1923 – 1956

Immediately after the First World War, the shipping lines of the world found themselves in a most difficult situation. All too many vessels had been requested by admiralties and as a consequence been destroyed during the hostilities. The British Cunard Line was one of the companies that had been very badly affected – after the war they had lost eleven passenger ships: The Lusitania, Carpathia, Franconia, Laconia, Ivernia, Ultonia, Alaunia, Andania, Aurania, Ausonia and the Asconia had all been victims of the enemy. The remaining Cunard fleet was not too impressive for the time, in all seven ships including the Aquitania and Mauretania.

The rebuilding of the fleet started with receiving war-prizes from the war’s losers. The Germans had to give up their entire big trio that the Hamburg Amerika Linie’s director Albert Ballin had created. The first of the trio – the Imperator – went to Cunard as replacement for the grand Lusitania, the second went to the Americans and the last and largest went to the White Star Line. Imperator was renamed Berengaria and started to serve alongside Aquitania and Mauretania.

However, Cunard realised that there were not enough ships to fetch from the Germans to update the reduced fleet. They had to build more ships, many more ships. In the late 1910s, the directors and design team of the Cunard Line presented their plans of replacement tonnage – in all fourteen new ships. These ships were to be small ones; there was no money for a ship to match the ‘Big Three’.

The first of these fourteen ships came in 1920. She was the Albania, and she was followed by three almost identical sisters – the Scythia, Samaria and Laconia. After these ships Cunard wanted to further perfect these small single stackers with two liners similar to the former four.

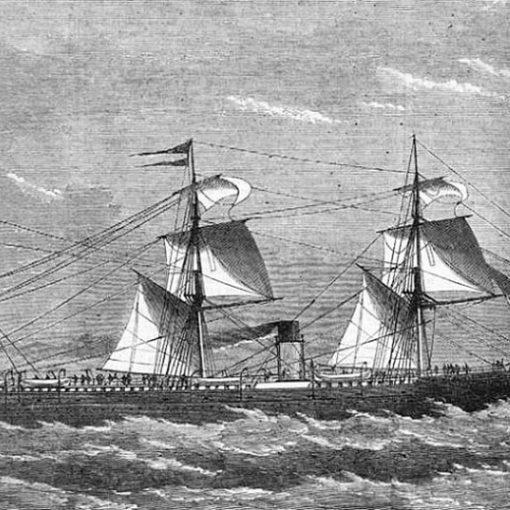

The first of these two ships was built by John Brown & Co., and designed by Leslie Peskett, head designer for Cunard, the same man that had designed the Aquitania – ‘The Ship Beautiful’. To honour the first Franconia that had been sunk during the war, Cunard decided to give this new ship that name. On October 21, 1922, Lady Royden, wife of Sir Thomas Royden, chairman of Cunard, launched the Franconiainto the River Clyde. On June 23, 1923, the Franconia successfully carried through her maiden voyage between Liverpool and New York.

It was now evident that the Franconia was by far superior to the four previous single stackers that had set her pattern. She was more luxurious, better decorated and had differences in design that the passengers seemed to favour. The interiors of the Franconia were fabulous. She had two garden lounges, a fifteenth-century styled smoking room, a health centre and a racquetball court.

During the Twenties, the Franconia was much used for cruising – something the shipping companies more and more had to rely on. Loyal passengers on board the Franconia were celebrities such as Cole Porter, Noël Coward, Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein.

The Franconia seemed to be every inch a ship for people who wanted to leave their troubles behind and relax for some time, but she ship was certainly not immune to accidents. On April 10th, 1926, the Franconia was involved in a collision between her, an Italian gunboat and a Japanese vessel in Shanghai harbour. The Franconia had intended to leave her wharf, but run aground with her bow, making her stern swing around into the two smaller vessels. To make matters worse, a buoy became tangled in the Franconia’s propellers. This resulted in the sinking of a small lighter and the killing of four of its crewmembers.

Despite this tragic accident, the Franconia remained a very popular ship who continued on the Liverpool-New York route on the summers and as a cruise ship in the winter months. She continued this scheduled service until the outbreak of World War II in 1939.

In September of 1939, as Adolf Hitler marched into Poland, the Franconia was repainted grey and turned into a troopship capable of carrying 3,000 soldiers. She was immediately employed in the Mediterranean. On October 5 the same year she collided with the Royal Mail Line’s Alcantra who was serving as a troopship for the British as well. This event did not go of well, as Franconia suffered serious damage and had to go to Malta for extensive repairs. The following June, the Franconia was hit by Axis bombers while in service west of France when she was carrying 8,000 troops. The safety policy of Cunard paid off, as the Franconia remained afloat and saved the lives of thousands of people.

For the remaining years of the war, the Franconia continued as a troop ship, going to India and the Middle East via Cape Town and taking part of the invasions in Madagascar, North Africa and Italy. During 1944 she carried American troops to the Mediterranean.

Proven a very sturdy and reliable ship, the Franconia was given a very honourable task in 1945. Top secret orders from above ordered the Cunarder to the Mediterranean after she had some of her luxury fittings taken from storage and re-installed. When in the Mediterranean, the Franconia was sent further on into the Black Sea where she would serve as the floating headquarters for the British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and his staff during the historical Yalta Conference. Prime Minister Churchill was given a series of suites, while the staff; including secretaries, telegraphers, typists, and security guards – in all over a hundred people – joined him in less ornate environments. Cunard knew how to treat Churchill and since he liked spending much time in the bathtub, they installed a shelf just next to the tub, offering the Prime Minister to work and enjoy a good soak at the same time.

When the devastating war finally was over in 1945, the Franconia completed some voyages across the Atlantic with refugee and emigrants. She had covered 319,784 miles in Government service carrying 189,239 military personnel all together. In 1949, she was handed back to Cunard who fully restored her into her pre-war glory. The notable thing about the emerging of the post-war Franconia was the fact that her passenger capacity had been considerably reduced – from 1,843 to 853. From now on she was put on the Canadian service, from Liverpool to Québec via Greenock.

The last major accident the Franconia suffered occurred on July 14, 1950. While just a mile off Québec City the ageing ship’s steering gear failed and she went aground. The vessel did not seem to move on its own power, so all the passengers were taken off and sent to nearby hotels. In order to lighten the ship, all excessive weight were removed. Eventually, it took a team of tugs and four days to set the Franconia free. She then set off back to Québec where temporary repairs were made, and then crossed the Atlantic to Liverpool where complete repairs were carried out.

Until 1956, Cunard employed Franconia as a passenger ship. Then, she was considered too old and her last voyage was scheduled to that October. She crossed to New York without major flaws, but on the return voyage she was plagued with mechanical faults. Upon return to Britain, the Government intended to employ the Franconia as a troopship going to Suez, but when they learned about the fiasco return voyage, they abandoned this project. Instead, Franconia was sold to the British Steel & Iron Corporation who received the old vessel in late December 1956 and broke her up at Inverkeithing.

Specifications

- 623 feet (192.8 m) long

- 73 feet (22.6 m) wide

- 20,158 gross tons

- Steam turbines powering two propellers

- 16.5 knot service speed

- Passenger capacity of 1,843 people

6 thoughts on “Franconia (II)”

My Mother was on the Fraconia for her trip back home to see her family.

Mom was a war bride who married a handsome Canadian soldier in 1941.

In 1942 war brides were being sent to safety of the British colonies.

She was on the Franconia when it ran aground in the St. Lawrence.

She sprained her ankle when on the netting climbing down the side of the ship.

Happing ending as Mom got to England and had a great visit with her Mon, Dad and Siblings.

The Francoia had an honorable record …Well Done

.

I was 8 years old when we travelled from NYC to Southampton (Im sure it was Southampton), my parents plus 4 of us young children on the Franconia. I have wonderful memories in my beautiful little dress and shoes fine dining in the dining room and wonderful waiters. I have no knowledge of delays……

My father-in-law was but 13 years old when he and his mother booked passage on the Franconia in July 1950 from Quebec City to Ireland. This of course was the Ill fated grounding incident. As Kevin recalls, tug boats were dispatched to take the passengers to nearby hotels after unsuccessfully navigating their way out of the St. Lawrence seaway before running aground on an island. Rumour among the passengers was that the ships pilot was intoxicated rather than the steering system failing. As it took 4 days to extract the ship and it also required repairs, they were afforded a flight which landed in Paris in lieu of continued ship passage. Ironically the plane experienced mechanical issues and they overnighted in Paris until they could get a flight to Dublin. Needless to say an adventure that he remembered vividly.

She was plagued with mechanical troubles even earlier than mentioned in the article. I sailed on her from Southampton in April of 1956 and her engines stopped in the mid-Atlantic. We drifted for 4 days, until she was repaired and completed her voyage. Regardless she was such a fine ship and I loved her dearly. The weather was very fair and I spent most of my days outside at the stern watching the ocean and the white turbulence from the screws. That journey was such a pleasant experience, I wish somehow by magic she would re-appear from the dead and I could do it all over again.

We were among the passengers on her last trip to NYC. It was a cold and blustery November. The trip was “plagued” by mechanical problems, including engine failures. We limped into NYC harbor nearly a week after we were to have docked. I was very young, but my siblings recall how the trip was so rough that even the captain was sick. I’m sure this helps explain my reluctance to ever take a cruise vacation.

I am researching my fathers Royal Navy service history; John Devine service no. J33658 . On 26th September 1941 there was an ammunition explosion on the troopship SS Franconia while docked at Liverpool. My father John Devine rated AB serving as a Royal Navy DEMS gunner GL2 was seriously injured in the explosion. I have discovered that (Sir)Peter Markham Scott was on board and reported extensively on the incident. He was noted as among others who distinguished themselves by taking quick action to limit further damage and loss of life.

I would be very grateful anyone can provide any further information available about this incident relating by name to my father and the extent of injuries to others involved. I have been unable to trace a ships log entry or find a crew list for SS Franconia naming my father who may have been obliged to sign on as a merchant seaman.

Many Thanks John Devine (Son)