1936 – Present Day

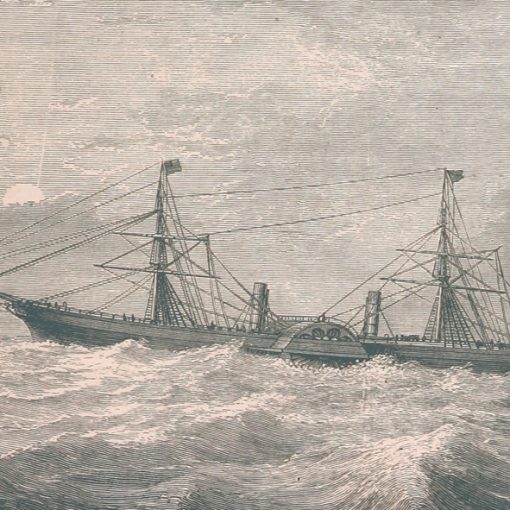

The British shipping industry had always been part of the absolute top in the world. Ever since the dawn of modern time had the British merchant ships – and the warships – been a pattern for the rest of the world to follow. With the revolutionary 19,000-tonner Great Eastern, the British engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel had set the pattern for the future ocean liner in 1860. Not only in size, but also in speed was the British an ever-returning factor on the Atlantic. The White Star Line’s Teutonic and Majestic held the famous Blue Riband in the early 1890s and the Cunard Line’s Campania and Lucania took over the prize until 1897. At that time the Germans snatched the Blue Riband and kept it until the arrival of the Lusitania and Mauretania in 1907. But those German liners were not close to the Great Eastern’s size, and not until the Lusitania did the two factors – speed and size – come together in one ship. Thereafter did that combination never exist, at least not for the coming thirty years.

The post-World War I period had been a time when the British operated old ships from the early 1910s. These ships were either British-built ships like the Olympic and Mauretania, or vessels seized by the British government from the defeated Germans – vessels such as Berengaria (ex-Imperator), Majestic (ex-Bismarck) and Homeric (ex-Columbus). These were all distinguished ships but as the 1920s came to an end, it was evident that the prime ships of the British merchant fleet were getting old. The prime ships in the world were now owned by the distinguished French Line (Compagnie Général Transatlantique – C.G.T.) or the respected Norddeutscher Lloyd. The fabled luxury-liner Île de France had entered the waves in 1927, and immediately become one of the most popular passenger vessels on the North Atlantic. She had replaced the celebrated Paris who had glamorously served the French Line since 1921. The two German greyhounds Bremen and Europa came in 1929 and 1930, and with their arrival the grand old Mauretania finally lost the Blue Riband. Both the Cunard Line and the White Star Line realised that something had to be done in order to save Britain’s lost pride.

The first of the British companies to act was the White Star Line. With new enthusiastic leaders, the company ordered a vessel measuring 1,010 feet – the longest decided upon to date. The ship’s name would be Oceanic. At the same time across the English Channel the French Line gave their order to build a ship bigger still at almost 1,030 feet. The Cunard Line also wanted a part in the race and started planning a project consisting of building a 1,020-footer to rival White Star and C.G.T. All of the three ships would have a service speed of around 30 knots.

As time would prove, this was a bad time for the construction of new ‘superliners’. The White Star Line had already severe financial troubles, due to some bad investments, when they ordered the Oceanic in 1928. Vessel after vessel in the former so magnificent White Star fleet went to the scrapyards without planned replacements. The building of the Oceanic made things even worse for the company. In 1929 came the Great Crash on Wall Street. This affected the entire world, including the already staggering White Star Line. On July 29, 1929, they had to cancel the construction of the Oceanic. Almost the entire keel of the ship had been laid, and the steel was recycled into a smaller but otherwise similar vessel – the third Britannic.

The French Line managed to keep up the work on their vessel because they were granted a massive loan from the French Government. This loan was given with the term that the Government would be given control of the French Line. Back in Britain, the Cunard Line thought themselves fortunate to not have started the building of their vessel when the Great Crash came. They figured that if they could complete the ship before the world’s economy recovered, they might end up with a very cheap bill for the ship. The work on the unnamed ‘Hull 534’ began in December 1930 on the John Brown Shipyard, but as times grew harder and harder, Cunard could no longer afford to continue construction on the vessel. In December 1931 the work was put on hold, but not cancelled. A skeleton crew was maintained to keep the empty hull in adequate condition, should construction ever restart.

The British watched with enviousness as the French Line’s brand new Normandie slipped into the Loire River at St. Nazaïre on October 29, 1932. It seemed that the ultra-modern Normandie would be the only of the projected three 1,000-footers to be realised. In Britain, the giant ‘Hull 534’ sat rusting in its gantry. The Cunard Line had simply not enough money to make any progress. Desperate, and in nationalistic words, the shipping company turned to the British Government for a loan that would help them complete the corroding Normandie-rival. The Government had aided the Cunard Line before, when producing Lusitania and Mauretania.

To continue the work that had stopped four years earlier was not an easy task. The entire hull was covered with tons of rust, and the gantry and other construction equipment had to be completely overhauled. The restoration back to the conditions of 1930 took several months, but since the workers knew that this would put Britain back in the race, they proceeded with pride and efficiency. Five months after the work had been restarted, ‘Hull 534’ was ready for her launch.

But as Cunard would carry out a launch, they needed a name for the ship. After many suggestions the name Victoria had been decided upon. The name referred to the successful British queen of the 19th century, and this needed a royal request – a required formality. Sir Percy Bates and Sir Ashley Sparks, two men of the Cunard management, were selected to inform King George V of the decision. Sir Ashley put it this way: ‘Your Majesty, we are pleased to inform you that Cunard wishes your approval to name our newest and greatest liner after England’s greatest queen’. The king misunderstood the request – deliberately or not – and replied: ‘My wife will be delighted’. Cunard could do nothing; you do not correct the king in such a delicate matter. The present queen was named Mary, so the new name for the vessel was destined to be Queen Mary.

This anecdote has been widely contested ever since Frank Braynard published it 1947 in his first book ‘Lives of the Liners’. However he was finally proven right in 1988 when he attended the same dinner party as Eleanor Sparkes, daughter of Sir Ashley Sparkes. She opened the conversation with her table neighbour Braynard by telling her ‘favourite ship story’. She told the exact same anecdote that Braynard had published in his book. Ever since have the story been more respected.

The 26th day of September was a rainy day. Nevertheless had loads of enthusiastic British nationalists, ship-buffs and of course the thousands of workers and designers that had worked on the Queen Mary gathered around the titan bow. The gathering was crowned by the royal family standing on a special designed platform with a glass-screen to prevent the royalties from getting soaked. The queen dropped a bottle of Australian wine against the bow, and thereby the ship started its motion towards the River Clyde. The Queen Mary was a very long ship; the longest constructed in Britain. The river had had to be further dragged to receive the 1,018-feet hull. But in spite of this, the stern grounded on the opposite end of the river because of the unaccounted speed the ship had reached on its way down the slipway. But there were no damages and the fitting out could commence.

During the fitting out, the design of the ship became more and more apparent to the world. Supposed to be a rival to the French Normandie, the Queen Mary could not compete in modernity and sleekness. She represented the British conservatism, and one could say that she was a larger replica of the 1914-built Aquitania. But in size the Queen Mary seemed to overshadow the Normandie. At 81,000 tons, the Queen exceeded the 79,280 French gross tons. But just as the British would claim to have the largest ship in the world, the French Line announced that the Normandie would be enlarged to over 83,000 tons before the Queen Mary’s maiden voyage. The French seemed to have every advantage.

When the Queen Mary was finished fitting out and left the River Clyde on March 24, 1936, the Normandie had already sailed on the transatlantic route for almost a year. After a not too dangerous run-aground in the narrow river, the Queen headed for Southampton. Once there, the royal family would once again visit the ship. The queen toured the Queen Mary with interest, and in spite of her all-through conservative mind, she seemed to have enjoyed the tour. That evening she wrote in her diary: ‘Toured the new Queen Mary today. Not as bad as I expected’.

The Queen Mary was a modern ship, but not ultra-modern as the Normandie. If the Normandie had entered service after the Queen Mary, the Queen would possibly have been talked about as the most beautiful liner ever built – inside and out. But now it was the contrary. Every critic compared the ship with the Normandie. The British combination of traditionalism and modernity was considered too sterile by the some critics of the 1930s. But whatever said, the Queen Mary was a beautiful ship – inside and out. Her interiors had over fifty different woods, collected from all over the British Empire. Inside the Queen Mary’s staterooms, you could easily make out that you were on a ship. Previous liners had disguised their interiors to palaces and manor houses, but the Queen was not afraid of looking like a ship. Around the vessel nautical touches were displayed and the round portholes were proudly exposed. The first class lounge was a two deck high creation with little groups of tables and chairs cosily put together around fireplaces and in the room’s corners. But perhaps the highlight of the ship was her first class dining saloon. The long tables of the old ocean liners had been long gone, and just as in the lounge the tables were grouped with two to four chairs a each. For larger companies bigger tables were naturally available. On the short-side wall a giant map of the Atlantic was mounted. It showed the exact position of the Queen Mary during a transatlantic voyage. When Queen Elizabeth entered service after the war, you could see the position of the sister-vessel as well, and thereby knowing when they would meet on the Atlantic. The first class accommodations were vast with plenty of elbow room, all with a light touch of Art Deco, the new type of art introduced by the Île de France in 1927. One beloved feature was the small and exclusive Verandah Grill, just below the main mast.

The Queen Mary had been intended to have three classes: First, Second and Third. But the Americans had introduced two vessels during the Depression that featured three different classes: Cabin (First), Tourist (Second) and Third (Third). At considerable lower fares than the traditional three-class system, the American ships attracted the most passengers. The other shipping lines in the world had to follow. So, when the Queen Mary entered service, she did so with the new class system.

In May 1936, it was announced that the Queen Mary’s maiden voyage would take place in the beginning of July. It was no secret that the Queen aimed to snatch the Blue Riband out of Normandie’s hands. The Normandie had been very secretive about the will to take the Blue Riband in possession from the Italia Line’s Rex, but when she arrived in New York after her triumphant maiden record-voyage in 1935, the crew members received a medallion on which is was printed: ‘Normandie – The Blue Riband’. All along, the French had aimed at the Blue Riband – the fight for the prize had become a fight between two rivalling leviathans.

On July 1, 1936, the Queen Mary set out on her maiden voyage. As the voyage came to its end, the passengers realised that the Blue Riband was in the ship’s reach. But as a touch of fate, the Queen Mary was surrounded by fog after two thirds of the voyage. The ship slowed down to a crawl and the Blue Riband immediately went out of sight. As soon as the fog had lifted, the Queen Mary pushed her engines to the fullest, averaging 32 knots for the rest of the voyage. When she arrived in New York she had completed the voyage in four days, twelve hours and twenty minutes. The Normandie had been 38 minutes faster. But considering that the Queen Mary had carried through a distance of her voyage at a very slow speed, the British knew that the Blue Riband soon would be theirs.

And right they would be. But before any new record-voyage could take place, the teething problems of the Queen Mary had to be remedied. At a thirty knot speed, she vibrated violently at the stern, and in bad weather she developed a nasty corkscrew motion. A third problem was that the funnels allowed smoke to cover some of the after promenade decks. The lower interiors of the ship were stiffened and the propellers redesigned. This reduced the vibration considerably, but the corkscrew motion could not be bettered – not yet at least. Smoke-washing devices were installed in the funnels, which erased the problem of soot in the passengers’ throats.

With the teething problems remedied, the Queen Mary made another run for the Blue Riband on August 31. When she reached New York harbour at the end of the voyage, she had managed the distance in three days, 23 hours and 57 minutes – the first time the crossing over the Atlantic had been made in fewer than four days. The next year on March 19, the Normandie regained the title of being the fastest ship with an average crossing speed of 31.65 knots. But the Queen Mary was still able to further push her engines, and in August 1938, the Queen Mary retook the Blue Riband with a crossing time of three days, twenty hours and forty minutes. The distinguished honour would remain in British hands for nearly fifteen years. The Queen Mary had proved to be the faster ship. Even though the Normandie’s hull was far more streamlined, the Queen had much more powerful and efficient engines.

It was not only in speed that the Queen Mary outmatched the French ship. For some reason the passengers favoured the British ship. The Normandie seldom travelled at full capacity, whilst the passengers flocked the Queen Mary – the rich and the poor. The conservative British aristocracy chose her before the French liner – unsurprisingly, but also businessmen and ordinary tourists. There was something attracting in her homey, unpretentious interior. The Normandie’s movie-star glitter made people feel as they were ‘living in a cathedral’. Through the 1930s, the Queen Mary carried the largest loads of passengers. But as the century was about to end, the almost forgotten German eagle had once again awoke, and required revenge for the lost World War I. Another large-scale conflict was about to strike the world.

The Austrian Adolf Hitler had reached the very top seat of power in Berlin when he was declared Reichskansler in 1933. He forbade labour unions and other political parties. The Jews were to be exterminated in the concentration camps. Another goal Hitler had was to expand Germany’s borders. At first he only claimed the surrounding German-speaking parts of Europe. But when he continued with Czechoslovakia and Poland, the rest of the world could not sit idle any longer. The British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain declared to Hitler that if his troops had not left Polish lands by September 3, 1939, his country with its allies would declare war on Germany. Hitler refused and the Second World War was a fact.

Just as in World War I, the British, as well as the other participating countries, would need troop-ships. The Queen Mary and her still-building sister Queen Elizabeth would be perfect transports. But the two Queens were not to be used in the absolute beginning of the war. The Queen Mary lay berthed at Pier 90 in New York harbour together with the Normandie until 1940. That year, the Queen Elizabeth made her secret maiden voyage across the Atlantic, and joined the other two leviathans. For two weeks, the world’s three largest liners were berthed side by side. The Normandie remained in her peacetime colours, but the Queen Mary was repainted grey at her pier. When the two weeks had passed on March 21, the Queen Mary sailed for Sydney, Australia where her interiors were refitted in order to accommodate 5,000 soldiers. Shortly afterwards the Queen Elizabeth too left with the same destination. The Normandie was left alone in New York harbour.

The former rival of the Queen Mary remained in New York, with a French skeleton crew attending her. However, after some time the Americans seized the vessel. At first they wanted to convert her into an aircraft carrier, but that project was abandoned. With the Americans in charge the Normandie was more and more neglected, and finally a worker on board the ship managed to set the ship on fire in 1942. When trying to kill the blaze, the New York Fire Department pumped too much water in the ship’s upper structure. By the next day the Normandie wallowed over onto her port side, almost totally burnt out. She was later righted and towed away, but it was too late. The only worthy rival to the British was forever gone.

After having been completed as a trooper in Sydney, the Queen Mary started to sail between Sydney and Suez together with the Queen Elizabeth. The two ships had been designed for the cold North Atlantic and as they now crossed the equator frequently, the soldiers used to pack the upper decks. The venerable old Aquitania also served in the war, and since she was built long before the invention of air-condition, she was the most unfavoured ship because she was so hot. But as the grand old dame she was, she performed brilliantly throughout the conflict.

The Japanese attack of Pearl Harbor in December 1941, meant changes for the Queen Mary. She returned to her North Atlantic run, after having shipped 20,000 American soldiers to Australia in order to strengthen the weak defence there. In Americans hands, the Queens expanded their trooping-capacity. Now they should be able to carry 15,000 men – nearly eight times more people than in peacetime service. Every possible space was remade in order to give the soldiers somewhere to sleep. To accommodate even more, the soldiers slept in shifts. On one crossing in 1943 the Queen Mary set the present record of people on board a ship – 16,683 souls. That crossing she averaged nearly 29 knots, but had lifeboat accommodation for merely 8,000 people. The Queen Mary continued on the North Atlantic run for the rest of the war, carrying more troops than she would ever carry peacetime passengers. Winston Churchill sailed on the Mary several times to negotiations with his American ally. In his memoirs he wrote: ‘Built for the arts of peace and to link the Old World with the New, the Queens challenged the fury of Hitlerism in the Battle of the Atlantic. Without their aid the day of final victory must unquestionably have been postponed’.

During one crossing towards Europe in late September 1942, the Queen Mary was zigzagging north west of Ireland in a convoy of ships. Suddenly the British light cruiser Curaçoa went across her bow and the 81,000-ton Queen sliced the vessel in half. The Curaçoa sank immediately with the loss of 338 men. Being in delicate waters the Queen Mary continued her voyage, seemingly undamaged. When she was overhauled a hole ‘as big as a house’ was revealed in the ship’s bow. During later years the Queen Mary have been accused of not zigzagging at the moment, and therefore confusing the Curaçoa.

On May 7, 1945 peace had finally come to Europe as the German forces capitulated. Total peace was achieved on September 2, when the Japanese signed their unconditional surrender. By October, the British Government allowed Cunard to paint the Queen Elizabeth’s funnels in Cunard livery for the first time. By 1946, she could go through her ‘maiden voyage’, even though she had sailed for the past six years. The Queen Mary was also returned to Cunard shortly after the war and put back in transatlantic service.

The 1950s proved to be a prosperous period for the two Queens. They sailed with plenty of passengers between Southampton and New York. It was not uncommon with as many as four comings and arrivals a week. The Cunarders gained immense popularity on the North Atlantic passenger trade route. Their size made people choose them because of the safety and the famous reliability. Together with the Normandie, the Queen Mary and the Queen Elizabeth were the largest vessels ever to use the port of New York. Since they both had the extraordinary deep draught of 39 feet the harbour constantly had to be dragged. Sometimes the Queens had to move with the ever-changing tide. At some occasions when one of the Queens arrived in New York they found that the docking personnel was on strike, and the giant ships had to dock for themselves, relying on their own manoeuvrability. The process to dock with the tug-boats took about half an hour, but without their aid it could take two hours.

During the post-war years, the Queen not only enjoyed popularity among the average passenger, lots of celebrities chose to take the Queen Mary for the voyage to America or Europe. Some of the most noted names are Charles Boyer, Spencer Tracy, Madeleine Carroll, Sir Winston and Lady Churchill and of course the beautiful Greta Garbo.

One event, however, in the fifties was not pleasant for the Queen Mary. In 1952 she lost the Blue Riband to the brand new American ship United States. With engines designed for aircraft carriers she developed 240,000 horsepower. With that power she cruised across the Atlantic with an average speed of over 35 knots. There was no way the Queen Mary could re-capture the lost honour. But, as mentioned, the Queen Mary enjoyed such popularity that losing the Blue Riband did not affect the number of passengers sailing on her. But soon another threat appeared.

In 1961, the first aerial connection between Europe and America opened. This meant that a passenger could choose to travel across the Atlantic at 30 or 35 knots on board the Queens or the United States, or make the voyage at 500 knots in an aeroplane. More and more of the liner’s passengers now instead went across the Atlantic inside a small air-borne machine, than on a comfortable ship.

Many of Cunard’s vessels now started to concentrate on cruising for tourists on voyages without destination. The second Mauretania’s planned ‘sister’ Caronia of 1949 went into service as a genuine cruise ship. Even the two Queens made some cruises to Nassau and the Canary Islands in the early sixties.

But cruising could not keep the declining Queens running. In 1967 it was announced that both the Queen Mary and the Queen Elizabeth would be withdrawn from service. The future plans for the two vessels were many. Some investors thought of turning the Queen Mary into a giant immigrant ship between Britain and Australia, others wanted to make her into a giant floating high school at the Brooklyn waterfront. But the highest bid was made by Japanese scrap merchants – $3,250,000.

The Queen Elizabeth was sold to a Hong Kong business tycoon and was to become the floating university Seawise University. Sadly, she suffered from the same tragic end as the Normandie when she, almost completed, caught fire and was capsized by water-pumping firemen. She remained on the spot and was scrapped in 1973.

The Queen Mary was the only one left. Would she too disappear from the face of earth? Fortunately, as a touch of fate, the Californian city of Long Beach made a higher offer than the Japanese scrappers; they were willing to give as much as $3,450,000. The Queen Mary was saved! She was chartered by a New York travel agency for the voyage to California. On this last sentimental voyage she carried cruise passengers from Southampton around South America to Los Angeles. After forty days at sea she reached her destination on December 9, 1967. Once in Long Beach the Queen Mary was relieved of her propellers and underwent a $72,000,000-refit (!) into the ‘Hotel Queen Mary’ emerging in May 1971. She has remained there ever since.

Through the years, the Queen Mary has been the natural place to go when making movies about ships. In the early 1970s the film ‘The Poseidon Adventure’ about the ageing vessel Poseidon hit the screens. The plot was about an old distinguished liner that capsized on her final cruise before retirement. And in 1979, the Queen Mary played the role of the Titanic and could be seen in the movie ‘S.O.S. Titanic’. The 1997 James Cameron film ‘Titanic’ made the interest in the liner grow even bigger. She lies secure in Long Beach, her position as a static vessel presenting its own set of challenges. In the summer of 2017, an extensive survey found that the hull and other parts of the ship’s structure were corroding, endangering the Queen. It was estimated that repairs would cost $300 million, to which the city of Long Beach contributed $23 million in order to cover the most vital work needed. With the ship having passed into her eighties by now, there is still much work that needs to be done to keep her structurally sound. Fortunately, there are many forces in both her adopted country as well as her native Scotland at work to keep the Queen Mary alive and well.

Specifications

- 1,018 feet (310.9 m) long

- 118 feet (36 m) wide

- 81,235 gross tons

- Steam turbines powering four four-bladed propellers

- 29 knot service speed

- Passenger capacity of 2,139 people