1856 – 1872

During the mid-19th century, the Cunard Line was a young company. Its biggest rivals had not appeared yet, but competitors such as the American Collins Line gave them an arch-rival, for the time being. The Collins Line had quickly established their houseflag since the start of trans-Atlantic steamship business and was seen on the North Atlantic as one of the absolutely best and most reliable shipping companies. Ships such as Arctic and Pacific graced the waves of the North Atlantic, proudly sporting the Collins Line’s livery.

Cunard had started business in 1840 when they put the distinguished Blue Riband-taker Britannia in service. She was followed by three sisters. In 1843 the slightly larger Hibernia entered Cunard service. Just as the Britannia this ship only took the eastbound Blue Riband into possession. Hiberniaheld the title until 1849, and as Britannia and her sister Columbia still were fast ships, Cunard did not worry about losing the reputation they had of being the fastest shipping company on the North Atlantic. However, competition hardened and Cunard lost the Blue Riband to the American-based Collins Line in the early 1850s. Cunard had to do something.

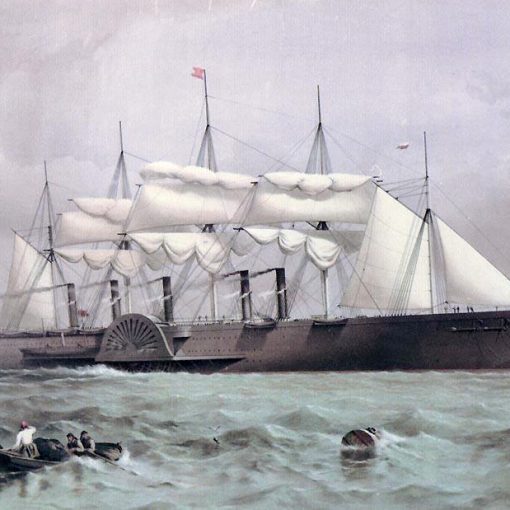

Ever since the pre-historic day when one of the early primates took a log, sat on it, and floated down the river, ships had been made from wood. The industrial revolution in Europe changed all this. The famous British engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel had proved with his Great Britain of 1845 that ships made of iron would float. When ocean going vessels now reached lengths of 300 feet or more, a stronger material than wood was needed to keep a ship’s hull together in one piece. Brunel had set the standard with the Great Britain of 1843. When Cunard needed a ship to compete with the Collins Line, they commissioned one made of iron from the Scottish shipbuilders Robert Napiers & Sons Ltd.

Taking the step from wood to iron must have been a gigantic step for the ultraconservative Cunard Line. Otherwise the ship would be very traditional – three sailing masts, a clipper bow and, of course, paddle wheels instead of the proven better screw, or propeller. As history would have it, this would be the Cunard Line’s second to last paddle wheeler. The last one was her close to identical sister ship that emerged shortly after her. By 1855, the new liner was nearing completion. She was launched and christened Persiaa few months before she set out on her maiden voyage from Liverpool to New York on January 26, 1856. Three months later she had captured the Blue Riband of the Atlantic for Cunard. As Persia was the largest vessel in the world at the time, Cunard had now totally surpassed the Collins Line.

If it was not for two very unfortunate events during the 1850s, the Collins Line might have continued its trans-Atlantic service for a much longer time. In 1854, their Arctic collided with a small French vessel who mortally wounded the larger ship. She sank with a heavy loss of life, including the company’s founder Edward Knight Collins’ wife and two of his children. In January 1856, another Collins liner – Pacific – disappeared without a trace never to be seen again until 1986 when a fisherman’s nets got tangled up in the wreck. Probably, the Pacific had encountered ice. When the Persia smashed into an iceberg the following month, she suffered serious damage to her starboard paddlebox. Luckily, she stayed afloat and managed to reach New York under sail. Following these indidents, the public’s faith in the Collins Line shrunk as the popularity of Cunard rose to heights never expected. The Collins Line was dead.

As late as 1863, the Persia lost the Blue Riband in both directions to her sister – the last paddle steamer Scotia. It would take more than twenty years before Cunard had the award in their hands again. In 1867 the Persia made her last trans-Atlantic crossing. Cunard thought her old-fashioned and aimed at newer and more modern liners. The following year she was sold, and had her engines removed. Then she spent the four coming years laid up, until she was sold for scrap at the age of 16. The handsome Persia was broken up on the River Thames in London in 1872.

Specifications

- 360 feet (110 m) long

- 45 feet (13.7 m) wide

- 3,414 gross tons

- Side lever engines geared to two paddle wheels

- 13.5 knot service speed

- Passenger capacity of 250 people