1960 – 1980

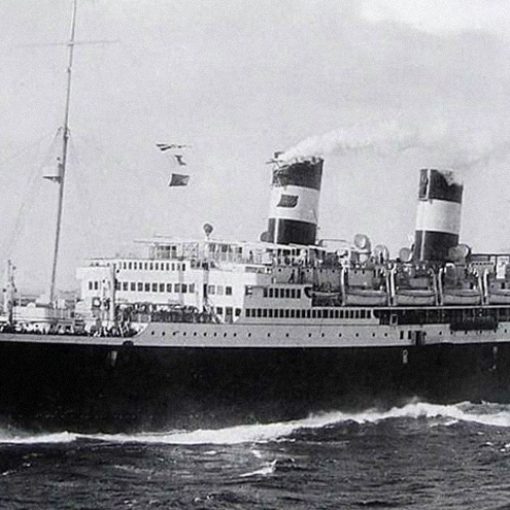

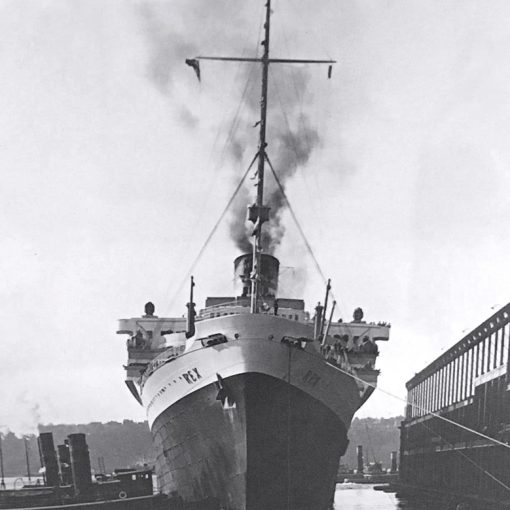

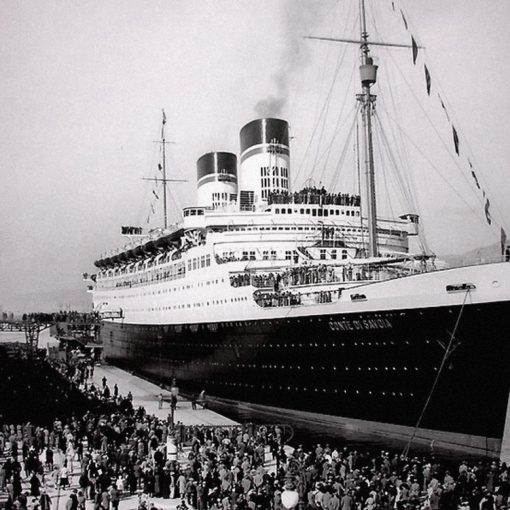

After the Second World War, the Italia Line found themselves in a most precarious situation. Both their prime liners – Rex and Conte di Savoia – had become victims of the war. The company rebuild its fleet with smaller liners, but as the 1950s were closing they felt that a new set of large ships would do the trick of financial prosperity for the Italia Line. In 1953 the first of two sisters was commissioned. Her name was Andrea Doria and was the answer to many Italians’ prayers. At almost 30,000 gross tons, this ship was not the largest built in Italy, but by all means the most beautiful and advanced. Her speed could not match that of her predecessors Rex and Conte di Savoia, but nevertheless there was something special indeed about Andrea Doria. She was followed the next year by her almost identical sister – the Cristoforo Colombo. These two liners gave Italy the honour of operating the finest ships in service in the Mediterranean.

The most devastating blow to the Italia Line occurred in July 1956. As the Andrea Doria was approaching New York harbour, another liner was just beginning its eastbound voyage towards Göteborg, Sweden. The ship’s name was Stockholm, and she was run by the Swedish American Line. In the foggy night the ships collided, mortally wounding the Italian ship. The day after the Andrea Doria rolled over onto her side and sank beneath the waves. She took some fifty passengers with her to the ocean floor. The Stockholm stayed afloat and managed to rescue a great part of the Andrea Doria’s passengers. Both the Italia Line and the Swedish America Line tried to sue the other company, but endless court proceeding only resulted in that no one could be blamed for the accident. However, evidence showed that Andrea Doria’s commanding officer Captain Calamai lacked enormously about the knowledge of his vessel and modern routines. He was never given the trust of commanding any other ship for the Italia Line, whereas Captain Nordenson of the Stockholm was given the honour of commanding the brand new Swedish America Line flagship Gripsholm a few years later.

Suddenly, the Italia Line again lacked a prime ship on the North Atlantic. While one third of the company’s board sat through the tedious court hearings regarding the Andrea Doria, and another third handled the existing trans-Atlantic service, the last third planned for a replacement for the lost liner. The construction of the third Andrea Doria-class liner started in early 1958. Keeping with Italia Line’s tradition of naming their ships after famous Italians, the new vessel was to be named Leonardo da Vinci. After meticulous construction by the Ansaldo Shipyards in Genoa, the latest addition to the Italian merchant fleet was launched and christened by the Italian president’s wife Signora Carla Gronchi on December 7th, 1958.

The design of the Leonardo da Vinci was based upon those of the Andrea Doria and Cristoforo Colombo, but the improvements were many. For example, the after deck area had been freed from cargo cranes and such, leaving an unobstructed lido area with six swimming pools for the passengers to enjoy. The one reserved for the first class passengers was heated with infrared rays. The private plumbing had been increased up to eighty per cent in tourist class. Added to all this, the ship’s machinery was said to be easily converted into nuclear power. The Leonardo da Vinci was indeed a ship of a new time. Her maiden voyage occurred in July 1960, with spraying fire boats, tugs and helicopters escorting her into New York harbour when she arrived in the New World. A welcome party was held for the ship, including pierside fêtes, elegant luncheons and an open house for the public. The Italia Line finally felt that the wounds after the Andrea Doria-disaster were healing.

But it was not all glory for the Leonardo da Vinci. She had proved to be very unstable, just like her sisters, and she had to be filled with some 3,000 tons of iron along her bottom to stabilise her. This meant that she was too heavy for her engines and this resulted in very expensive fuel costs. She actually turned out to be the most expensive liner the Italia Line had ever run.

As the 1960s advanced, it became more and more evident for the shipping lines that their liners were becoming obsolete due to the new long distance airliners that had begun to fly between the continents. The Leonardo da Vinci – like so many other liners of the time – was sent off cruising. Her hull was painted entirely white in 1966 when she was almost solely dedicated to the cruise trade, being replaced on the North Atlantic by the new Michelangelo and Raffaello. The Leonardo da Vinci’s ports of call during her cruise voyages were among others Palma, Messina, Palermo, Barcelona, Casablanca, Lisbon, Madeira and Las Palmas. Sometimes she was employed in the Caribbean and South American cruise service. One of her most wonderful long cruises ever was when she in February 1970 set out on a forty-one-day cruise to Hawaii via the Panama Canal.

In June 1976 the Leonardo da Vinci ended her trans-Atlantic service once and for all. She was not required in the cruise business for the time either, so she lay idle until July 1977, when she was reactivated by the newly formed Italia Line Cruises International who aimed at Miami-Nassau overnight cruises. The managers of this new company were another famous Italian company – the Costa Line. However, the Leonardo da Vinci proved far too large and expensive for this kind of service. Sadly, she was rejected after some time and was sent to be laid up at La Spezia, all to close to the infamous scrapping firm nearby. Rumours started about her being sent back into cruise service or about a renewed luxury liner service from New York. The most interesting was the idea of having her permanently moored in the River Thames in London as a casino ship. None of these rumours proved to be true, and the Leonardo da Vinci continued being laid up.

Seven months into the 1980s, on July 4th, the Leonardo da Vinci suffered a mysterious fire while at anchor at La Spezia. The raging blaze lasted for four days leaving an empty, devastated shell of the once so luxurious liner. The ship had capsized and was towed with a sixty-degree list out of the main harbour where she was righted. Everyone realised that there was nothing to do and the Leonardo da Vinci was towed to the nearby scrapyard where she was cut up. She was bought for $1,000,000 only, an extremely low price, considering her insurance value of $7,000,000. Yet another of the world’s beautiful liners had been wasted and was no more.

Specifications

- 761 feet (232.6 m) long

- 92 feet (28.1 m) wide

- 33,340 gross tons

- Steam turbines powering two propellers

- 23 knot service speed

- Passenger capacity of 1,326 people