1840 – 1880

The very first ship to use steam as support on an Atlantic crossing was the American sailing ship Savannah who had been equipped with auxiliary steam engines geared to two paddle wheels on the ship’s sides. In 1819, she made the voyage between New Jersey and Liverpool in 27 days, but the ship had relied on her sails most of the time – the engine had only been running for 85 hours during the entire voyage. Not until 1831 did the Canadian paddle steamer Royal William cross the Atlantic with steam as the prime source of drift. However, her engines had to be stopped every few days because they had to be scraped from the accumulated salt deposits from the seawater used in her boilers. While the cleaning was being done, the Royal William depended on her sails. Finally, seven years later the new coastal steamer Sirius, temporarily hired for the trans-Atlantic voyage, made the whole voyage under continuous steam power.

Compared to sailing vessels, the new steam ships were not much faster. However, development accelerated faster and faster during this industrial revolution. Enthusiastic visionaries such as the British engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel realised that there was a future in the steam ships. In 1838, he commissioned the first of three magnificent sea-marvels – the Great Western. She was larger and faster than any ship before her and her interiors astonished the world.

At about the same time, the Briton Samuel Cunard too wanted to have a share of the trans-Atlantic passenger trade. He formed his Cunard Line in 1840 and that very same year he sailed on the Great Western back to England after a visit in America to see the first of four new liners commissioned by the him be launched on February 5th. The first of the new class was called Britannia. She started the tradition of how Cunard would name almost all of its ships in the future. All names would end with ‘-ia’ and they should be Latin words for different parts of the world. The three near-identical sisters of the Britannia (which of course means Britain) were Acadia (Nova Scotia), Caledonia (Scotland) and Columbia (America).

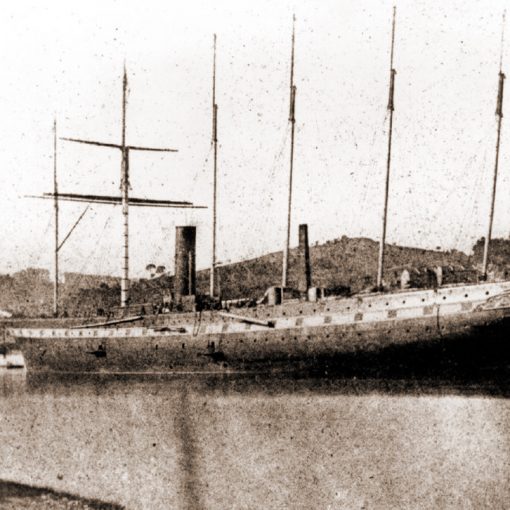

When completed, the Britannia looked every inch a sailing vessel with three masts carrying fully rigged square sails. Her bow was of the traditional clipper style and the squared stern boasted its gilded ornaments. But the two giant paddle wheels on the sides and the orange-red straight funnel between the first and the second mast proved Britannia to be something more than just another sailing vessel. With her – for the time – luxurious interiors, Britannia was a ship for the créme de la créme. Ordinary people who dared to go through an Atlantic crossing still used the ‘reliable’ sailing ships – or as they were commonly called ‘Coffin Ships’, because it was not seldom these vessels never arrived at their destination. The Britannia was what you could call the first of a new breed, offering a reliable service on a strictly regular schedule. Cunard had given the world the first true, purpose-built ocean liner.

In late June 1840, the Britannia arrived at Liverpool after the trip from her builders on the Clyde in Glasgow. The newspapers were not exactly hysterical about her as only two lines were spared for her in the local press at the day of her arrival. On Saturday, July 4th 1840 (Samuel Cunard’s birthday as well as the American day of independence), 63 passengers including Cunard himself along with his daughter embarked the Britannia who was to leave England on her maiden voyage towards Boston in the New World. The honour of being master on this very first voyage for any Cunard ship was given to Captain Henry Woodruff, RN. On July 17th, Britannia entered the harbour of Boston. The waiting crowds went wild with excitement as the new Cunarder berthed at the specifically designed ‘Cunard Wharf’. This voyage was considered by many distinguished Boston citizens as ‘the most significant crossing of the Atlantic since the Mayflower’. The time of crossing the Atlantic had been almost halved as the Cunard Line had entered the Atlantic with a bang, starting an era that would last for more than a hundred further years. The Britannia herself now settled into a distinguished career.

One of the most noteworthy moments in the Britannia’s history was in January 1842 when she carried the famous novelist Charles Dickens along with his wife Kate and their maid from England to America where he would attend a series of lectures he had been invited to. He was not the most experienced seaman so he chose the Britannia – one of the absolutely best ships on the oceans. But Dickens did not like the voyage at all. He found his cabin ‘claustrophobic’, and spent several days there before he recovered from his seasickness. He later wrote that he feared for his life when he saw the sparks from the funnel fly towards the hoisted sails. When Britannia reached America, Dickens did not leave the railing of the ship until she was securely moored to the berth. He returned to Europe by sailing ship, as the true – and now more dedicated – conservatist he was.

During an Arctic chill in January 1844, Boston harbour froze and trapped the Britannia who was just about to leave for Liverpool. Cunard Line’s reputation of reliability was threatened, but the citizens of Boston were obviously very emotionally attached to the ship as some of the city’s leading inhabitants put the money up to cut the ice up and free the liner. A seven-mile-long channel was made for Britannia through which she made a daring escape, thereby saving the Cunard Line’s splendid reputation, reaching Liverpool in time.

In September 1847, Britannia was stranded outside Cape Race. She was pulled away and repaired in New York. The next year she made her final crossing on her Liverpool-Boston route. The years after Cunard did not offer Britannia much more excitement. She was sold in 1849 to the German Confederation Navy and was renamed Barbarossa. In 1852 she was transferred to the Prussian Navy, bearing the same name. She continued to serve for the Prussians as an accommodation and guard ship, but they subsequently laid her up until 1880. Then the old ship was considered expendable and her last task was to serve for the navy as a target ship. In this guise she was sunk this same year. The beautiful Britannia – the pioneer of the famous Cunard Line – was no more.

Specifications

- 207 feet (63.2 m) long

- 34 feet (10.4 m) wide

- 1,139 gross tons

- Side lever engines powering two paddle wheels

- 9 knot service speed

- Passenger capacity of 115 people