1960 – 2005

Looking back at the 20th century, the 1940s must be the one filled with most contrasts. The first half, from 1940 to 1945, was a time of great conflict, with the Second World War raging across the globe. This was a war of total destruction, and when peace was finally achieved in 1945, the tolls had been catastrophic. In terms of human lives, millions had perished, either in battle or through the cruelties of concentration camps. Materially, both sides had suffered immensely. Entire nations in Europe had been furiously bombed, and were by now severely crippled.

On the maritime side, things were not much better. A great number of merchant ships had been lost in the war, falling victims to torpedoes, bombs, mines or even scuttled by their own crews. Now that the world was ready to rebuild, ships were needed to get the commerce up and running again. But with resources close to depleted and a massive labour shortage, building new tonnage was easier said than done.

Fortunately, there was help available. During the second half of the decade, with the aid of the Marshall-plan, Europe was able to turn destruction into recuperation and rise to its feet again. With prospects of better times to come, the shipping companies now started looking into the possibility of commissioning new ships. One of these companies was Britain’s Orient Line, which was one of the dominants on the Australasian run. Starting in 1948, Orient Line put three new 28,000-ton ships into service over a period of six years. The Orcades came first, followed by Oronsay in 1951 and the trio was completed with the Orsova in 1954. These ships were clearly built for the post-war world, since their passenger accommodation was divided into two classes only; First and Tourist. They also sported a very modern appearance, with a single funnel perched atop a stepped-up superstructure. The novelties were taken one step further with the third ship – Orsova– which became the first major liner to dispense with the traditional mast entirely. All necessary rigging was instead attached to the funnel.

So, in the 1950s, this trio headed the Orient Line fleet, which also included some older World War II survivors like the Orontes of 1929 and the Orion, which had entered service back in 1935. And the future looked promising, indeed. While the more glamorous North Atlantic service was being subjected to the grim aeroplane competition, the Australasian route was booming. The reason to this was emigration, just as it once had been on the transatlantic run.

While things had certainly improved in Europe since the armistice, there were still millions of Europeans who were tired of the post-war austerity. So, just like many of their countrymen before them, they were now seeking a new life in a new country. But the United States were no longer the most common destination. Now, Canada, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand became the popular destination. Australia, which saw the opportunity to increase its population, even went as far as to introducing a unique government-assisted passage scheme. For just £10, one could purchase a ticket to a new life and a fresh start. But to get there, you had to travel halfway around the world.

And so, in the mid-1950s, with these prospects in mind, the Orient Line began planning for a new ship for their Britain-Australia run. However, there were many questions to be answered about the specifications of the future liner. The main issue was if they should go for a fourth sister of the Orcades-class, or set out to build something larger and faster.

It was not an easy decision to make. Orient Line approached the Barrow shipbuilding yards of Vickers-Armstrongs and asked them to investigate the matter, and after having gone over the aspects of fuel consumption, maintenance, staff costs etc, it became apparent that a large and fast ship was the best option. By offering a faster round trip, the ship would in it self make up for the higher costs of operating such a large and fast vessel. With the decision made, a contract was signed with the Barrow yard to build the new liner. A further two years was spent pondering and refining the blueprints, until the first keel plate on the yard’s number 1061 was laid on September 18th 1957. With work now underway, it would still take more than two years before the new liner could be launched.

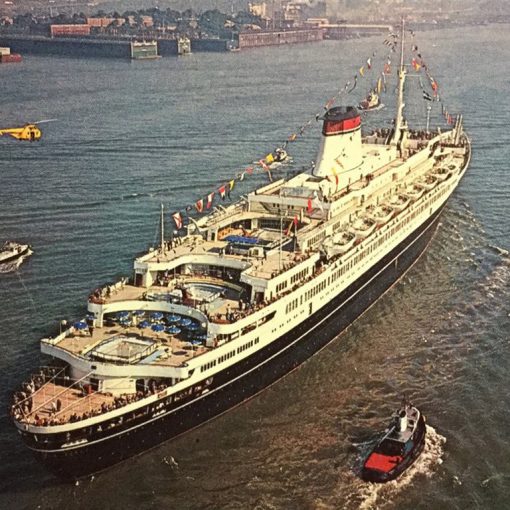

Then, on November 3rd 1959, the day of launch had finally arrived. It was a festive occasion, since this was the yard’s largest ship ever and, at the time, the largest yet built in England. Her Royal Highness Princess Alexandra had agreed to christen the new liner, and by pulling a handle she released the bottle of champagne which then crashed onto the ship’s bows. The name she gave the new liner – Oriana – was a name with many meanings. For one thing, it was a reference to the Elizabethan name used for Queen Elizabeth I who was in poetry called ‘Gloriana’. There was also the derivation of the name, which in ancient Greek means ‘East’ and in Latin ‘Dawn’. Then of course, it began with ‘O’ – conforming to the Orient Line’s traditional nomenclature.

When the classic ceremony had been performed, the massive hull started moving and slid down the ways into her proper element. The Orient Line house flag hoisted on her superstructure fluttered in the wind, and the powerful moment was accompanied by ‘Fanfare for Oriana’, specially composed for the occasion by Sir Benjamin Britten himself. Once the massive hull had been brought to a halt, it was then berthed at the fitting-out quay in Buccleuch Dock. Here, the still uncompleted Oriana would go through her metamorphosis to become a grand Orient liner.

As work progressed, Oriana came nearer to completion by the day. But as the ship’s appearance changed, so did circumstances around her. On May 2nd 1960, P&O and Orient Line went together and pooled their passenger ships in the same subsidiary company, which became known as the P&O-Orient Lines. It was however agreed that the two companies would retain their separate house flags and liveries. Indeed, P&O already owned a large share of the Orient Line, which it had obtained already in 1919.

Six months later, on November 13th 1960, the Oriana had been completed and was now to go through her sea trials. These were carried out on the Clyde, and were most satisfactory. Oriana had been built for speed, and her two sets of Pametrada geared turbines did not fail to deliver. In adverse weather conditions, the ship managed to reach a top speed of 30.64 knots. Since she had been designed for a service speed of 27.5 knots, these results were indeed pleasing to the company board. So, some five years after the original decision, Oriana was now finally ready to enter service as the new Orient Line flagship. After having taken on provisions, she left Southampton on her maiden voyage on December 3rd 1960, bound for Australia. This was a divergence for the Orient Line, whose ships had earlier sailed from London. The tradition was partially maintained though, as London was Oriana’s official port of registry, as could be read on her stern.

The port of Southampton had witnessed many maiden departures in its days, but surely none of such a peculiar-looking ship. Oriana had come out of the shipyard with a most unusual profile, and there were in fact a number of people who looked upon her as plain unattractive. Following the Orient Line trend set by the Orsova in 1954, she had no conventional mast but only a short radar mast. The bridge was situated almost amidships, crowning the welded aluminium superstructure’s series of terraced decks and the long, graceful bow. Her lifeboats were carried in special lifeboat bays in the hull, with several full-width decks above them. But the most odd feature must have been the two funnels. According to some, they looked like flowerpots stood upside-down. Differing slightly in design, the aft funnel was a dummy and was situated in a lower position than its forward counterpart. Oriana had also been built with bow and stern thrusters, making her more easy to manoeuvre.

But although there were many novelties that might have been hard to embrace at first, there were also many appealing features. Being an Orient liner, Oriana sported the wonderful corn-coloured hull of the company. The bow was adorned by a special bow decoration, consisting of two entwined ‘E’s’, representing two Elizabethan eras – the Tudor one after which she was named, and the Windsor one in which she was built. The ship’s name was spelled out in what must be some of the largest letters ever put on a ship and internally, she had been designed both for the Australian run as well as the growing cruise market. Her accommodation was divided into a First and a Tourist Class, with many comfortable public rooms at their disposal. The restaurants, the Princess Lounge, the Red Carpet Room and the Silver Grill to mention a few, they were all done in a typical 1950s style – elegant and functional, as opposed to gaudy and glitzy. In addition, every cabin was equipped with a radio – grand luxury in 1960!

Sailing via Suez, Oriana arrived at Melbourne for the first time on December 27th and in Sydney three days later, on the 30th. There she celebrated the New Year’s, and departed on January 5th 1961 from the new International Terminal at Circular Quay on a pleasure cruise to Auckland, Vancouver, some American West Coast ports and back to Southampton. During these premiere voyages, Oriana was warmly appreciated in spite of her unconventional looks. Upon her first visit to San Francisco on February 5th, the city council announced that the day henceforth would be known as Oriana Day.

She then set course back to Sydney, and was back in Southampton on March 25th 1961. Her owners could now summarise the successful maiden voyage. Not only was she the largest Orient liner ever, but she was also the largest ship operating in the Pacific Ocean. In addition, Oriana’s speed had certainly not disappointed. The passage from Southampton to Sydney via the Suez Canal had earlier been measured in about a month, but Oriana had completed the stretch in 21 days flat. The following June, she again set a new speed record when she sailed from Auckland to Sydney with an average speed of 27 knots – the fastest trans-Tasmanian sailing so far. In the month that followed, on July 31st 1961, she passed through the Panama Canal for the very first time on a return voyage to Southampton and again setting a record of sorts – she was the largest liner to transit the canal since Norddeutscher Lloyd’s Bremen in 1938.

However, in the midst of all this success, Oriana soon suffered her share of misfortune. On December 3rd 1962, while sailing in dense fog just off Long Beach, California, she collided with the veteran USS aircraft carrier Kearsarge. The Kearsarge’s aft starboard side was penetrated, resulting in a 25-foot gash. Oriana on the other hand, also received damages. A 20-foot hole was torn up near the bow, and a small fire broke out in her boiler room. This was quickly extinguished however, and luckily the incident did not result in any fatalities. When the damages had been assessed, Oriana was taken into Los Angeles for repairs.

The years that followed were much happier for the Oriana. On September 17th 1963, Sydney’s Mayor Henry Frederick Jensen presented the keys of the city to Oriana’s master during a ceremony held at Circular Quay. And being the speed queen that she was, Oriana set yet another speed record in 1964 when she completed the passage between Auckland and Sydney in 45 hours and 24 minutes at an average speed of 27.76 knots. But there were great changes waiting in the future. In 1965, P&O acquired the remaining shares of the Orient Line, and all the Orient ships were transferred to P&O registry. With this, Oriana lost her lovely corn colour, as she was repainted in P&O white. In October of 1966, the name P&O-Orient Lines was dropped, and restyled to just P&O. With that, the Orient Line passed into history.

Nevertheless, Oriana steamed on, still being a very stately lady. But in 1969, she again suffered bad luck when she was transiting the Panama Canal. While manoeuvring the ship through the tight locks of the canal, the ship struck the side of the basin and severely damaged one of her two propellers. Although repairs were carried out, it has been said that one of the ship’s drive shafts was so badly misaligned in the accident that she never again was able to reach her top speed of 30 knots.

The misfortunes seemed to continue into the next decade. In August of 1970, Oriana left Southampton on yet another routine voyage to Australia and New Zealand. But shortly afterwards, while the ship was still in Southampton waters, a fire broke out in the boiler room switchboard. The damage caused Oriana to lose all power, and had to be towed back into port. She now had to spend two weeks out of service while repairs were carried out, but at least the company could happily report that no one had been seriously injured in the fire.

When Oriana returned to service, her future deployment was not at all certain. As on the North Atlantic in the ‘50s and ‘60s, air traffic was now becoming a serious competitor on the Australasian route. It soon became apparent that Oriana, which had been built with occasional cruising in mind, soon would have to earn her living by doing pleasure cruises full-time. In 1973, her passenger accommodation was altered to cater for 1,677 passengers in one single class. From now on, Oriana’s deployment would be cruising, nine months out of Southampton and for three months from November based at Sydney, with positioning voyages via Panama in each direction.

Luckily, this did not mean bad times for Oriana. Since she was very much suitable for doing cruises, she continued to turn a profit in spite the fact that line voyages had been more or less abandoned. The task of cruising did not hinder the ship from seeing further dramatic events, though. In May of 1978, while Oriana was on a Caribbean cruise, the P&O headquarters received an anonymous letter when the ship was three days out of Southampton. The letter was an ominous one, warning that a bomb had been placed on board the ship. A bomb disposal squad was flown out to rendezvous with the ship, but upon their arrival a thorough search of the ship had revealed nothing. The whole thing was obviously just a hoax, and the bomb squad was never required to parachute on board.

A few years later, the Oriana’s long-time acquaintance with the port of Southampton ended in 1981, when she became permanently based at Sydney for South Pacific cruising. However, this service was only to last for another few years. In 1985, P&O announced that Oriana would be taken out of service and sold out of the fleet the following year. On March 27th 1986, she completed her final cruise for P&O and was then laid up at Sydney, awaiting her future. As a working ship, she had steamed 3,430,902 nautical miles and she had visited 108 ports over her illustrious career.

Two months later, on May 21st, the ship was sold to the Japanese company Daiwa House Sales. Their intention was to transform Oriana for use as a hotel, museum and leisure centre. One week after the sale, Oriana left Sydney bound for the Hitachi Zosen shipyard where she was to go through the conversion. Since she was to be used in a static role, the ship’s rudder and propellers were removed and placed on the fore deck by the old crew’s swimming pool. On August 1st 1986, Oriana was moored at Oita, near Beppu, a resort on the Japanese island of Kyushu. By now, her funnels had been painted pink and the ship had been secured to the wharf by means of welding. She would stay there for another nine years.

By mid-1995, the Daiwa House venture had collapsed, and the ship was sold to the Hangzhou Jiebai Group Co. Ltd., a Chinese department store operator. Oriana was loosened from her welded moorings and towed to Qinhuangdao in north China, where she was put to use as an accommodation centre and hotel. Sadly, she was not maintained very well, and soon fell into deep disrepair. In November of 1998, she was again sold, this time to the Hangzhou West Lake International Tourism Culture Development Co. Ltd., for the price of US$6,000,000. On November 15th, five tugboats towed Oriana from the port of Qinhuangdao to Shanghai.

As the ship was now in very poor condition, she was given an extensive overhaul, which included alarm systems, new elevators and climate control. It was announced that the ship would maintain “the traditional British style and elegance of its earlier years”. On February 16th 1999, the ship was once again opened to the public. After a US$3,630,000 refit, the ship included features such as hotel accommodation, a swimming pool, a miniature golf course, a 20,000 m2 exhibition hall and a wedding altar on the ship’s bow, inspired from the famous ‘bow-scene’ from James Cameron’s movie ‘Titanic’. At first, the project was highly successful, with a daily average of 3,000 visitors. Starting on December 24th, a nine-day millennium celebration was held on board, including theme dinners, symphony concerts, fashion shows, auctions, garden parties and buffets.

But this giant party turned out to be the peak just before a downhill. In July of 2000, it was reported that the liner had failed to generate the expected profits and she was shut down the following August. Once again, new owners were sought, and a public auction was held on September 28th. This time, the Song Dynasty Town Groups managed to acquire an 85% share of the ship for the price of US$7,250,000. They announced that the ship would once again be refurbished for static use, but many were, quite rightly, sceptical to those plans.

So from then on, Oriana sat in Shanghai, moored on the Huangpu River. During her time there, she was touted as the ‘Titanic of Huangpu River’, ‘the sister ship of Queen Elizabeth’, ‘a British Imperial Cruiser’ and ‘one of the four most famous luxury boats of the contemporary world’. Not much was recognisable from her glory days with the Orient Line and P&O, except for the bridge, which had not been altered much from its original layout. In many deck areas, the Asian climate had been hard on the old girl, where plywood planks have warped and crumbled. The ship’s library still remained more or less untouched, but unused and left to decay. The Lido Pool had been plated over, after having been utilised as a carp pond for a period of time.

But amazingly, her owners lived up to their promises, and showed that the thought of a refurbished Oriana was not just a pipe dream! Having been towed to the Chinese port of Dalian in the summer of 2002, the old ship went through a massive refit that transformed her into the main attraction of the Dalian Theme Park & Entertainment Center. Now boasting for instance a maritime museum and an 800-seat banquet hall & showroom, the Oriana quickly became a popular venue. Tours of the ship were offered, so that visitors could experience the engine room and the bridge first-hand. Things had really taken a turn for the better, but sadly, it was not to last. On June 16th, 2004, the Oriana was struck by a severe storm and was badly damaged. She took on a great deal of water due to her being holed at the bow, and as a result her lower decks were flooded, and the ship quickly took on a dangerous list to port. Attempts were made to right her and the owners even considered restoring her, but naturally the cost proved to be too great. And so, on May 13th 2005, the old Oriana departed and was towed to the Wayou scrap yard in Zhangiagang, China to be scrapped. Time had finally caught up with her, and just like so many other great ladies of the sea, she ended her days under the cutting-torch of the breakers, a sad shadow of what once was a magnificent vessel.

| Special thanks to Peter Knego and Alan Zamchick, who so kindly provided material for this article. |

Specifications

- 804 feet (245.6 m) long

- 97.1 feet (29.7 m) wide

- 41,915 gross tons

- Six Pametrada geared turbines turning two propellers

- 27.5 knot service speed

- Passenger capacity of 2,134 people

6 thoughts on “Oriana”

I am trying to find a record of a trip I did on Oriana for Christmas 2018/jan 2019 from Sydney, Australia around the Indian Ocean. We had NYE in Singapore. Thank you

Wrong Oriana, I’m afraid. If your voyage took place in 2018/2019, it must have been on the successor, MV Oriana, built in 1995. You seem to have sailed on her towards the very last stretch of her service with P&O. Soon after that, she was sold to a Chinese operator and renamed Piano Land. More info here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MV_Piano_Land

My dad crashed the Oriana in 1962

I was a cadet on Oriana back then. Peter Ballantyne

I have such fond memories of working there as a photog from 1974 on. It really was a very happy ship. both for crew and pax.

are there any pictures of the damage done to her starboard prop i was one of the two fitters that work on her in the dry dock in southampton

the tail shaft and prop was pulled out about 14ft and bent upwards we worked 21days none stop to do the repairs