obtain a manifest showing their names as passengers. The information shown above depicts a 3 stack ship named the Empress of Britain II. All of the pictures that I’ve been able to find show the Empress of Britain having 3 stacks, but the Empress of Britain II only has 1 stack. Obviously I’m quite confused by this information. If anyone could assist my on this quest, I would greatly appreciate it. Rick.

Hello there Rick. The business with ships’ names can indeed be quite confusing, since names were often re-used when older vessels were replaced by new ones. The ship in this article was sunk during World War II, so as you understand it couldn’t have possibly landed in Montreal in 1959. You are most likely looking for this ship’s namesake, the third Empress of Britain, which was a post-war vessel which was launched in 1955 and entered service for the Canadian-Pacific fleet in 1956. Being a product of her time, she was fitted with a lone funnel, which matches your description.

While we haven’t published an article on this particular ship here at TGOL, you can go to the Wikipedia page at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/RMS_Empress_of_Britain_(1955) and use its references to hunt for further information. I hope this helps, and wish you good luck in your continued search. Thanks for stopping by our website!