1922 – 1952

Also known as Admiral von Tirpitz, Tirpitz, and Empress of China (II)

When the Hamburg-Amerika Line, or HAPAG, put the Deutschland into service in 1900, it marked the beginning of the company’s managing director Albert Ballin’s quest to establish the line as the foremost in the world. The Deutschland soon proved her worth by conquering the coveted Blue Riband, but the glory was won with a costly lesson learned – such high speeds often meant reduced passenger comfort, due to vibrations in the ship’s structure. Albert Ballin realised this fact, and it did not take him long to decide that the Hamburg-Amerika would do just as the White Star Line had done in Britain already: give up speed and instead set the aim for size and luxury.

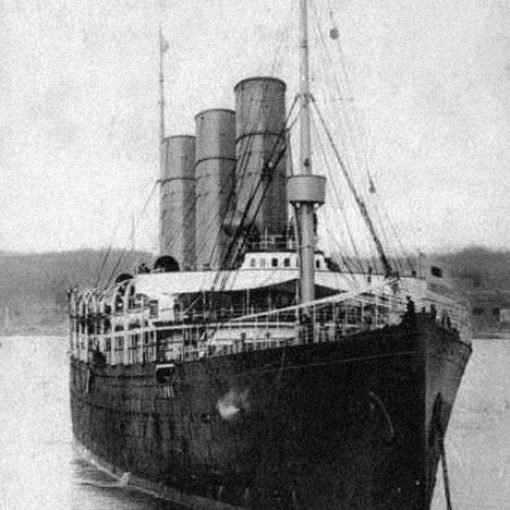

These plans truly became reality in 1913, when the first of three new mammoth liners entered service – the Imperator. At more than 52,000 tons, this ship exceeded even the White Star Line’s Olympic-class liners in size. Germany was indeed a powerful nation on the high seas. However, the Imperator and her two forthcoming sister ships were intended for the highly prestigious North Atlantic run. To cover more ground, Albert Ballin also commissioned some smaller liners for other trades, such as the route to South America. One of these ships was ordered from the Stettin-based Vulkan-shipyards. She was intended to serve as the company’s lead ship on the South American run, and upon her launch on December 20th 1913, she was given the name Admiral von Tirpitz. This choice of name was indeed an odd one, as Admiral von Tirpitz, who had done much to improve Germany’s navy, was a man with anti-British sentiments and views. Albert Ballin did not share these thoughts, and he feared that a war between the two nations might be at hand. Perhaps this was the reason why the ship’s name was shortened to just Tirpitz in February 1914.

The Tirpitz was designed to operate between Germany and the west coast of South America via the Panama Canal, which was soon to be completed. Constructed for emigrants in steerage, the ship was also fitted with many luxurious amenities in first class. As on the Imperator-class liners, the Tirpitz had her funnel uptakes split in two, run alongside the superstructure to rejoin at the base of the funnels. This arrangement left much space in the centre of the superstructure, thus making it possible for the ship’s decorators to give her spacious public areas.

The ship’s machinery was also of a new kind. She was fitted with turbines, but the problem with such were that they could only turn in one direction, thus making it necessary with a special reversed turbine for going astern. In addition to this, the quality of gear-cutting equipment was low and created a big problem for the ship’s engineers. To solve the problems with the gears, HAPAG decided to adopt a new German invention – hydraulic transformers instead of conventional mechanical gearing. This type of machinery had already been successfully used on the HAPAG 2,163-ton ferry Königin Luise, and it was hoped that it would perform equally well on the Tirpitz.

But where the new Tirpitz was grand on the inside with state-of-the-art machinery, her outward appearance left a little more to be desired. The proportions seemed off somehow, with a rather large superstructure and somewhat thin funnels. Also, an engine room access hatch amidships made the space between the second and third funnels 8 feet wider than between the first and the second. The gap could also be noted between the sixth and seventh lifeboats on each side. This asymmetry was indeed not at all pleasing to the eye.

Albert Ballin’s fears of a war were indeed justified, and later in 1914 they became a reality. With the shots in Sarajevo, the First World War was a fact. In Stettin, work was still being done on the Tirpitz when the news of war arrived. Work was immediately halted when it was clear that all shipyards had to deal with Navy orders. Later during the war, when the Germans felt confident of victory, work started to turn the Tirpitz into a Royal Yacht, aboard which the Kaiser intended to lead in the defeated British fleet. True, the Tirpitz would become a part of the British fleet, but not exactly in the way the Kaiser had planned…

In 1918, Great Britain and her allies stood victorious over the Kaiser’s Germany. The following year, the warlords converged at the castle of Versailles in France to dictate the peace agreements. These could be summed up in one word – ruthless. Germany was given the entire blame for the war, and was sentenced to give up all their ships as reparations for allied vessels sunk during the war. This of course included the Tirpitz, which was still lying at the Vulkan shipyards in Stettin, waiting for her future to come.

In March of 1919, the Tirpitz was officially handed over to the British, and she was to be completed in Hamburg. Work was soon under way, but was delayed when a fire broke out on board. The fire was easily extinguished, though, and work could soon continue to complete the now six year-old vessel. The ship was finally completed in November of 1920 and was sent to Hull, where she arrived with another former HAPAG-liner, namely the Kaiserin Auguste Victoria, who had also been given to the British. Her first task with her new owners was garrison troop replacements with P&O as managers. When she was finished with this mission, she was laid up at Immingham for a few months in wait of more work.

On July 25th 1921, the Tirpitz was acquired by the Canadian Pacific Railway Company and renamed Empress of China. The following months she was sent back to her original builders to have her engines converted to oil-burners. When this refit was completed, she was sent to the shipyards of John Brown & Co. to be fitted out according to Canadian Pacific requirements. Canadian Pacific’s intention was to use the former Tirpitz on their Pacific run between Vancouver and the Orient.

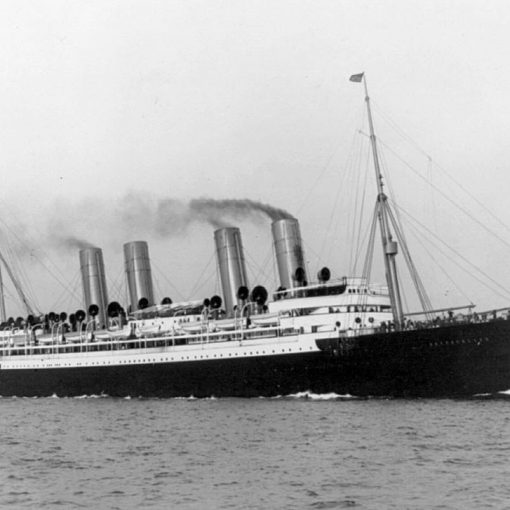

Finished by the summer of 1922, the ship was again renamed on June 2nd, this time to Empress of Australia. The refit had increased her size slightly, from her original 21,498 tons to 21,860. On June 16th she left the Clyde for Vancouver, from where she would finally start her commercial service, a little less than nine years after her launch! Painted black with a white band running along her hull, the Empress of Australia was ready for her pacific route.

On July 28th, the Empress of Australia set out on her maiden voyage, bound for Hong Kong and Yokohama. However, it soon became evident for the ship’s engineers that something was seriously wrong with her engines. The boilers were working inefficiently, and the ship could not reach her desired service speed, thereby putting her behind schedule. And as if this was not enough, one of the turbines was disabled at the start of her second voyage, forcing the ship to return to port. The Empress of Australia was sent off for repairs, and she was also fitted with new oil-burning boilers to replace the inefficient ones. This helped, but the ship was nevertheless still a big disappointment for Canadian Pacific.

But despite of all these problems, Canadian Pacific kept the Empress of Australia on her current run. One of the most dramatic events of her career occurred on September 1st 1923, when she was to leave Yokohama with about 2,000 people on board. Suddenly a violent earthquake struck, and the ship started swaying from side to side at the dockside. As an attempt to escape, the Empress of Australia started to back away from the pier, but got her propellers caught up in another ship’s anchor chains. The Empress was left unmanoeuvrable, but fortunately the 4,787-ton Dutch tanker Iris managed to tow her away from the danger. After a Japanese navy diver had removed the tangled anchor chain, the Empress headed back into the harbour to participate in the rescue work, saving more than 3,000 people with her boats. The ship’s commander, Captain Robinson, was subsequently given several honours for this heroic act.

After this dramatic event, the Empress of Australia remained on her usual route. However, her engines were still performing badly, and in May 1926, she was sent to the Fairfield Shipbuilding and Engineering Co. at Govan to go through a major re-engineering programme. The job would take ten months and £500,000 to complete, and involved the installation of a whole new set of Parson’s turbine-engines. The rearrangement of the boilers became a complicated matter. Canadian Pacific did not want to cut up the ship’s marvellous interiors, so the old boilers were cut up in the boiler rooms, and carried off the ship. The new boilers were then lowered into the forward hold, and hauled into position on skids through the opened up bulkheads.

After this technically challenging refit, the Empress of Australia was ready for service again in the summer of 1927. It did not take long before it was evident that the massive refit was just what the Empress needed. Her service speed was increased by more than three knots, making her able to operate easily at a 19-knot speed. In addition, Canadian Pacific was thrilled to learn that the ship’s fuel consumption had been reduced by almost a third. These factors, plus the fact that the Empress had wonderful interiors, made Canadian Pacific decide that she would be put to best use by serving two purposes, both as a trans-atlantic liner and a cruise ship.

The Empress of Australia’s first voyage since the refit commenced on June 25th, 1927. Leaving Southampton for Quebec, there were a couple of distinguished passengers on board, namely the Prince of Wales and Great Britain’s Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin, who were both on the way to the Diamond Jubilee celebrations of the Canadian Federation. This was the start of the Empress of Australia’s new service, as a trans-atlantic liner between Southampton and Quebec from spring to late autumn and then as a four-month world-cruise ship sailing from New York. In 1929 she was repainted white with a blue band along her hull.

Continuing to serve Canadian Pacific, the Empress of Australia managed to keep a reputation as a very beautiful and luxurious ship. In 1939, King George VI personally chose the Empress to be chartered as a royal yacht to carry him and Queen Elizabeth to Canada. Some of the ship’s cabins were converted into royal apartments, and the first class smoking room was turned into a private dining room for the royals. When finished with this honourable task, the Empress of Australia remained on her Southampton-Quebec run for another three months. However, in September 1939, yet another global conflict ignited in Europe.

The Empress of Australia was sent to Southampton where she was to be converted into a troopship. Painted in grey, fitted with a three-inch gun and with a carrying capacity of 5,000, the Empress left on her first wartime voyage to Ceylon and Bombay on September 28th, 1939. Following this task, the ship then went across the Atlantic to Halifax, from where she joined a large convoy carrying Canadian soldiers to the battlefields of Europe. During the entire war, the Empress of Australia enjoyed a very good luck, and was only seriously damaged once – when she was holed by the Orient Line’s 14,982-ton Ormonde during the North Africa campaign in January 1943.

In September 1945, after six years of military service, the Empress of Australia left Hong Kong with ex-prisoners-of-war and internees on her final wartime voyage. Upon her return to Liverpool, Canadian Pacific announced that they no longer had any interest in using the ship as a passenger liner, and so it was decided to charter her to the navy as a troopship. At the end of 1946, the Empress of Australia was sent to the Belfast shipyards of Harland & Wolff to be refitted as a full-time trooper. In this guise she operated mainly between Liverpool-Bombay or Liverpool-Port Said. In November 1950 she was also employed carrying military personnel to Pusan during the Korean War.

But by now the ship was old, and the Empress of Australia arrived at Liverpool for the last time on April 29th 1952 at the end of her 234th voyage. She was then sold for scrap to the British Iron & Steel Corporation (BISCO), and on May 8th 1952 the Empress of Australia sailed for Rosyth to be cut up. Of all the ships that had resulted from Albert Ballin’s grandiose plans more than 40 years ago, the Empress, or the former Tirpitz, was the one that had survived the longest time.

Specifications

- 589.8 feet (179.8 m) long

- 75.2 feet (22.9 m) wide

- Originally 21,498 gross tons, 21,860 gross tons after British refit

- Originally two steam turbines with Föttinger hydraulic gearing, 16,000 hp. Refitted with two Parson’s turbines in 1924, 20,440 hp. Two propellers.

- 16.5 knot service speed with original engines, 19.5 knots after engine refit

- Passenger capacity of 1,975 people

16 thoughts on “Empress of Australia (I)”

I travelled to Egypt on the Empress of Australia in 1949 with my mother and two brothers to join my father who was in the RAF. I have the menu dated Sunday January 30 1949 and my landing card.

My Dad, Dr Cornelius Kelly, was an officer on board The Empress in 1945 on its voyage from Liverpool to Hong Kong setting out to be part of Operation Downfall, before the Japaneese surrender.

On 10th January 1946 my mother and I ( I was just two and a half ) boarded The Empress of Australia in Liverpool. We were going to Singapore to be reunited with my father. The ship was due to sail at midnight but the dockers went on strike so we didn’t sail until the 13 th. There were huge storms in the Bay of Biscay but glorious weather in the Mediterranean. Whilst going through the Suez Canal we had to pull over to let the Ark Royal pass , unfortunately we had gone aground and had to be pulled free. Once out of the canal the ship stopped all movement and the first engineer, who had died, was buried at sea . Whilst we were in the Indian Ocean a crew member committed suicide and he was also buried at sea.

We moored off Ceylon and some local dignitaries were entertained on board. Shortly after this measles broke out and when we arrived at Singapore ambulances were waiting at the dockside to take the patients to isolation in hospital

I was on her last voyage to Singapore / Korea left Liverpool late December 1951 this was the time that

The USA freighter was listing badly I the English Channel and eventually sank with no loss of life.

My Canadian grandmother was the hairdresser on the ship and met my English grandfather, an engineer, onboard. Both were present during the 1923 Yokohama earthquake. I remember my grandmother telling me about how the ship was turned into a hospital and having to remain in the harbour for several weeks.

Further to Roy Williamson`s comment .I travelled on her in Sept 1946 from Liverpool to Hong Kong was this her last trip (I was only a child) I wonder if he was one of the troops who took me for a drink regularly? They bought me a lemonade and called it a `beer`. Result when I got to Hong Kong two of my fathers policemen took me out for a meal and brought me back drunk!

I travelled on her in Sept 1946 from Liverpool to Hong Kong was this her last trip (I was only a child)

I sailed on the empress of Australia in September of 1944. we were supposed to arrive at Cherbourg, France with the 9th armoed hq company, but had to alter convoy destinations on account of a possible German sub surprise. it was first crossing. my return trip to u.s. , I was transferred to the u.s.s. Uruguay

I have recently found crew lists for Emp of Aust. and they show the ship working between Liverpool & Glasgow going to New York & Boston during 1943-44. Any thoughts? Another ship with same name?

Hi Glynne.

My father was a crew member at this time. Sailed out of Liverpool 29.4.44 and returned to Glasgow 23.8.44.

Is it possible you could send me the list?

Thanking you.

Ken.

Travelled on this Empress, 1952, from Port Said home via Malta and Gibraltar after military service in the Middle East. Happy voyage after having served “abroad” for three and a half years. Happy memories.

I travelled on the Empress as a forces child returning from Egypt arriving dark dreak Liverpool in November!

I was a passenger on the ship around 1948 or 50 we travelled as civilian passengers between gib and Malta, I was only around 4 at the time but I remember a very rough voyage.. my mum and I were sharing a cabin with another mum an her child my brother aged 14 was billeted with the crew. If you can tell me anything I would be very happy to know of it.

I was on the Empress when she made her last trip from Liverpool it was a 45 day trip to Hong Kong. We slept in in hammocks on F deck. We left Liverpool with troops from a Tank brigade and the 32 Med regiment R.A. We ran aground in the Bitter lakes and needed help from a few tugs to free us.

Thank you for sharing your memories here, Mr Williamson! For someone like me, whose connection with the great ocean liners is mostly academic and almost abstract, it is wonderful to hear from people who actually walked the decks of these lovely vessels.

My late father-in-law recorded in his note books that he kept during his time on the navy and the merchant navy 1943 to 1949 that he was aboard Empress of Australia in 1947 passing Gibraltar on 13 December and arriving in Liverpool, UK on 16 December 1947 at 1.45pm. He was stoker so one of the people who would have been shovelling the coal into the boilers. His note ends “Distance 22,000 miles” so my guess is that maybe he boarded the ship in Liverpool for Australia and returned with her bringing troops back. Thank you for operating your web site. It is fantastic to be able to find out so much information about a ship he was on.