1909 – 1917

When the Cunard Line had launched their giant duo consisting of Lusitania and Mauretania in 1906, they had used turbine power to drive the ships. This was a new power resource, and the conservative British could not easily be persuaded into this novelty. Even more conservative than Cunard was the White Star Line, who had preferred triple or quadruple expansion engines instead of the much better turbine engines on the Big Four quartet. The speed performance on this class of liners proved to be painfully slow. With a service speed of near ten knots better than the Big Four-quartet’s, Lusitania and Mauretania had showed the world the future power resource.

However, the White Star Line was not totally blind, and before ordering the first of the Olympic-class in 1908, the company would test what engines to be used on the Olympic and her future sisters. Two choices was to pick from; the first being the old and reliable expansion engines with two propellers. The second was a new combined version with the expansion engines’ exhaust steam used to power a low pressure turbine to drive a third propeller.

In 1907, the Dominion Line had laid down a vessel at Harland and Wolff, which they intended to name Alberta. This vessel’s engines were already finished, and they were of the same type that White Star was interested to find out more about; triple expansion engines with a low pressure turbine.

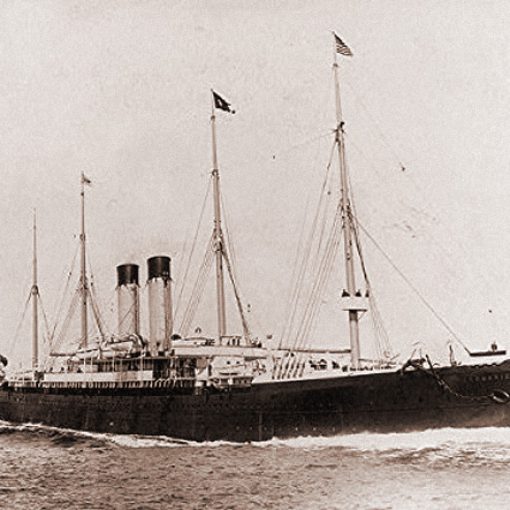

The White Star Line purchased this liner later that year and renamed her Laurentic. On September 9, 1908, the Laurentic was launched. She was intended to sail on the White Star Line’s Canadian-Pacific service, and became the largest vessel on this route.

Now that White Star had this type of vessel they needed an identical sister with the old type of engines to compare her with. Fortunately, the Dominion Line had a sister for the intended Alberta on the stocks. She was the Albany with twin screws powered by two quadruple expansion engines. She, just as the Laurentic, was purchased by White Star and renamed. Her new name became Megantic, and together with Laurentic she was intended to sail as the largest pair of vessels on the Canadian-Pacific route.

The Laurentic’s maiden voyage started off from Liverpool to Montreal via Quebec on April 29, 1909. As all other ships of her time, Laurentic had three classes one could travel in. The vessel had the same basic luxury as the large ships of the age, but in a smaller scale. Laurentic was equipped with a first class reading room, a smoking room with a partly glassed ceiling for the sun to shine through. If one had not got the money to travel in the prestige liners, but still wanted luxury, the Laurentic was the perfect choice.

After both the Laurentic and the Megantic had been tested against each other, the Laurentic proved to be the faster and more economic ship. However, the Megantic was not refitted with new engines; that would take too much work and time – and of course money – for such a small liner. The Megantic kept on sailing anyway, and never lacked in popularity or reliability. Neither did the Laurentic, and in 1911, she took the record for the Canadian route with a voyage-back-and-forth time of only thirteen days and four hours.

In the First World War, Laurentic was commissioned as a Canadian Expeditionary Force Troop Transport suited for 1,800 soldiers. In October 1914, she left Canada with the famed 32-troopship convoy that all together carried 35,000 Canadian troops to Europe. After completing her trooping duties admirably, the Laurentic was turned into an Armed Merchant Cruiser in 1915.

On January 25, 1917, the Laurentic steamed out from Liverpool. She carried 475 officers and crew, and a very distinguished cargo of gold bullion, worth five million pounds. The gold was being shipped to the United States in order to pay for war munitions supplied by the Americans. The ship had sailed a bit from the British coast, when a violent blast, followed by a second one was heard. Without doubt a torpedo or mine was in question. Unfortunately, the second explosion had destroyed the area where the engine room was. All of the ship’s lights had been put out, and the engines had been made useless. The Laurentic was doomed, and it was not made any easier by the fact that it was still dark, and the officers had to swing the lifeboats out in pitch darkness. Perhaps the pumps would have saved the vessel, but as all engineering personnel had been killed and the engine room was being water-filled rapidly, they could not be used. The Laurentic’s commanding officer, Captain Reginald A. Norton together with the ship’s chief steward, Mr. Charles Porter, descended down the vessel’s decks, which were being water-filled one by one rapidly. They managed to close two watertight doors, and see to that no man still alive was left on the sinking liner. After doing this they got up on deck and entered the last lifeboat. Then the Laurentic made her final plunge and sank in 125 feet of water.

The lifeboats had left the ship safely, but not the men inside them. Several of them had been badly hurt by the cold water, and as the lifeboats were picked up the following day, many were found dead in the boats.

The loss of the expensive cargo was also a major stroke for the British authorities. However, hope was that the cargo could be easily salvaged in the summertime, because of the shallow waters. The work started off as soon as it could, and after seven years of salvaging, 3,186 gold bars had been recovered. As the total number was 3,211, and no more could be found, the work was considered finished. In 1932, a private group of salvagers managed to pick up another five bars from the wreck. The remaining twenty bars still await recovery.

Specifications

- 565 feet (172.6 m) long

- 67.3 feet (20.6 m) wide

- 14,892 gross tons

- Two four-cylinder triple-expansion engines turning the two wing-propellers and one low-pressure turbine, powered by the expansion engine’s exhaust steam, turning the centre propeller

- 17 knot service speed

- Passenger capacity of 1,660 people