1850 – 1854

The first purpose-built ocean liner had been the Cunard pioneer steamer Britannia. She entered service in 1840 and proved to be somewhat of a success. She was one of the ships that helped prove that there were considerable amounts of money to fetch in passenger traffic across the North Atlantic. Previously, a shipping line’s profits had basically come from government contract and money gained from the cargo.

In 1845, the same year as Isambard Brunel’s fabulous Great Britain entered service, an American shipping company entered the business. It was the Collins Line, which had been founded by the American Edward Knight Collins. Before entering the risky North Atlantic passenger business, Collins had operated a successful sailing packet company. Many thought him a daredevil to enter this kind of business.

Collins realised it was a dangerous game that he had entered. To secure profit, he applied for a mail subsidy to the United States Congress. He mentioned the fact that the British were by far the dominant factor on the Atlantic, and it would be more than appropriate for an American company to challenge them. The Congress agreed with Collins and gave his line the subsidy. One of the conditions was that United States should be able to use the Collins Line ships in the event of war.

The first of the Collins Line’s Atlantic steamers entered service in early 1850. She was the Atlantic and would within short be followed by three running mates being the Pacific, Arctic and Baltic. When introduced on the high seas, these vessels were immediately recognised as the best liners available. They were faster, larger and more luxurious that their closest competitors – the Cunard liners. The Britannia was a mere 1,139 gross tons large and had a service speed of 9 knots, while the Collins Line ships were all in the vicinity of 2,800 tons and could maintain a service speed of 12 knots for an entire Atlantic crossing.

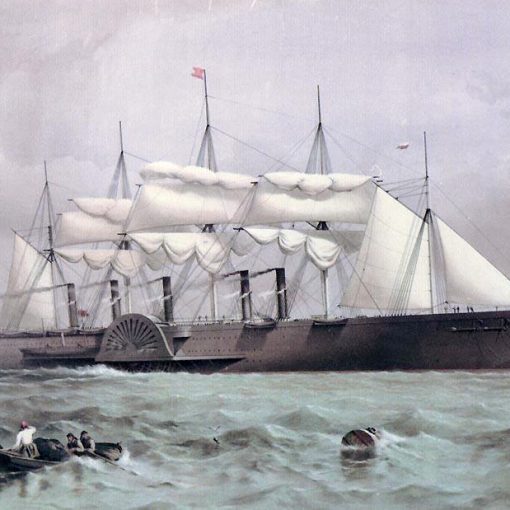

The Pacific entered service shortly after the Atlantic, and then the turn came to the third of the sisters. The Arctic had been launched on January 21, 1850 and her maiden voyage was on October 27, the same year. The exterior of the ship was of the classic style for the time – a wooden hull, single funnel, three masts and paddle wheels. However, she sported the novelty of a straight stem, which was quite unusual in the mid-19th century. The Arctic only had accommodation for 200 first class passengers. However, berths for additional eighty second class passengers were added in 1851.

The money Collins had invested in powerful machinery had certainly paid off, at least in prestige. Between 1850 and 1851, the Pacific had taken the Blue Riband in both directions from the Cunard Line’s Asia and Canada. But as Collins drove his ships at sometimes too high speeds, the company often had to pay large reparation costs for broken boilers and other machinery. Still, the Collins Line had established a brand on the North Atlantic and Cunard lost all too many passengers to the rival shipping line. The British company realised that in order for them to survive, they had to create even better ships than the Collins steamers. However, as the Collins Line seemed to be haunted with bad luck, Cunard could sit back within short and watch the income increase again.

But before the rotten luck struck the Collins Line, they had their sweet share of glory in February 1852 when the Arctic took the eastbound speed record with an average speed of 13.06 knots. She would keep that honour until long after she was gone.

The first major stroke for the Collins Line occurred on a chilly September day in 1854. On the 21st, the Arctic had left New York for another crossing to Europe. She carried 147 first class passengers, a full second class compliment and a crew of 135, ending up with 368 souls on board. Among the first class passengers were Collin’s wife and two of his children accompanied by members of Collin’s shipping partner James Brown’s family.

On the 27th, when the Arctic had reached a point about 60 miles south of Cap Race, she encountered dense fog. The policy for Collins liners was to race through an area of fog as quickly as possible in order to flee it. This foolishness resulted in that the Arctic was unable to turn in time when a small French iron-hulled steamer called Vesta came in her way. The collision was violent and as the Vesta’s metal structure turned the Arctic’s wooden hull into ribbons, the Collins liner began to sink.

The collision resulted in panic among the Vesta’s passengers. They thought she was more badly damaged than she actually was. The passengers and crew, numbering 197, immediately started to evacuate the Vestain favour of the Arctic. However, it was soon apparent which ship was the worst damaged, and the Vesta luckily made it into shore three days later.

As the passengers of the Arctic began to realise that their ship was sinking from under them, the panic soon developed among them. The water was rushing in through three holes below the Arctic’s waterline. The Arctic’s master, Captain Luce immediately ordered the head of his ship to be turned towards Cape Race, which was the closest point of land. But the speed of the ship further increased the inrush of water, and four hours later the water had reached the furnaces, making the voyage impossible to continue.

The weather conditions were not the best for the stricken Arctic and her passengers. It was blowing a strong gale at the time of the sinking, and some of the first boats to be launched were destroyed, requiring many lives. Other boats, which were launched successfully, were probably not manned or equipped enough – because they were never heard of again. A mere two boats with 31 crewmembers and fourteen passengers managed to reach Newfoundland. A raft made of wreckage supported 72 men and four women from the beginning, but the strong wind and the violent waves swept them off one after one until only one remained. This man was later saved by a passing ship.

Captain Luce had managed to escape the ship on a raft along with fifteen other persons, among them his own son. The young boy was unconscious and his father held him in his arms. At that time, the Arctic had entirely sunk beneath the surface. As the ship construction was made largely out of floatable wood, big pieces broke loose when the ship crashed onto the seabed and raced for the surface. A large section of the paddle wheel housing came up edge-wise, hitting the captain’s son in the head, who was killed immediately. Captain Luce had to let go of his son and start struggling for his own life. Among with approximately fifteen other men, he hung onto to the raft, but soon only three remained. After having seen several ships that had failed to spot them, they were picked up on the 29th by the Cambria bound to Montreal from Glasgow.

The conclusion of the disaster was devastating for the Collins Line. Panicked crewmen had not taken the time to inform and assist passengers, but left them on the ship. This resulted in that no women or no children were saved in the disaster. All three of the Collins family went down with the ship, along with five of the Brown family. Of the 368 originally on board approximately 300 had perished.

The Collins Line had further problems in 1856, when the Pacific just vanished during a trans-Atlantic crossing. She was not found until 1986 when a fisherman got his nets caught up in the wreck. Atlantic passengers no longer trusted the American Collins Line, but put their faith in the Cunard Line again. The Collins Line built a new and larger liner – the Adriatic – to compensate for the losses, but by the early 1860s the company went bankrupt.

The Arctic remains on the spot where she once sank, and to my knowledge no exploration of the wreck has been made.

Specifications

- 285 feet (87.1 m) long

- 45.9 feet (14 m) wide

- 2,856 gross tons

- Steam engines powering two paddle wheels

- 12 knot service speed

- Passenger capacity of 200 (later 280) people