1838 – 1856

The early 19th century was a time of great technological advances. The industrial revolution had given the world the steam engine, and Man had not been late in taking advantage of its strength. Railroads stretched across the countries, suddenly making long distances quite easy to travel.

One of the largest British railway companies was the Great Western Railway Co. In 1837, they decided to extend their rail service to Bristol, and summoned the company’s board for a meeting. Here one of the directors complained that a railway between London and Bristol would be too long. The company’s head engineer, Isambard Kingdom Brunel, then replied that he thought it would be far too short. Instead, he suggested that the company should extend the line across the North Atlantic to New York by means of a new, large passenger steamship.

The idea was indeed radical but nevertheless, the board took the subject into consideration. Following discussions and economic calculations, they approved and gave Brunel permission to go ahead and build a ship for them.

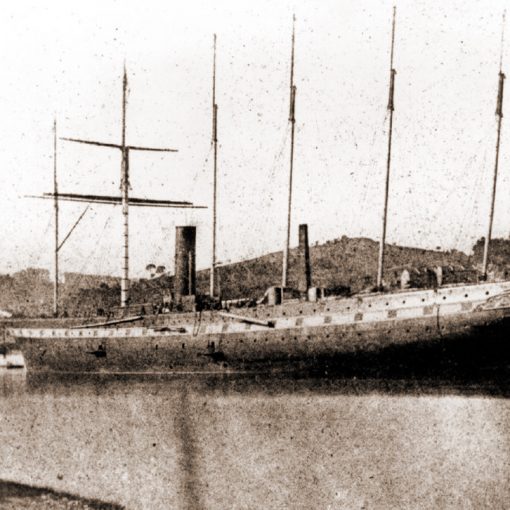

The ship was constructed in the shipyards of William Patterson, Bristol. As the very first purpose-built transatlantic steamer, she would be the largest ship ever so far. Constructed with a wooden hull, the new ship would be built with paddle wheels as means of propulsion. The propeller’s superiority had yet to be proven.

On July 19th 1837, the new ship was launched and christened Great Western amidst great ceremony. When afloat, the ship was towed to London to have her engines, which had been built by Maudslay, Sons & Field, installed. Although she was the first ship built specifically for the North Atlantic run, she already had a rival.

When the plans of the Great Western Railway Co. became known, another company decided to give them a match. Backed by the American businessman Junius Smith, the British & American Steam Navigation Co. set out on constructing a transatlantic liner of their own – the Royal Victoria. But, its construction was plagued by delays and it was soon apparent to her owners that their ship would not be completed in time.

But they still wanted to beat their rivals. So, instead of waiting for the Royal Victoria, they chartered the steamer Sirius to do the job. She was in fact a 700-ton coastal steamer, ordinarily employed on a service between London and Cork. Now she would set out to cross the Atlantic Ocean.

The two companies finished final preparations, and soon the actual race could begin. On March 29th 1838, the Sirius left London for New York. She would make a brief stopover at Queenstown to take on passengers, mail and as much coal as she could possibly carry. The ship was not built for ocean service, and would require great amounts of coal to finish the journey under steam. When the Sirius steamed out of Queenstown on April 4th, every space available below was used to store coal and she even carried two large heaps of it up on deck. As she reached open waters, she had a head start of the Great Western, but would it be enough?

The Great Western was at the time still tied up in Bristol, with final preparations being made for the forthcoming crossing. Four days later, on April 8th and with only seven passengers on board, she finally slipped her moorings and started the race to catch up with the Sirius.

On board the Sirius, the crew was aware that their rival had a far more powerful engine plant, and in order to reach New York first, they had to keep up the steam until the very end. In mid-Atlantic, the Sirius encountered a storm that slowed her down and increased the engine’s consumption of coal. As a result, she ran out of coal before reaching her destination. Still eager to win the race though, the crew now scavenged the ship for auxiliary fuel. Furniture, doors and even the ship’s emergency mast were used to feed the furnace. With sparks and smoke belching from her single stack, the Sirius arrived in New York harbour on April 22nd. The first Atlantic crossing made entirely under steam had been made, and history with it. But what of the Great Western?

She arrived in New York only four hours after the Sirius. The Sirius had reached New York first, but the Great Western’s crossing time – 14 days and 12 hours – was four days faster than her rival’s. The race for the Blue Riband was now underway, and would go on for more than a century.

Most important of all though, was the fact that the Great Western still had 200 tons of coal to spare when she reached New York. Brunel had proven to the world that, with the proper coal storage space, the new, large steamers could very well be employed on a regular transatlantic service.

The size of the Great Western did not only allow for more bunker space, but also more space for the passengers. Capable of carrying 148 people, the ship offered the finest amenities afloat so far. Her grand saloon was the most beautiful seen on the high seas, adorned by wall-panel paintings in the Watteau style. To summon a steward, all a passenger had to do was to pull a bell-rope. Luxury was indeed working its way onto the ocean liners.

Following her successful maiden voyage, the Great Western continued her regular service across the North Atlantic. The next year, she was surpassed as the largest ship in the world when the British & American Steam Navigation Co. liner Royal Victoria – by now renamed the British Queen – was finally finished. Great Western kept the Blue Riband though, and would not lose it until the arrival of Cunard’s Britannia in 1840. In 1842, the Great Western was transferred to the Liverpool-New York run. But to secure the success, the company would probably have needed to build some equal sister ships to the Great Western.

This did not happen, as Brunel and the company instead decided to build a new giant ship – the Great Britain. After having made 64 crossings, the Great Western was laid up in late 1846. The following year, she was sold to the Royal Mail Steam Packet Co. She served her new company during nine, rather uneventful years. In 1855, the Great Western was requisitioned by the British government for military use. Along with the Great Britain and a number of Cunard and P&O paddle steamers, she was used as a troop transport in the Crimean War.

Upon her return to commercial service, her owners no longer had much interest in her. Instead, the 18-year old ship was sold for scrap in late 1856. Her last trip was to Vauxhall, London, where she was subsequently cut up.

Specifications

- 212 feet (64.8 m) long

- 35.3 feet (10.8 m) wide

- 1,340 gross tons

- Steam engine turning two paddle wheels

- 9 knot service speed

- Passenger capacity of 148 people