1845 – Present Day

One of the greatest engineers of the 19th century was undoubtedly Isambard Kingdom Brunel. Employed as the head engineer of the Great Western Railway Co., Brunel had visions that not many could match. His idea of extending the company’s London-Bristol service with a steamer operating from Bristol to New York resulted in the world’s then greatest ship so far – the Great Western. The success of that ship prompted Brunel to realise more of his dreams. Great Western had been built with a wooden hull, but Brunel figured that being a stronger material, iron would allow for even larger ships. If the Great Western Railway Co. would have any hopes of winning a mail contract, they would need a few equally fast sister ships to the Great Western. But Brunel instead suggested that the company should build just one, really large ship.

Such revolutionary ideas were not always appealing to others, and it took some convincing from Brunel’s side before the company finally agreed to build the new ship. And so, in July of 1839, the first keel plates were laid down at Patterson’s shipbuilding yards in Bristol. Her intended name was Mammoth. As the ship grew in her construction dock, everything proceeded according to plans. Just as with the Great Western, the Mammoth would be constructed with conventional paddle wheels on her sides. But in May 1840, an event took place that made Brunel change his plans. At that time, the new experiment 237-ton vessel Archimedes arrived in Bristol to demonstrate her innovative propulsion system. She had been fitted with a screw-type propeller invented by Sir Francis Pettit Smith and Brunel, eager to examine her performance, chartered the Archimedes for private trials.

Brunel was fascinated with what he learned. The propeller appeared to be much more efficient than the traditional paddle wheels, and Brunel was so convinced of its superiority that he immediately changed the plans for his new ship – it would be fitted with a propeller instead. At about the same time, it was also decided that she would instead bear the name Great Britain.

The technological leap ahead with the Great Britain was large. Not only would she be the first iron-hulled ship ever, she would also be one of the absolute safest. Brunel had divided the ship’s hull into six compartments by equipping her with five watertight bulkheads. This division would be able to contain the rush of water, should the hull ever be breached. Furthermore, the Great Britain’s steam engine was of the very latest in design. Equipped with four 7-foot 4-inch cylinders, it was able to generate a steam pressure of 15lb/square inch, developing some 1,500 horsepower for the single, six-bladed propeller.

On July 19th 1843, the day of launch had finally arrived. His Royal Highness Prince Albert was present for the occasion. When the ship had been given its name, Mrs. Miles (the wife of one of the company directors) swung the bottle of champagne. Unfortunately, the bottle missed the bows and remained whole. Luckily, there was a spare bottle available, and the Prince showed better accuracy in his aiming when he made the second try. The construction dock was then flooded, and the Great Britain was floated out. A remarkable ship had been born.

However, the ship was still far from finished. The fitting out would take another two years, but the work that was done on the ship was fantastic. When finished, the Great Britain sported the most luxurious accommodations so far ever put to sea. Being the largest ship so far, the Great Britain had plenty of space to use for passenger areas. Matched by no other ship, she had cabins for as many as 350 passengers. The public areas had been done in the finest style, and the decorators had put mirrors to extensive use to enhance the impression of space. The main dining saloon on board was the most lavishly appointed afloat.

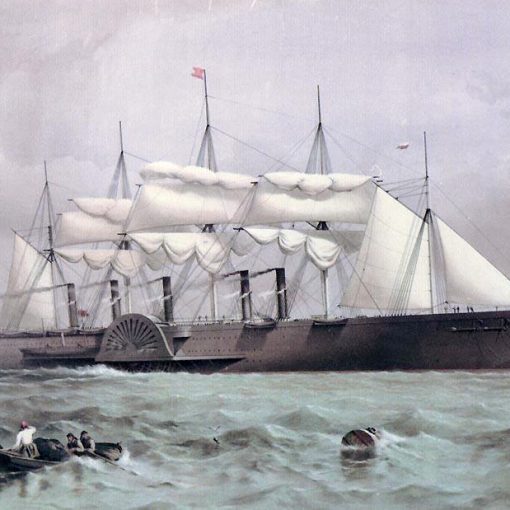

Finally, on July 26th 1845, the Great Britain set out on her maiden voyage from Liverpool to New York. Sporting six masts ready to set sail, she must have been a wonderful sight. Although the steam engine had evolved greatly, ships were still built with masts and sails as a safety precaution. After all, the machinery could malfunction!

Fifteen days later, she arrived safely in New York. For the first time in history, an iron-hulled and propeller-driven ship had crossed the North Atlantic. The Great Britain was a ship with many ‘firsts’, and this may have discouraged people at the start. In fact, only 50 passengers had occupied the cabins on her premiere voyage. Nevertheless, the Great Britain would soon prove her worth.

On September 15th, the Great Britain arrived back in Liverpool following her first eastbound passage. She had performed rather well, but had rolled more than anticipated. Brunel started to try and come up with a remedy, and in 1846 the ship was taken in to be fitted with bilge keels. Furthermore, her six-bladed propeller was replaced with a four-bladed one, and her masts were reduced to five. These changes were successful, and the ship’s rolling was decreased considerably.

The Great Britain continued to be successful, but in 1846 she suffered a major mishap. On September 22nd, she ran ashore on the rocky coast of Ireland at Dundrum Bay. The grounding was caused – it is said – by deviations in the ship’s compass caused by the iron of the hull. Unfortunately, the accident happened at the top of the spring tides, and it would take almost a year before there was another tide high enough to float her off.

Through the winter, the ship remained lying on the shore, battered by the cold gales. It was during this time that her iron hull showed its superiority to those made of wood. When the Great Britain was finally refloated on August 27th 1847, it was discovered that the hull had hardly been strained at all. The ship would be ready for service again within a short period of time.

But the accident had been serious in another respect. Her nearly year-long absence from the North Atlantic had caused large financial losses for the Great Western Railway Co. To deal with this situation, the company decided to sell the ship for £18,000 to Gibbs, Bright & Co. They decided to have the Great Britain refitted with a new, slightly less powerful set of engines and a lifting propeller. She was also re-rigged as a four-masted barque and fitted with two funnels instead of the original one. Retaining her name, the Great Britain was now intended for the Australian emigration run, and for this purpose her passengers accommodations were altered to 50 people in First Class and 680 in Third.

On August 21st 1852, she set out on her first voyage from Liverpool to Melbourne. The passage was long though, and the Great Britain could not store the required amount of coal in her bunkers. As a result, she had to stop for refueling at St. Helena. In spite of this, going to Australia on the Great Britain offered one of the fastest passages available. She averaged 120 days on a round-trip voyage.

But shortly after her debut on her new run, the Great Britain was taken in for yet another extensive refit in late 1852. Once again, a mast was removed and the ship was now fitted with only three masts. In addition, the funnels were reduced to the original single one. Following this refit, the ship returned to the Australian run, where she operated with success for the following three years.

In 1855, the British government requisitioned the Great Britain for military purposes. Along with a number of paddle steamers from Cunard and P&O, she was used for troop transports in the Crimean War. As so many times that would follow in the future, the merchant liners had been brought in to defend the British Empire. And they greatly contributed to the final outcome. After two years of government work, the Great Britain was returned to commercial service in 1857. She had now been transferred to the Liverpool and Australian Navigation Co.

What followed was another 20 years on the Australian run. The Great Britain did not see much action out of the ordinary, but one voyage was interrupted to claim the uninhabited island of St. Martin for the Empire. During the 20 years that passed, the liners of the world evolved swiftly and the Great Britain became more and more outdated with every year. In 1876, she was laid up after having completed 32 round-trip voyages to Australia. Awaiting a possible buyer, the ship’s future remained uncertain.

Four years later, in 1882, the ship was finally sold. Bought by Anthony Gibbs, Sons & Co., her new owners decided to remove the ship’s old engines and completely refit her as a three-masted windjammer. Curiously, it was also decided to cover the ship’s once innovative iron hull in wood. In stark contrast to her glory days as a passenger liner, the Great Britain was now employed as a pure cargo vessel, carrying Welsh coal and wheat to San Francisco around Cape Horn.

Yet this service would not last very long. In 1886, on only her third voyage, the ship encountered trouble in a storm off Cape Horn and had to seek refuge at Port Stanley on the Falkland Islands. When inspected, it was found that the ship had suffered considerable damage and her owners found it too expensive to repair her. Instead, she was sold to the Falklands Trading Company. The old Great Britain now faced her most disgraceful time, as she was converted into a floating coal and wool storage hulk. For the next 51 years she was used for this purpose, and was finally moved to the nearby Sparrow Cove on April 12th, 1937. Here she was scuttled and as the years went by, she slipped further into oblivion.

Astonishingly, this was not the end of the Great Britain. Fortunately, there were still those who appreciated her historic value. A recovery group was formed in 1968, and on April 12th 1970 – 33 years to the day after her scuttling in Sparrow Cove – the Great Britain was refloated by means of a submersible pontoon. Then the 8,000-mile journey back to Bristol could begin.

Two months later, the Great Britain was towed up the River Avon into Bristol. Some 100,000 people lined the riverbanks to welcome the old lady home. Upon the ship’s arrival in her home town, she was put into the very same dock where she had been built some 130 years ago. Restored to her original appearance, the Great Britain remains in Bristol to this day. A great monument of times gone by, the forerunner of all modern ocean liners remains every inch a stately and elegant lady into the 21st century.

Specifications

- 322 feet (98.4 m) long

- 50.6 feet (15.5 m) wide

- 3,270 gross tons

- Four-cylinder steam engine turning a single propeller

- 9 knot service speed

- Passenger capacity of 350 people (all in First Class) as originally built. Rebuilt with 50 in First and 680 in Third when refitted for the Australian run in 1850.