1948 – Present Day

Also known as Völkerfreundschaft, Volker, Italia, Italia Prima, Valtur Prima, Caribe, Athena, Azores, and Astoria

On December 11th 1915, the recently founded Swedish American Line started its activity on the North Atlantic with the maiden voyage of their first ship Stockholm, formerly the Holland-Amerika liner Potsdam. The company was the brainchild of Wilhelm R. Lundgren, who had seen the profitable possibilities of a Swedish transatlantic shipping line. Sweden had so far witnessed a massive emigration to the Americas, but so far they had been forced to travel via England to reach their destination. The voyage was not an easy one, not least because of language-barriers between the Swedes and the crewmembers on board the ships they were travelling with.

However, Lundgren realised that a Swedish transatlantic line would erase these problems. The passengers would travel directly between Göteborg and New York, and with an all-Swedish crew, there would be no language difficulties. But the Swedish America Line was too late to earn their share of the emigration. On the company’s eighth year, Sweden saw the last wave of emigration. The company would have to find a new clientele soon.

And so they did. Their new passengers became the tourists. Instead of people seeking fortune in America, SAL now carried them and their relatives still living in Sweden between the continents for short visits. By the end of the 1920s, SAL was already setting their sights for the growing cruise industry. The two new ships Gripsholm and Kungsholm set a trend that the Swedish America Line would follow until its final days: Ships of great comfort and decoration.

The company continued their activity through the 1930s and established itself as one of the prime cruising lines of the world. Business was booming and the company soon decided to place an order for what would be their largest ship so far – a new Stockholm, with a projected size of some 30,000 tons. The shipyard to build it was the Monfalcone shipyard in Italy. But two years later, in December 1938, the almost finished Stockholm caught fire and sustained heavy damage. However, the shipyard did not give up and started rebuilding the Stockholm almost from scratch.

Then, in 1939, World War II became a fact and brought ordinary life to a sudden halt. As with many other shipping companies, SAL was forced to contribute with their ships. The Gripsholm and Drottningholm served as repatriation ships for the Red Cross. In March 1940, when Europe had been at war for seven months, the new Stockholm was launched in Italy. But with the war raging on, the Swedish America Line had no interest in receiving her. However, Italy was in need of ships and purchased the Stockholm and renamed her Sabaudia. She served Italy as a trooper but was sunk at the end of the war.

When peace was finally achieved after six years of bloody fighting, SAL was in need of a new ship. But the board of the company was faced with a problem. The first thought was too build a ship similar the company’s old successful ones. But with aeroplane travel growing rapidly, it might be wiser to build a smaller vessel with less passenger capacity. In spite of protest from the chief executive officer and the American part of the company, it was decided that a smaller ship was to be built.

The task of building the new ship was given to the Götaverken shipyards in Göteborg. But from the very start of her construction, the new ship suffered from bad luck. Due to union strikes, the laying of her keel was delayed by several months. When the day to launch her finally came, on September 9th 1946, it took several tense minutes before she started her journey towards her rightful element. For some, it was indeed a bad omen.

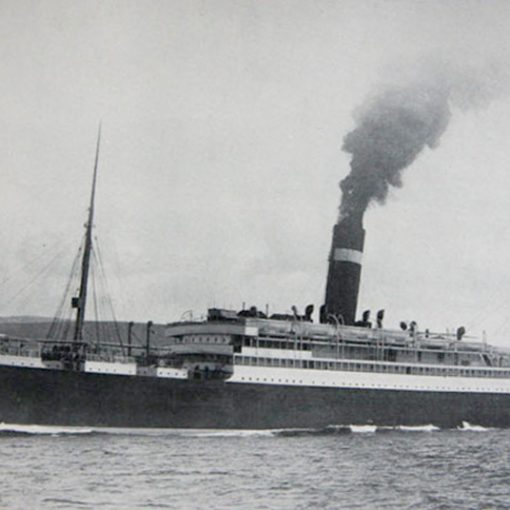

When the Stockholm was finally completed, it was apparent that she differed from the line’s earlier vessels in many ways. The Swedish America Line had established a reputation of operating ships with luxurious decorations and spacious passenger accommodations. The new Stockholm did not have any of those. Although she was the largest ship so far built in Sweden, she was a small ship in the company’s fleet. Indeed, with her 12,165 tons she was the smallest liner operating on the North Atlantic run, with a passenger capacity of no more than 395 people. Her small tonnage was very much apparent when you looked at her interiors. The large public spaces that had been something of a trademark on SAL’s other ships could not be found on the Stockholm. All of her saloons and public rooms were no doubt comfortable, but they were not comparable to those on SAL’s old ‘floating palaces’.

The low passenger capacity and the small public spaces made the Swedish America Line market their new vessel as ‘a different ship’, built ‘for comfort rather than luxury’. But the American branch of the line did not welcome the new ship with warm feelings. With her not so impressing size in mind, they did not foresee a grand future for her on the American cruise market. Nevertheless, the third Stockholm also had her good qualities. Her exterior design was sleek, resembling a yacht, and in some aspects even a navy destroyer. The slanted bow gave her a speedy look, although her service speed was only 17 knots. She was painted in the Swedish America Line’s traditional colours; a white hull and a light-yellow funnel with a blue shield adorned with three golden crowns. Internally, she had a new feature. When design her staterooms and crew-quarters, it was done so that all were located along the sides of the hull. By doing so, all rooms had access to daylight and a view of the sea through at least one porthole. This was, according to the ship’s crew, ‘a revolution on the Atlantic’.

On February 21st 1948, it was time for the Stockholm to set out on her premiere voyage. It had been much delayed, and the North Atlantic soon reminded people that February is not the most ideal month to cross her. The Stockholm encountered heavy winter storms and suffered from severe rolling in the rough seas. The twists and rolls of the ship were very unpredictable, and a passenger was killed in the storm. The Stockholm’s rotten luck continued. Soon, the Stockholm was known as one of the worst ‘rollers’ on the North Atlantic. This was of course bad publicity, so the Swedish America Line took her in to remedy her instability. Cargo holds that was intended for express goods was filled with 3,000 tons of stone to give her some more weight in the keel. Unfortunately, the problem was not lightness, but a bottom simply not suited for the North Atlantic. The stones now occupying precious cargo-space did not do things much better.

The misfit of the Swedish America Line continued her service with the company, and in 1953 she was taken in for a refit. The ship’s superstructure was enlarged to include more passenger cabins and a cinema theatre. Her passenger capacity was thereby increased to 548 people. Three years later, in the first half of 1956, Stockholm was fitted with stabilisers, and finally her rolling motion was partially tamed. But even now she could not count as a very well known ship on the North Atlantic. However, an event that would change that lay in her future.

On July 25th 1956 shortly before noon, the Stockholm slipped her moorings in New York harbour to depart on her 103rd eastbound crossing with Göteborg as final destination. Commanding her was Captain Gunnar Nordensson, whose experience in ships and the sea went back to 1911 when he first joined the business. Later that night, at 10.30 p.m., as the Stockholm was approaching Nantucket, another ship was coming in from the other direction – the Italia Line’s Andrea Doria. Commanding the bridge of the Stockholm was third officer Johan-Ernst Carstens Johannsen. At the age of 26, he was already an experienced seaman, having been to sea for more than ten years already.

As his ship was travelling through Nantucket’s waters, the weather was clear. In front of them lay a bank of fog, through which the Andrea Doria was now steaming at high speed. On the bridge of the Italian ship, second officer Curzio Francini had already noted on his radar that a ship was in front of him. It took a few minutes before Carstens made the same discovery on the Stockholm, as she had a slightly less powerful radar. Carstens noted that the meeting vessel, whose identity he still knew nothing of, was 12 nautical miles in front of him and on his port side. When the distance had shrunk to 10 miles, Carstens went to the plotting table and plotted the approaching ship’s course. He came to the conclusion that she was two degrees to the port of his ship. But the lookouts could not see any lights in front of the Stockholm. Nevertheless, Carstens prepared his ship to pass on the starboard side of the Andrea Doria by making a slight turn to starboard.

On the fog-surrounded Andrea Doria, things were a little different. The crew on her bridge interpreted the radar echoes as the Stockholm was four degrees on their starboard bow. When the distance between the two ships was about four miles, Captain Piero Calamai on the Andrea Doria ordered his ship four degrees to the port to give them a little more safety space. He did this in spite of international rules that proclaimed that when two ships meet they should do so on the starboard side of each other. The two ships did not yet have visual contact when the distance between them was as little as two nautical miles.

On the bridge of the Stockholm, Carstens could not believe what he saw. The other ship was turning the same way he was. He ordered his ship hard to starboard, maintaining his speed of about 18 knots. On the Andrea Doria’s bridge, Captain Calamai was just as confused as Carstens on the Stockholm’s bridge. Still believing that Stockholm was on his starboard side, he ordered his ship hard to port, but did not divert from his speed of 22 knots. By doing so, he caused his ship of 30,000 tons to skid towards the Stockholm. When Carstens saw this he ordered his engines full astern and turned to starboard. He then ordered the watertight doors closed.

The Stockholm was slowing down at the same time as the Andrea Doria came skidding out of the fog towards her at high speed. Collision was inevitable. The Stockholm’s bow, reinforced for the sometimes icy Scandinavian waters, sliced through the hull of the Italia Line’s pride and joy on her starboard side, just abaft of and below the bridge. The Stockholm then fell back, exposing her now badly crumbled bow and the massive hole in the Andrea Doria’s side. The Italian ship continued at her high speed, but then came to a stop at a distance of about one mile from the Stockholm. After only a few minutes, the Andrea Doria had taken on a 20-degree list to starboard.

The first order of business on the Stockholm was of course to sound the ship. She had already sunk three feet at the head and taken on a list of four degrees. When inspecting the twisted bow, it was discovered that five crewmen had been killed instantly when the impact came, and several more were trapped in the wreckage. When it was clear that the Stockholm was in no immediate danger, her lifeboats were launched to rescue people from the sinking Andrea Doria.

What followed must be one of the most dramatic rescue-operations at sea ever. In addition to the Stockholm’s lifeboats, many other crafts came to the rescue, among them the magnificent French liner Île de France and the Cape Ann. Thanks to this, the only people that died in the disaster were those who perished as a cause of the violent collision, in all 46 people. After eleven electrifying hours since the collision, the Andrea Doria rolled over and sank. The Stockholm, which in addition of her own 534 passengers was now carrying 327 passengers and 245 crewmembers from the lost Italian liner, blew her whistles and slowly started her return to New York.

The voyage to New York harbour became a prolonged tension for all on board the Swedish liner. With the bow badly twisted and crumbled, the forward watertight bulkhead was now the only thing keeping water out. Should it give away during the voyage, it could be a new disaster immediately. The Stockholm was carrying 1,319 people, but had room in her lifeboats for only 846. With this in mind, she was escorted by the Tamaroa and the Owasco, but if something would happen, these two ships had now possibility of taking on board all the people from the Stockholm. Luckily, the sturdy Stockholm stood up to the test brilliantly, in spite of her no longer existing bow. On the way back she averaged 8.4 knots, and although the forward bulkhead was taking on great strain, it held together all the way back to New York.

When the Stockholm arrived at the Swedish America Line’s pier 97 in New York harbour, a large crowd of people had gathered to see the damaged liner. Policemen were there to hold them back, and numerous media representatives had also gathered on the docks. The first people to disembark from the Stockholm were those saved from the Andrea Doria. The Swedish America Line now had to repair the Stockholm and put her back into service quickly, before her absence could accumulate too great losses in profit. Her next three transatlantic crossings and a cruise were cancelled, as she was in apparent need of a new bow. She was hardly in condition to return to Sweden for these repairs, and so the task was given to Bethlehem Steel Company Shipbuilding Division in New York. On July 28th, three tugs towed her from pier 97 to the place where she would be given a new bow. The work cost the Swedish America Line $1,000,000 and after about three months she was again ready for service.

After the hearings had been conducted in New York, and a settlement had been reached between the two shipping companies, the Stockholm continued serving the Swedish America Line. But she was still the misfit of the fleet and could not offer the high standard available on the company’s other ships. In 1954, the company had ordered a new Gripsholm from the Ansaldo Shipyards in Genoa, Italy – the same company that had once built the Andrea Doria. After some delays, the new Gripsholm was delivered to SAL in 1957. A new Kungsholm had been delivered from the Dutch yard of de Schelde in 1954, and with these two new ships in service, SAL could try to get rid of the Stockholm. After several failed attempts, the East German government emerged as a possible buyer and on January 3rd 1960, the Stockholm was sold after only 12 years of service in the Swedish America Line’s fleet. She was renamed Völkerfreundschaft. She kept her bonds with Sweden though, as she was sometimes chartered to the Swedish Stena Line for cruises from Göteborg.

After 25 years in East German communist service, the Völkerfreundschaft no longer made any profits. In 1985, she was sold to the Panamanian company Neptunas Rex Enterprises, who shortened her name to just Volker. She spent the rest of the year laid up in Southampton and was then towed to Oslo in Norway to serve as a barracks ship under the name Fridtjof Nansen, providing shelter for asylum seeking refugees.

In 1989 she was sold to the Italian company Star Lauro, situated in Naples. She was towed to Genoa to be given an extensive refit. Upon her arrival there, she was given a chilly welcome by the press. The Italians had not forgotten that this was the ship that sunk their pride Andrea Doria some 30 years ago. In 1992 the work of refitting the former Stockholm began. It was discovered that the Swedish-built liner was in a very good condition, except for the American-built replacement bow, which needed the most refurbishing. After suggestions of giving her names as Surriento or Positano, the old Stockholm emerged as the Italia in 1993, but was sold again the following year. Her new owners, Nina Cia. di Navigazione, decided to completely gut her and use the sturdy hull as the foundation for a completely new ship – the Italia Prima at 15,200 tons. Beginning in 1998, she was then employed cruising in the Caribbean.

In November 1999, the ship was chartered to a Rome-based Italian operator called Club Valtur. The ship was renamed Valtur Prima, and was kept on her West Indies itinerary, with Cuba as her specialty. This operation was successful, but after two years the situation would change dramatically. With the terrorist attacks on September 11th 2001, the global situation was greatly affected. This forced Club Valtur to cancel their sailings. Valtur Prima was laid up at Havana, awaiting an uncertain future. But the former Stockholm once again found employment, when she was chartered on a five-year basis to Festival Cruises. However, the plans for the ship doing 7-day cruises out of Havana under the name Caribe failed to generate much profit, and she was laid up in Havana before being transferred to Lisbon, in Portugal. In 2004 she was sold to the Portuguese company Nina SpA, and moved to the Portuguese registry. In January 2005 the ship was once again renamed, this time Athena, and employed for Classic International Cruises on such varied itineraries as the Baltic, the Adriatic & Ionian Islands and New England/Canada.

On December 3rd 2008, the Athena again experienced drama when she was attacked by pirates in the Gulf of Aden. Surrounded by over twenty smaller craft, the ship’s crew managed to keep the attackers from boarding by using high-pressure water cannons against them. Fortunately, the pirates gave up their attack, and the Athena could continue her voyage without any damage or injuries.

In 2013, the former Stockholm once again found herself under a new name. Sold to the newly-formed Portuscale Cruises, she was renamed Azores, and was sent to Marseilles for a refit. For a few years, she continued to offer European cruises, but in 2015 she would yet again be transferred to another company. Sporting yet a new name on her bow – Astoria – she entered service with Cruise & Maritime Voyages. Hopefully, this distinguished lady will be with us for some time yet.

Specifications

- 525 feet (160.4 m) long

- 69 feet (21 m) wide

- 12,165 gross tons

- Götaverken diesel engines turning two propellers

- 17 knot service speed

- Passenger capacity of 395 people as originally built, increased to 548 people during 1953 refit

5 thoughts on “Stockholm (III)”

Unfortunately the Astoria was sold in June 2025 for 200,000 euros to a scrapping company based in Belgium. On 4 July she arrived in Ghent for ‘recycling’. The end of a 77 year career. Such a shame to see her go.

she is still in Rotterdam

The liner is now in a Ghent scrapyard.

Does anyone know the current status of the MS Astoria? The last information I heard was that she was towed from Tilbury (UK) to The Netherlands (Rotterdam or Amsterdam). There is no record of her leaving.

she is still in Rotterdam