1928 – 1965

Also known as Italia

In the 1920s, there was a great number of shipping companies operating on the lucrative North Atlantic run. One of the recent newcomers was the Swedish American Line (SAL), which had started its regular sailings with their first Stockholm, formerly the Holland-Amerika liner Potsdam, back in 1915. The company had actually been formed to profit on the great number of people emigrating to America, but by the time line was established, the great emigration wave was decreasing.

But, in the early 1920s, a few years of poor economic climate resulted in what was to be known as ‘the final wave’ of Swedish emigrants. And as Swedes naturally preferred to cross on Swedish ships with Swedish crews, the company was able to earn a small share of the mass migration to the New World. The line’s fleet grew when Canadian Pacific’s Virginian was purchased and renamed Drottningholm in 1920 and Holland-Amerika’s Noordam was chartered to sail under the name Kungsholm in 1923. The latter ship would however only serve the company for a year before she was returned to the Holland-Amerika Line.

As the Twenties neared its end, it was evident to the directors of SAL that the great emigration had ended. The Swedish American Line had by now instead established itself as a link between former emigrants and their old homeland and relatives who had stayed behind. But this traffic was not enough to earn the money needed, and so the company turned its attention towards the cruising business.

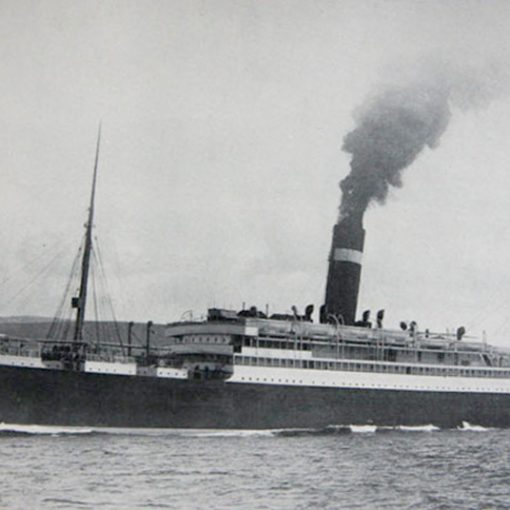

With these plans in mind, two new ships were ordered for the fleet in the late Twenties. The first of them was the Gripsholm, which was delivered from the Newcastle-upon-Tyne yards of Armstrong, Whitworth & Co. in 1925. She was in many ways a very innovative ship. Fitted with Diesel engines, the Gripsholm became the very first motor ship on the North Atlantic run. Equally notable, the Gripsholm’s interiors had been done in a fashion that would be suitable also for cruises. She was an immediate success, and this opted for yet another newbuild. This time, the order was placed at the shipyards of Blohm & Voss in Hamburg. And so, on March 17th 1928, the latest addition to the Swedish American Line’s fleet was launched and christened Kungsholm.

After seven months of fitting out and decoration, the new Kungsholm was ready to enter SAL service. She was a much anticipated liner, and the company directors were hoping for a new success. Like Gripsholm, Kungsholm was equipped with Burmeister & Wain Diesel engines, but in many ways she differed from her older running mate. For one thing, she was about 3,000 gross tons larger. Furthermore, her interior design was very unique. The company wanted the Kungsholm to be somewhat of a showcase for Sweden, and so contemporary Swedish art and architecture had been used to full extent in the ship’s decoration.

As a result, the Kungsholm emerged with public areas boasting rich colours, hardwoods, artistically worked metals and numerous paintings and artwork by renowned artists. She had also been designed with equality in mind. Although a three-class vessel on the North Atlantic, the interiors on Kungsholm could easily be unified as one for cruising purposes.

However, the ship got to a very auspicious start when on her sea trials in October an explosion occurred in the engine room and killed three men. Indeed, this was a tragedy, but repairs were quickly carried out to avoid any delays. And so, on November 24th 1928, Kungsholm set out from Göteborg on her maiden voyage to New York. By now, Gripsholm had already inaugurated SAL’s cruise program and Kungsholm was sent on her very first cruise – in the Caribbean – on January 19th, 1929.

The Swedish American Line’s reputation of offering splendid cruises was rapidly spreading, and it seemed as if this was the business of the future. With the financial situation growing worse by the day, more and more ships were taken off their regular North Atlantic run and sent off to do cheap cruises in warmer waters. The changing times were not least evident in 1932, when Kungsholm’s passenger accommodations were rebuilt and Second Class was re-labelled Tourist Class.

Kungsholm remained on the North Atlantic run during the 1930s, making cruises during the off-season. But in September 1939, the Second World War erupted in Europe, and suddenly the waters around the British Isles had been turned into a scene of great danger. To keep her out of harm’s way, the Kungsholm was instead employed making cruises out of New York. But, after a little more than two years of raging war in Europe, Japanese forces attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7th 1941, and thereby prompted the United States to enter the war on the side of the Allied forces.

Now, the need arose for a great number of troop ships to transport American forces to the battlefields across the globe. On December 12th, the Kungsholm was seized by the United States authorities for use as a troop transport. Less than a month later, on January 2nd, she was sold to the US War Shipping Administration and renamed John Ericsson. When she had been refitted with bunks and provisions for war duties, she entered service managed by the United States Lines. For the duration of the conflict, John Ericsson served as an American troopship in the Pacific Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea. She also participated in the invasion of Normandy on D-day, 1944.

When the war finally came to an end in 1945, John Ericsson was retained in American service for repatriation work. By 1947, these had been carried out and the ship was again available for peacetime passenger service. But she was no longer the ship that she once had been. When the Americans had converted her to a troopship in 1942, she had been practically plundered bare. In addition, in March of 1947 the ship was badly damaged by fire while in New York, thereby making her even more unattractive for passenger service.

In July 1947, the ship was bought back by the Swedish American Line. But the company no longer had any interest in operating her, so she was instead sold to Home Lines after only a few months. The ship’s new owners sent her to the Ansaldo shipyards of Genoa for a refit. Renamed Italia, she emerged on April 8th, 1948. Sporting the bright colours of the Home Lines, the Italia was now ready to start a new career. On July 27th 1948, she made her premiere voyage with the company from Genoa to South America. She remained on this run for about a year until 1949, when in June she was instead placed on the Genoa-New York route.

In 1952, the Italia was removed from the Mediterranean and was instead put on the Hamburg-New York run, with Hamburg-Amerika Line as managers. Two years later, she was involved in an accident. On October 6th 1954, whilst docking at Steubenhöft, Cuxhaven, the tug Fairplay 1 suddenly got caught under the Italia’s bow and was pushed underwater. The accident resulted in the loss of two lives.

Italia remained on the Hamburg-New York run as the 1950s neared its end. She was now pushing towards her 30th birthday, and was beginning to show signs of age. In 1958, the Italia was sent to the yards of Howaldt Hamburg to have her passenger accommodations refitted. When she returned to service in March of 1959, she was placed on the Hamburg-Quebec run with a capacity for 140 people in First Class and 1,150 people in Tourist Class.

In 1961, the Italia was once again re-deployed, this time to the New York-Nassau run. In addition, she was also used for cruises in the Caribbean. But by now the end of her career was approaching rapidly. In 1964 she was sold Freeport Bahama Enterprises. They renamed her Imperial Bahama, but as such she would never see passenger service. Instead, she was used as a floating hotel. However, not even this last task would last very long. The following year, she was sold for scrap. On September 8th 1965, the former Kungsholm arrived at Bilbao, where she would spend her dying days.

Specifications

- 609 feet (186.1 m) long

- 78.1 feet (23.9 m) wide

- 20,223 gross tons

- Burmeister & Wain diesels turning two propellers

- 17.5 knot service speed

- Passenger capacity of 1,575 people