1905 – 1955

Also known as Drottningholm, Brasil, and Homeland

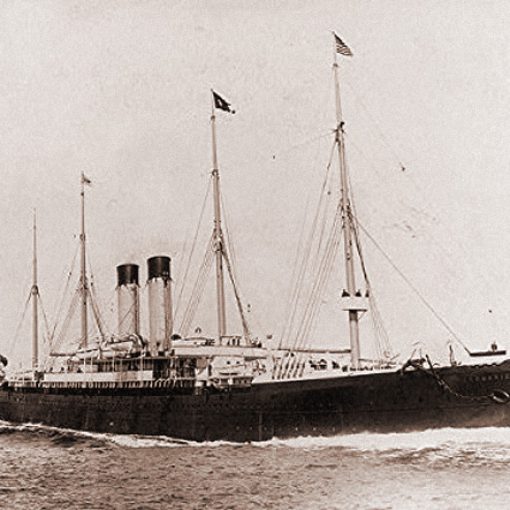

In the first years of the 20th century, the Glasgow-based firm of Allan Line decided to commission two new ships for the company. Naturally not known to them at the time, one of these vessels would live to sail on the high seas for nearly half a century, with several different companies and bearing a variety of names and liveries.

The two sisters were originally ordered from the Belfast yards of Workman, Clark & Co., and the first of the two sisters was launched and christened Victorian on August 25th, 1904. If all had proceeded as planned, the second vessel would have been launched at the same yards shortly afterwards. However, due to shortage of time and labour, the order for the second ship was instead given to Alex Stephen & Sons, Glasgow. On December 22nd 1904, the new ship entered the water for the first time. She was given the name Virginian.

The most noteworthy feature of the new pair of ships was found in their engine rooms. The Victorian and Virginian were the first liners on the North Atlantic powered by steam turbines, and the first to be fitted with triple screws. Irish scientist Charles Parsons had come up with the idea of a turbine-driven ship in the mid-1890s, and his triumph came in 1897, at Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee Grand Naval Review. Parsons had built a boat of his own – the Turbinia – and fitted it with his turbine engine. The Turbinia’s speed and agility was effectively demonstrated during the Naval Review, and the passenger shipping companies took interest in the new type of engine. The new Allan liners were the first to be fitted with such engines, and Cunard’s Carmania followed later the same year. Her success would ultimately lead to the turbine powered ocean greyhounds Lusitania and Mauretania.

On April 6th 1905, the Virginian set out on her maiden voyage from Liverpool to St. John, New Brunswick. After this crossing she was transferred to the Montreal run, for which she was intended. But at this early part of her career, the Virginian suffered from problems caused by her revolutionary power plant. Since no one had any experience in building turbine driven passenger ships, there had been some miscalculation during construction. The efficient speed of the turbines was too fast for the relatively small propellers and the ship’s hull design. Not only did this cause vibrations, but also cavitation. Simply put, one can compare this to the skidding of a car on a slippery surface; the propellers had a bad ‘grip’ in the water. Naturally, this led to unnecessarily high fuel consumption. It was also soon discovered that the new ship had a tendency to roll violently in heavy seas, a problem that would haunt her for the remainder of her career.

But in spite of these problems, the Virginian’s engines gave her enough speed to set new records on the Canadian run when on June 16th 1905, she covered the distance between Cape Race and Moville in four days and four hours. But as with any liner, the Virginian also had her taste of poor fortune. In September 1905, the smoke from a forest fire caused bad visibility, and the ship went aground on Cape St. Charles, St. Lawrence. Luckily, she was freed and came off safely.

Following this early incident, the Virginian lived through some more or less uneventful years, serving the Allan Line on the Montreal route quite satisfactory. But in 1912, on the night between April 14th and 15th, she played a small role in the most known maritime disaster of all times. The new White Star liner Titanic, claimed to be unsinkable, struck an iceberg off Newfoundland and started going down by the head. The Virginian was one of the ships who picked up her distress calls, and she immediately set course for the stricken Titanic. However, the Virginian was quite far away and it would take her some time before reaching the scene of the disaster. And so, when the Cunarder Carpathia signalled that she was only 58 miles from the Titanic, the Virginian resumed her previous course and continued her passage.

Two years later, in 1914, another great maritime disaster played a great role in the life of the Virginian. In the cold and misty waters of the St. Lawrence River, the Canadian Pacific liner Empress of Ireland was hit by the Norwegian collier Storstad and sank in just 14 minutes, taking with her 1,024 souls into their death. An enormous tragedy indeed, and Canadian Pacific quickly needed another ship to fill the gap of the lost Empress of Ireland. For this purpose, the Virginian was chartered by Canadian Pacific to serve on their Liverpool-Montreal run. The Virginian sailed a few voyages in this service, but was soon interrupted by the outbreak of World War I.

In August of 1914, the Virginian was taken over by the British government for use as a troop transport. She served as such for a few months, and was then taken in for conversion into an armed merchant cruiser. When converted, she was assigned to the 10th Cruiser Squadron along with her sister, the Victorian.

In 1917, in the midst of burning war, Canadian Pacific Railroad Co. acquired the Allan Line and all of its holdings. The Virginian and her sister were transferred to CPR, but remained in government service. This service continued through the conflict, and the Virginian seemed to live through it unscathed. Yet in the dying days of the Great War, she was torpedoed and started to go down. In order to save his command, the Virginian’s captain managed to beach the ship on the coast of Ireland. The damage to the ship was quite severe, and she was brought to the Princess Dock in Glasgow for reparation work.

In 1918, when the war finally came to an end, the Virginian was still laid up. She was sent back to her builders for refurbishing in December that year, but was soon declared surplus. Canadian Pacific had received former German liners as compensation for wartime losses, and these ships were much more attractive for use in the rebuilding of their fleet. The Virginian was put up for sale, in wait of a possible buyer. The buyers soon emerged; they were the Swedish American Line. They had started their operations in 1915 with the former Holland-Amerika liner Potsdam, which had been renamed Stockholm. Now they were in search of a ship to serve as her consort, and they soon had their eyes set on the laid up Virginian. They purchase went through on February 14th 1920, and the Virginian was renamed Drottningholm.

As the Drottningholm, the ship was to serve the Swedish American Line, who mainly concentrated in earning their share on the emigration business. Upon delivery to SAL, the Drottningholm was taken to the yards of Götaverken in Göteborg, where she would go through a rather extensive refurbishing treatment. The most attention was given to the quarters in steerage, in which most emigrants would travel. The upper class accommodations already held quite high standards, but were nevertheless slightly refitted to meet the company’s requirements. In May of 1920, the Drottningholm set out on her premiere voyage from Göteborg to New York.

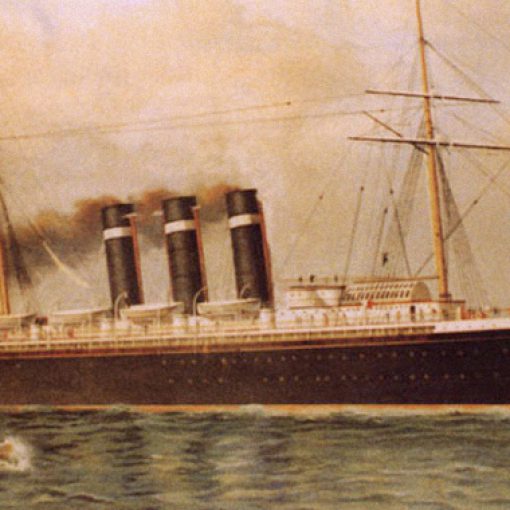

She proved a success. Her interior decorations were well received, and included public rooms that would soon become popular with the passengers. The promenade deck music saloon. With its high ceiling and cosy milieu, it soon became a natural gathering point on board the Drottningholm. Throughout the ship, one could sense the impression of space and comfort. But the company was not entirely satisfied with their new vessel. The problems caused by the turbines still remained, and in 1922 it was decided to try and remedy them. The Drottningholm was sent to Götaverken, where a new set of De Laval single reduction geared turbines was installed. The Swedish American Line was not opting for their ships to be fast, and the new engines were less powerful than the original ones. These more efficient turbines with their lower fuel consumption made the Drottningholm more economical to run. Her new service speed was set at 17 knots. The rolling of the ship could not be remedied as easily though, and this problem remained. Soon, the ship had been nicknamed “Rollingholm” or “Rollinghome” by frequent travellers.

In 1923, the Drottningholm returned to service. In addition to her new power plant, her bridge deck had been extended aft to the main mast. The Swedish American Line had been founded so that Swedish emigrants could travel directly from their old country to the New World on a ship with Swedish-speaking crewmen. But the company had really been too late to earn their share of the migration. Although the last wave of emigrants came in the 1920s, it was soon evident that the company would have to focus on another type of passengers. Following the First World War, the world had become a different place. National economics flourished, and ocean travel became more than just transportation from point A to point B.

So, instead of transporting Swedes to a new homeland, the Swedish American Line now started carrying one-time emigrants back to Sweden for short visits. In the opposite direction, they became a way for people in Sweden to visit relatives in America. And business was booming. The company was by now so successful that more ships were needed to meet the large number of bookings. A temporary solution was reached when in 1923 the company chartered the Stockholm’s sister Noordam from the Holland-Amerika Line. She served SAL for just about a year under the name Kungsholm. She was then returned to her owners, and SAL instead placed an order for their first newbuild – the Gripsholm. She was joined in 1928 by the Blohm & Voss-built Kungsholm. These two new ships stole the thunder from the old Stockholm and Drottningholm, which were cast out of the spotlights. Still, they remained reliable in their services.

The new Gripsholm and Kungsholm were repainted white after a few years in service, and this would soon become the traditional hallmark livery of the Swedish American Line. To bring her more into company familiarity, the Drottningholm was repainted white in 1937. Two years later, another global conflict erupted when Adolf Hitler marched into Poland on September 1st, 1939. Sweden was determined to stay neutral, and Swedish merchant ships were not to be used for military purposes. But the Drottningholm was nevertheless put to good wartime use along with her younger fleet mate, the Gripsholm. The two ships were used by the International Red Cross for the exchange of diplomatic personnel, civilians and wounded prisoners of war. The Drottningholm served from 1940 to 1946, making 30 passages and carrying some 25,000 people.

After the Armistice, Drottningholm was returned to SAL. However, they were now planning a replacement – the 12,000-ton Stockholm. When the new ship was delivered from Götaverken in 1948, the old Drottningholm was sold to the Home Lines, in which SAL had a share. With her new company, the Drottningholm was renamed Brasil. She made her first voyage, from Genoa to Rio de Janeiro, on July 27th 1948. Another former Scandinavian-familiar ship was used as her running mate, namely the Norwegian American Lines old Bergensfjord, which had been renamed Argentina.

The Brasil remained with the Home Lines and served them satisfactory. In 1951, she was brought to Italy where she was refitted and modernised. She emerged with a smaller gross tonnage and decreased passenger capacity. She was transferred to the Hamburg-Southampton-Halifax-New York service, and for this she was renamed Homeland. Although still formally owned by the Home Lines, the ship was managed by the Hamburg-Amerika Line.

The Homeland did not last long in this service, though. In 1952, she was instead put on a Genoa-Naples-Barcelona-New York route. The ownership was transferred to the Home Lines subsidiary Mediterranean Lines Inc. The old ship lasted for another three years. In 1955, she was evidently an old ship and she was then sent to the shipbreakers of Sidarma, located at Trieste. After nearly 50 years of service, the Homeland was the oldest ship in transatlantic service at the time of her withdrawal.

Specifications

- 538 feet (164.4 m) long

- 60 feet (18.3 m) wide

- 10,754 gross tons

- Steam turbines turning three propellers

- 18 knot service speed as originally built, reduced to 17 knots in 1922

- Passenger capacity of 1,712 people

One thought on “Virginian”

My grandfather came to America on the Virginian, landing at Montreal in 1910. I assume he traveled in steerage and I have wondered what that Atlantic crossing was like. I’m pretty sure he may have experienced the Infamous rolling.