1953 – 1956

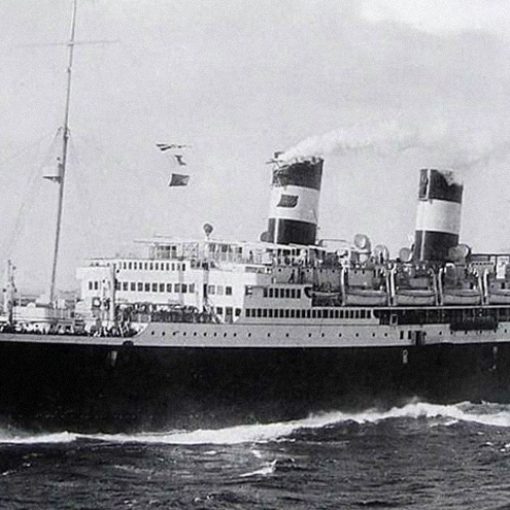

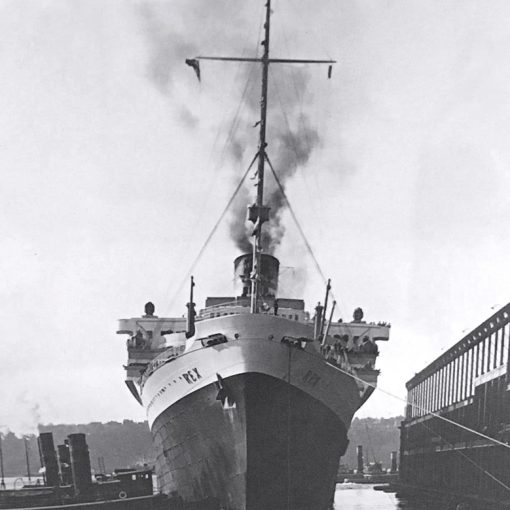

The Italians and their ships had not been the most wanted on the seas at any time before the 1930s. But in 1933 the Italian Line commissioned their new champion; the Rex. The Rex was something really special; it was the largest ship ever built in Italy, and it had the speed resources to take the Blue Riband from the German ship Bremen. This also happened, and the Rex possessed the prize until Normandie took it from her in 1935. The Rex was also an enormous ship; she was over 50,000 tons and 880 feet long. But the pride of the Italians did not last long. During World War 2, on September 8, 1944, the Rex was set on fire and sunk by Allied bombers near Trieste. The wreckage was gradually scrapped between 1947 and 1958.

After the hostilities, Italy had lost half their merchant fleet and was not able to show the world how good a seafaring-state they were. But in the beginning of the 1950s, it was decided that the Italian Line should build two new vessels to re-establish Italy’s pride. They were to be named Andrea Doria and Cristoforo Colombo. The size would not live up to the pre-war giants, and nor would the speed be in reach for the Blue Riband. But the ships should symbolise Italy’s new start after the lost war, and what was going to be the main thing about the sisters was their luxury, and prestige. But at almost 30,000 tons and 700 feet in length, it was not small ships that the Ansaldo Shipyard had to build.

On June 16, 1951 the Andrea Doria was launched. She was the first of her siblings and all the attention was thus focused on her. The huge mass of people that had gathered to witness the ship’s launch cheered and cheered and there seemed to be no termination of the happiness the Andrea Doria had given them. The ship did not only symbolise the new Italy; it also brought the Italian’s minds back to the leading position Italy had during the 16th century. The name ‘Andrea Doria’ itself was fetched from one of Genoa’s greatest sea heroes, and that certainly did not make the Italian’s minds any milder. Andrea Doria’s sister’s name’s origin is obvious.

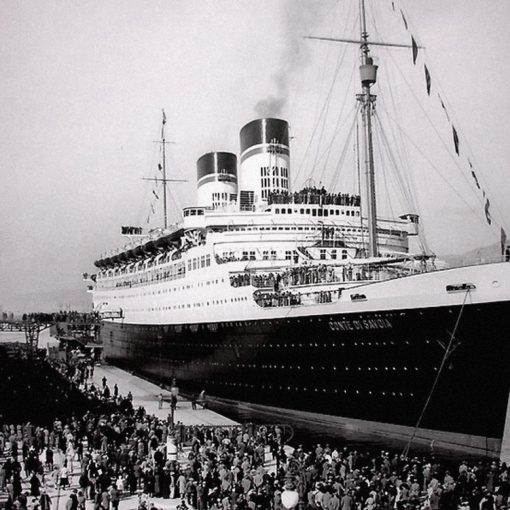

The Andrea Doria and her sister were ships not only admired for its beautiful interiors. Her external design was beautiful, and the proportions were almost perfectioned. A long black hull, on which a superstructure that grew towards the middle, housed one white funnel with a red top. Naturally, she followed her earlier sisters as the Rex and the Conte de Savoia, but as always it was the pioneering Normandie from 1935 that had set the pattern.

One other thing that the new ships were celebrated for was their safety. The Andrea Doria and her sister had hulls that were divided into eleven watertight compartments. Any two of these could be filled with water without endangering the ship’s safety. Another safety precaution was that her lifeboats (she had enough of them) could be lowered at a maximum list of twenty degrees. No one was ever afraid to board the new flagship of the Italian Line.

Even though the 1950s today seems as the decade of flight and retirement of the ocean liners, the beginning of the decade was in one way a golden age for North Atlantic ship companies. It was after the war, and everyone had to rebuild, and thereby show the rest of the world how able they were, and how little the war had affected them. For instance, in America the United States was launched, the everlasting holder of the Blue Riband, along with numerous other North American ships.

On January 14, 1953 Andrea Doria set out on her maiden voyage. After a brief stop at Cannes, she went through ‘the lock of the Mediterranean’ – Gibraltar – and then set off to New York. During this crossing it was noticed and confirmed that the ship had serious problems with her stability. Just as it had been predicted when a model was tested in water, the Andrea Doria gained too high a list when placed out of position by a large wave or any other significant nature force. When the new ship reached Nantucket outside North America’s coast she was struck by a wave so mighty that it gave the Andrea Doria a list of 28 degrees. The great list was partly explained by the fact that all her water supplies were emptied, as the custom is at the end of a crossing. But the fact that she had a problem with instability could never be escaped from entirely.

The captain that had commanded the Andrea Doria on her maiden voyage was Piero Calamai, a skilled captain that had the Italian Line’s full confidence. Even though he was a very good captain, he was not the sort of captain that sat and chatted with the passengers during the voyage. He used to retire to his cabin between his duties, and was almost portrayed as a shy person. But this shy man was very caring about his ship and wanted to have full control of everything that occurred on the ship he commanded. He was also a very conservative man, who put little trust in modern technique. He preferred to use his own eyes in front of radar machines and such. Ever since the maiden trip, Calamai had been the captain on Andrea Doria, his last voyage with the ship was decided to be a late July-crossing in 1956. Then he was supposed to be transferred to the Cristoforo Colombo.

This voyage started out as every other crossing and soon had Andrea Doria left the greater part of the Atlantic behind her. The ship’s staterooms and lounges were filled with people who enjoyed the comforts of an Atlantic crossing by ship. The vessel was almost filled to capacity, and this showed how popular and successful Italy’s new ship was.

At the same time, on July 25, 1956 the Swedish American Line’s Stockholm prepared for her departure from New York to Göteborg. She was scheduled to depart at 11.31 am, and was under the command of Captain Gunnar Nordenson. He, just as Piero Calamai, was a very skilled captain who had entered the sea-business in 1911, and became a captain in 1918. He had never been involved in any serious accident on his ships. His present ship, the Stockholm was a ship that differed from others on the North Atlantic. It was about half the size of the Andrea Doria and five knots slower. She was the smallest ship in the Swedish American Line. She had entered service in 1948 as a combined passenger- and cargo-ship. She only had two classes in which passengers travelled; first class and tourist class. On this voyage she carried 534 passengers (almost full, considering her 570-passenger-capacity), only 18 of them in first class.

As the two ships approached Nantucket, the weather was absolutely clear as far as the Stockholm was concerned. Coming from the other way, Captain Calamai was very well aware of the fog in which he steamed through. He and Nordenson was closing up on each other at two parallel courses, but was not aware of each other’s presence; the radar could not reach that far. Actually, it was not Nordenson on the bridge at this very moment. It was Johan-Ernst Carstens-Johannsen, or as his friends called him: Carstens. He was a young man of twenty-six, but very experienced for his age.

Suddenly, Carstens noticed a ship some one-and-a-half miles ahead and slightly to his port. He realised that the two ships would pass within one mile of each other, and Captain Nordenson had said that the distance should be at least one mile. So he ordered Stockholm to turn slightly to starboard in order to increase the distance.

On the Andrea Doria, Second Officer Curzio Francini discovered the Stockholm somewhat earlier due to their slightly more powerful radar. He alerted Captain Calamai, who saw that the approaching ship was almost dead ahead. The danger was not immediate, and the two men discussed on which side they would pass the other vessel. They decided to turn to port in order to avoid the ship.

Carstens could not believe what had just happened. The other ship was turning the same way he was. He ordered his ship hard to starboard, but maintained his speed.

On the Andrea Doria’s bridge, Captain Calamai was just as confused as Carstens, just a few minutes before. He turned his ship even more to port, but did not reduce the speed. The effect of having an unstable ship of 30,000 tons run at almost 22 knots at hard to port made the great ship skid towards the Stockholm. When Carstens saw this he ordered the engines put full astern, and maintained his course.

On such courses, the ships were doomed. When the Stockholm was almost put to a full stop, the Andrea Doria came skidding with her starboard side into Stockholm’s bow. The Swedish liner’s knife-sharp bow cut through Andrea Doria’s hull like it was made of butter. The Andrea Doria continued her 22-knot-race whilst the Stockholm stood still, badly damaged and very confused.

Immediately, Andrea Doria gained a twenty-degree list to starboard. Her engines were ordered to a halt, and Captain Calamai ordered the crew to uncover the lifeboats. That Andrea Doria was seriously damaged was quite obvious for the passengers and information to enter the boat deck for them was not required.

The combination of that the damage was in-between two different watertight compartments and the fact that the ship had such a large list to starboard sealed the Andrea Doria’s fate. Since the list very quickly entered twenty degrees and thereafter slowly, but steadily increased, the portside lifeboats were useless. Another contributing factor was that between the generator room and the fuel tanks, in two different compartments, there was no watertight door. Water rushed through the open tunnel and made the bulkhead useless. So there she was; one of the sisters that were the newest and safest in Italy’s hands, sinking with lifeboat accommodations insufficient for those onboard.

The Stockholm had also suffered badly from the collision. But she had been hit head-on, which is much better than to be hit on one’s side. The Stockholm’s damage did not quite reach her first watertight compartment, and as long as that held, she was not in any immediate danger.

The collision had taken place in a spot on Andrea Doria that had much passenger accommodation. Nearly fifty people were killed in the collision. One of those who miraculously were saved from this fate was Linda Morgan, a fourteen-year-old girl. She was thrown onto the Stockholm’s bow as it passed her bed, and remained on it when Stockholm tore herself loose from Andrea Doria’s hull. She was found by a crewman on the Stockholm who could speak Linda’s mother-tongue; Spanish, and that comforted her some before she could be rejoined to her somewhat reduced family. Her sister had died in the collision.

Captain Calamai still hoped that his ship could be towed to safety before it sank, but of course he sent for assistance. One of the ships that answered the call was the French liner Île de France. They hesitated at first, eager to remain on schedule, but soon set after the ill-fated liner. At 42,000 tons, the Île de France certainly had room to house extra passengers. Many other ships were on the scene when the Île de France arrived, among them the Stockholm who had sent out lifeboats to pick up the Andrea Doria’s passengers. All the passengers that were on the Andrea Doria, except for the ones that died in the collision were saved. In all, only 46 people perished.

Eleven hours after the collision had taken place, the Andrea Doria finally capsized and placed herself at some 250 feet depth. The Stockholm lowered her flag and blew her whistles to say goodbye. Captain Calamai had at first refused to leave his ship, but after some successful persuading from his officers with the assurance that all the passengers were safe, he finally agreed to step into a rescue boat. He spent the rest of his life in sorrow, as if he had lost a son, someone claimed. His last words before his death were: ‘Is everything all right? Are the passengers safe?’

The Stockholm was repaired in New York and resumed Atlantic service rather soon. Captain Gunnar Nordenson was given the privilege to command the Swedish White Viking Line’s new flagship, the 23,000-tonner Gripsholm. Johan-Ernst Carstens-Johannsen followed him as an officer. The Swedes were absolutely sure they had committed no wrong, and that is proved by this. But the Italian Line did not trust Captain Piero Calamai. He was never given the trust of commanding any of their ships anymore.

During the disaster hearings in New York neither the Andrea Doria nor the Stockholm was given the responsibility of the disaster, and since there never was a trial, no one has ever been blamed until this day.

Because the Andrea Doria is rather easy to reach, she has had visitors numerous times. Both welcomed visitors and others not so welcome. The wreck has been totally looted for many years. In 1995 Dr. Robert Ballard, the man who found the Titanic, went down to the sunken Andrea Doria in a nuclear-powered U-boat. The ship is wonderfully preserved, even better than the Britannic with her broken bow. Some parts of her superstructure such as the bridge has corroded away, but except for that and all the fishing nets draping her, she is the perfect shipwreck.

Specifications

- 700 feet (213.8 m) long

- 90 feet (27.5 m) wide

- 29,083 gross tons

- Steam turbines powering two propellers

- 23 knot service speed

- Passenger capacity of 1,221 people

Appendix

by Per-Ivar Andersson

As in most cases with ships involved in collisions, you can divide the course of event into two parts: first; how did the collision occur, and second; why did the ship or ships sink. Who is to blame for the collision? It is not an easy question to answer with certainty according to circumstances that appeared in the preliminary hearings beginning on September 19th.

In the preliminary hearings the Stockholm’s Third Officer Carstens-Johannsen was the first witness and was to be heard for a fourteen days of cross-examinations. When you are reading the report of the proceedings you are bound to make the impression that the representative of the Italian Line tried to use the fact that Mr Carstens-Johannsen was a relative young person for his rank, which he was, and according to his age he was rather inexperienced, which he was not.

The hearing showed him to have had some problems with the helmsman who had shown more interest for what happened around him than for the work at the helm. Because of that the officers in charge had to control him very often.

Then there was a verbal dispute if there was fog in the air or not. The Stockholm’s third officer did not admit there to be any fog at all around his ship and was given the question why he then was not able to see the lights from the Andrea Doria when the radar told him she was not even two nautical miles away.

Mr Carstens-Johannsen was to admit there might have been a spot of fog around the other ship, but at the time being he did not think this was the case because of the high speed of the other ship, which he had plotted on the radar.

The Italian Line’s representative then tried to prove the Stockholm to be approaching fog, the officer in charge must have been aware of this and therefore should have reduced the speed of his ship. Again the witness must explain the absence of fog around his ship. Furthermore he had to explain over and over again that the Stockholm could be brought to a complete stop in less than a nautical mile, and therefore he had waited until he could see the lights of the other ship before he changed his course.

Then he was yelled at and accused for being aware of finding the Andrea Doria straight ahead or even on his starboard bow. This caused a long dispute between the representatives of the companies before Mr Carstens-Johannsen denied the accuse.

All of his testimonies were confirmed of the other two men on the on the bridge and the man in the crow’s nest. They confirmed the absence of fog, the third officer had plotted the approach of the other ship and all of the three was absolutely sure they had seen the other ship to port before she had turned abeam of the bow of the Stockholm.

Then Captain Nordensson was to witness. On the third day he suddenly became ill and had a breakdown. He was sent to hospital for two weeks and a further four weeks for recovery for a minor brain thrombosis. None of the representatives had understood how completely exhausted the sixty-three year old captain was after having listened to the long hearings of his third officer and Captain Calamai of the Andrea Doria, not to mention all the heavy works in the evenings aboard the Stockholm, which was laying docked in Brooklyn.

After resuming his testimony he was immovable in his defence of Mr Carstens-Johannsen. Though, one weak point occurred under his witness. At first he ensured that his ship always reduced speed in case of fog. In accordance to the Stockholm’s logbook he was finally forced to admit that he had passed through fog in full speed in several occasions, but as Carstens-Johannsen had told earlier, Captain Nordensson had a full confidence in the Stockholm’s ‘enormous capability to come to a complete stop’, which allowed her to speed at 19 knots when fog sometimes was noted in the logbook.

When Captain Calamai was questioned, the Svenska Amerika Linjen’s representative soon came to the crux of the matter. He simply asked the Andrea Doria’s captain if he had any special training in radar techniques. He denied. Then he was asked if Second Officer Francini had any special training in radar techniques. He once again denied. Had any of the three officers on the bridge been plotting the radar observations of the approaching Stockholm? Captain Calamai thought it was not needed because it was a parallel course. Though, he admitted that the instructions ordered plotting, but the plotting table had not been used that evening, and was not commonly used because it was considered not necessary.

What had happened to the Andrea Doria logbooks was a most confusing matter. The only saved papers were the captain’s private logbook, two secret books regarding the N.A.T.O., all of the crews’ documents and a piece of the ship’s course-recorder. Though, the Italian Line’s office in New York had announced all the logbooks to be saved and had been sent to Genoa.

During a long interrogation Captain Calamai declared how the logbooks had been left on the sinking ship. He had given the order to save the logbooks but not to a particular officer. It was simply a matter of unclear orders where one officer took for granted another one should be obeying the order. Furthermore, neither the machine- nor the radiologbooks were saved. They had simply been forgotten when the order came to abandon the ship.

Time after time the questions of the logbooks were asked for during the cross examinations of Captain Calamai and the other officers of the Andrea Doria. Those books should have played a vital part when to reconstruct the course, positions and manoeuvres of the Italian ship before the collision. Because of this there could not be an answer to the final question: How could the radar show the Stockholm to be on the starboard bow of the Andrea Doria and the Andrea Doria on the port bow of the Stockholm? There are only two solutions to that problem; either one of the radars were incorrect or one of the men who observed the radars were misreading it.

Under the inquiry Captain Calamai made the silent admission that he at least partly was guilty for the collision, because he had had the command of a ship which had sailed through the fog at practically full speed.

The representative of the Swedish company showed a great interest in the stability of the Andrea Doria and what measures had been taken to save the ship after the collision. Captain Calamai showed a surprising lack of knowledge in questions relating to the stability of his ship. He answered one question after the other with ‘I don’t know’, or ‘I don’t remember’. He declared the Andrea Doria to be constructed in accordance to international regulations. The captain further admitted that he after the collision gave no instructions whatsoever to the engine room what to do to save the ship.

Finally, Captain Calamai showed several important distances and bearings where the Stockholm had been observed before the collision. According to this it showed up the course between the ships to be not parallel but clearly a collision-course, which Captain Calamai with silent voice had to admit.

Then he was shown another plot, based on the captain’s testimony, which clearly proved the distance between the two ships to decrease into a collision-course despite the four-degree-turn from the Andrea Doria for the purpose of increasing the distance. Captain Calamai was then asked if Second Officer Francini, who was observing the radar, had reported to him the decreasing distance to the other ship in spite of the Andrea Doria’s four-degree-turn and if he then should have continued without reducing speed. ‘No’, the captain answered, ‘I should immediately have stopped the engines, then gone full astern and possibly turned starboard after signalling for a starboard turn’.

Under Second Officer Francini’s testimony it appeared that plotting radar observations was not a custom in open waters under the command of Captain Calamai. If he had been plotting that evening he admitted he should have seen the Stockholm’s turn to starboard.

In the beginning of 1957 the case was withdrawn just before the Andrea Doria engineers should have been called as witnesses. Why?

The explanation was probably a report concerning the instructions of stability that was worked out for the Italian Line by the Ansaldo Shipyard. What the Swedish company’s lawyers found in this report has never been published.

On the other hand, a U.S. committee made a detached investigation regarding the collision and the investigation was published the same month. This committee announced among other things: The report shows the Andrea Doria to fulfil the regulations of the 1948 Convention of Safety for Shipping concerning the dividing up in watertight compartments with a very small margin. In ‘the stability report’ states the ship to be able to fulfil even the regulations of stability in the 1948 Convention provided that she was permanently ballasted with substantial and specified quantities of liquid in her different tanks. It seems impossible to explain the behaviour of the ship immediately after the collision on July 25th 1956 in no other way than with the assumption that she on this occasion was not ballasted in accordance with this instruction.’

When the bow of the Stockholm pierced just into the sections where the fuel tanks were placed, the Andrea Doria was doomed because of the absence of the ballast. The report of the committee stated the fact that the Andrea Doria probably only had one third of the stability her shipbuilders demanded. If the Andrea Doria had been correctly ballasted, she should not have received more than seven degrees of list or at worst fifteen degrees. Then the port lifeboats could have been used, or probably there would have been no use for them at all! It seems that Andrea Doria sank not because of the collision, but the ship not being sufficiently stable because of the lack of ballast.

What happened to the Stockholm? She was repaired at Bethlehem Steel Company Shipbuilding Division in Brooklyn N.Y. at a cost of 1,000,000 U.S. dollars and sailed for many years for the Svenska Amerika Linjen. After several voyages she was in 1960 sold to the D.D.R. and renamed Völkerfreundschaft. Then she was disposed off to Norway and became a floating hotel under the name of Fritiof Nansen. She lay rusting and finally she was sold as scrap to an Italian company. After a close inspection she was found in very good condition and appeared to be a very solid built ship except for the American-repaired bow and the company decided to restorate her and gave her the name of Italia Prima. She is today a cruising ship named Astoria and visited Sweden a few years ago.

2 thoughts on “Andrea Doria”

The photo of the lounge is NOT the Andrea Doria.

Best information ……Thank you