1900 – 1947

Also known as Stockholm (I), Solglimt, and Sonderburg

The early decades of the 20th century were indeed prosperous times for the world’s shipping companies. A vast number of emigrants were leaving the homes in the Old World and set out to find a new life on the other side of the North Atlantic. Most of them came to the United States, where the unrestricted immigration laws welcomed anyone who was healthy and could earn their living in America.

This made the North Atlantic the most profitable shipping lane. The shipping lines were competing for popularity among the emigrants’, for it was in fact they who provided the real income. The steamship design had evolved rapidly, resulting in larger, faster and more luxurious vessels constantly surpassing each other. These liners carried the wealthy in luxurious settings, but it was the steerage passengers – cramped in small staterooms below deck – who made it viable to build such large ships. It was, in a sense, all about carrying as many people as possible across ‘the pond’.

One of the companies embroiled in this fierce competition was the Holland-America Line, or HAL, which had started its business back in 1872 with their first steamer – Rotterdam. The company’s official name was Nederlandsch Amerikaanische Stoomboot Maatschappij, and the abbreviation of this – NASM – was suitably emblazoned on the line’s green and white houseflag.

During the closing years of the 19th century, Holland-America Line was enjoying prosperous times, and it was decided to expand the fleet with three new sister ships, the largest yet for the company. The contract for the first ship was granted to the German shipbuilding yards of Blohm & Voss in Hamburg, while the following two sisters would be built in the Irish yards of Harland & Wolff, Belfast. It was also the Belfast builders who designed the new trio, so even though she was built in Germany, the first ship was of Irish design just like her younger sisters would be after her.

Laid down as yard number 139 at Blohm & Voss, work proceeded on the new ship until, on December 15th 1899, the day of launch finally arrived. The new ship – the first of her class – was christened Potsdam, and was then sent down the ways into her proper element. However, there was still work to be done. Now she was to be fitted out with her engines, and craftsmen of different types were to transform her innards into comfortable passenger areas. Just short of five months later, the new ship was delivered to HAL on May 5th 1900 after satisfactory sea trials. She was now ready to start her career as a Holland-America liner.

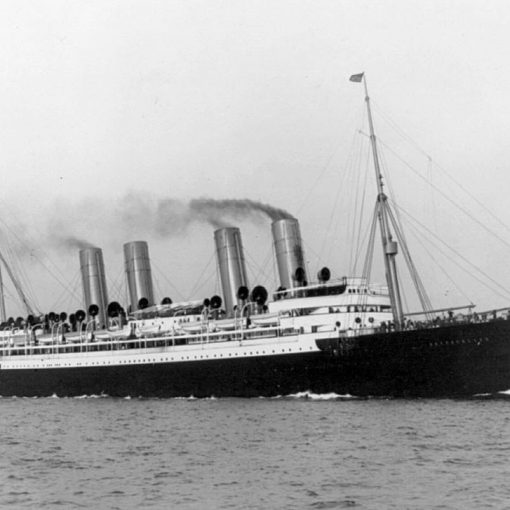

Just twelve days after her delivery, the Potsdam set out from the port of Rotterdam on her maiden voyage on May 17th, bound for New York. At over 12,000 gross tons she was the largest HAL liner yet, and she sported the classic steamship look with two masts and a single funnel painted in the colours of Holland-America Line – yellow, green and white. She measured 571 feet from her straight stem to the tip of the counter stern, and she was indeed the latest masterpiece of the Dutch merchant marine. But although fitted with luxurious First Class areas and comfortable Second Class staterooms, there could be no misunderstandings about her primary role as an emigrant ship when looking at her carrying capacity; 282 people in First Class, 210 in Second and as many as 1,800 people in Steerage.

Potsdam went through her first summer of service on the North Atlantic, but she quickly proved to be slowish and it was not long before she was known as a ‘poor steamer’. The cause of this soon turned out to be insufficient flue draught, and the company decided that something had to be done to remedy this unfortunate flaw. So, during her first winter overhaul from 1900-1901, the Potsdam’s funnel was heightened by a full 23 feet, or nearly seven metres, to improve the draught. When she emerged from the refit, her funnel was an easily identifiable feature that soon earned the ship a suitable nickname – ‘Funneldam’. Nevertheless, the cure had been successful, and Potsdam’s speed had been noticeably improved. The original flaw left one scar though, as the ship never had any reserves of speed.

Returning to service, Potsdam settled into her service on the North Atlantic. In the following years she was joined by her two sisters; Rijndam in October 1901 and Noordam in May the year after. As ships of the same basic design, they were in most aspects very similar to the Potsdam, but their Harland & Wolff-built machinery proved better than the German-built one of their older sister. Thus, Potsdam became the only one of the class to sport the extremely tall funnel, although the funnels on the two sisters were slightly taller than in the original design.

So, known by many as ‘Funneldam’, Potsdam continued her service with the Holland-America Line. The shipping industry continued to prosper, but in 1912 an event took place that shocked the world. White Star Line’s brand new Titanic– the largest and most luxurious liner in the world at the time – collided with an iceberg on her maiden voyage and sank with a loss of more than 1,500 souls. At this point, the steamship design had come to such a stage that such an accident had been unthinkable. But the fact that Titanic indeed had foundered, and perhaps most importantly that she had not carried enough lifeboats to accommodate all her passengers, made all shipowners rethink their safety procedures. HAL was no exception. The Potsdam was given two extra pairs of lifeboats, fitted aft on a deckhouse.

And at this time, a menacing dark cloud was looming on the horizon. As the political situation in Europe grew more and more tense, the danger of a great conflict became a very real fact. And so, in the summer of 1914, the shots in Sarajevo triggered what was to become World War I.

As a nation, the Netherlands kept a neutral position, but submarine warfare in the Atlantic endangered the line’s vessels. To protect them as much as it was possible, the Holland-America ships were painted with neutrality markings – the ship’s name and home port in large letters – on their sides. But the war resulted in a serious decline in passenger numbers, and the Potsdam was subsequently laid up at Rotterdam for sale.

But, as it were, there was another company that had a great interest in the laid-up Potsdam. In Sweden, the Broström Group was realising the dream of a Swedish transatlantic shipping line. Originally the plan had been to build two 18,000-ton ships to start operations, but it was soon realised that this idea had to be revised. So instead, the newly-formed Swedish American Line (SAL) purchased the Potsdam in September of 1915, and renamed her Stockholm.

The Swedish American Line was in many ways a result of the great emigration. The idea was to provide a route from Sweden to America without any unnecessary detours, as well as giving the emigrants a chance to sail on a Swedish ship with a Swedish crew. With the Stockholm, the new service could soon begin. But first, the ship had to be brought up to contemporary Swedish standards, mainly in the Third Class areas.

When finished, the Stockholm was ready to inaugurate SAL’s sailings. But before she set out on her second maiden voyage, a gala dinner was held on board to celebrate the birth of the new company. This attracted a great deal of attention in the press, and had Sweden’s Prime Minister Hjalmar Hammarskjöld as guest of honour. Then, finally, on December 11th 1915, Stockholm sailed out from Göteborg bound for New York. It was a joyous occasion, but there were a few reminders about the fact that war was raging in Europe. For one thing, the ship was painted with neutrality markings. And during the crossing, she had to call at Kirkwall to undergo an inspection for contraband.

Thanks to Sweden’s neutrality, the new company soon prospered despite the fact that they had only one ship in their fleet. But the service had to be postponed after two years, when unrestricted submarine warfare was introduced on the North Atlantic. Neutrality markings were no longer protection from lurking U-boats, and so the Stockholm was laid up at Göteborg in May 1917.

But when the bloody conflict finally came to an end in 1918, SAL could recommence their sailings. After a little more than a year in lay-up, Stockholm resumed her service in June. But despite that the war was over, there was much work to be done before everything would be back to normal. Soldiers from many nations had been brought in to fight the war in Europe, and now those who had survived were to be shipped home again. So, in 1919 the Stockholm was chartered to the United States for troop repatriation.

Shortly afterwards, the Stockholm was returned to the Swedish American Line, still as their only vessel. But this came to an end in February of 1920, when the Virginian was bought from the Canadian Pacific Railway Company and renamed Drottningholm. At last, the Stockholm had a fleet mate. SAL’s intention to improve their fleet was also reflected when in 1922 the Stockholm was sent to the yards of Götaverken in Göteborg for conversion into oil-firing. This refit greatly enhanced the performance of her engines, and therefore the funnel was reduced in length by some seven feet, or two metres.

At this time, after only two years of service, the Drottningholm was also in need of a refit. Through her career, her machinery had not been working quite satisfactory, and SAL had now decided to do something about it. However, the absence of Drottningholm resulted in a gap that had to be filled somehow. As fate would have it, this gave the Stockholm a chance to get reacquainted with her Holland-America Line ancestry, when her sister Noordam was chartered to SAL in 1923 and temporarily renamed Kungsholm.

But this was merely a short reunion. After only a year in Swedish America service, Noordam was returned to the Holland-America Line, and the Drottningholm could resume her duties with the company. Together with Stockholm, the two ships provided a link between Sweden and USA. However, the great emigration wave for which the line had been created was now wearing off. In fact, at the time of the company’s birth back in 1915, the emigration had already started to decline. 1923, however, became known as the year of ‘the last wave’ of emigrants. After that, it was all over. SAL had been too late to earn a big share of the business, and now they had to rethink their strategy.

The company would no longer function as a route to a new life for emigrants, but as a link between the former emigrants and their former homeland. And by this time, the cruising industry was beginning to take shape, and SAL wanted ships to earn their share. In 1925, the brand new Gripsholm was delivered, and she was followed three years later by the second Kungsholm.

By now, the old Stockholm was considered surplus of the SAL fleet, and on September 29th 1928 she set out on her final voyage for the Swedish American Line. The following November, she was sold to the Norwegian whaling company Atlas. Under their ownership, the ship was sent to Götaverken for conversion into a whale factory ship. For this less glamorous purpose, she was renamed Solglimt, and she entered service in her new role on September 12th 1929.

Solglimt remained in service as a whaling ship for another decade, although she was sold to the company A/S Thor Dahl in 1930. When World War II erupted in 1939, she continued her operations. But as a Norwegian ship, her career would soon take another turn.

Germany invaded Norway in the spring of 1940. A few months later, while in the Antarctic, the Solglimt was captured by the German auxiliary cruiser Pinguin (formerly the liner Kandelfels) on January 14th 1941. As a prize, the ship was taken to Bordeaux with a cargo of whale oil and taken over by the Erste Deutsche Walfangesellschaft (First German Whaling Company). Renamed Sonderburg, she was now put under the German flag and used as a supply ship in various French ports.

In 1942, the Sonderburg was anchored in Cherbourg when the port was under several air raids. The ship subsequently sank in the harbour due to the damage she sustained. She was salvaged at a later date, but there were not enough resources to repair her damages. Two years later, on June 15th 1944, she was scuttled by the Germans and sunk as a block ship when Cherbourg was evacuated.

The wreck remained in the port of Cherbourg until peace was achieved in Europe. In August of 1946, the French partly demolished the ship with explosives in order to clear the port. The final remains of the former Potsdam were raised in January the following year, towed to Great Britain and scrapped there. Thus ended a long and eventful career in maritime history.

Specifications

- 571 feet (174.5 m) long

- 62.2 feet (19 m) wide

- 12,606 gross tons

- Triple-expansion steam engines turning two propellers

- 15 knot service speed

- Passenger capacity of 2,292 people