1903 – 1918

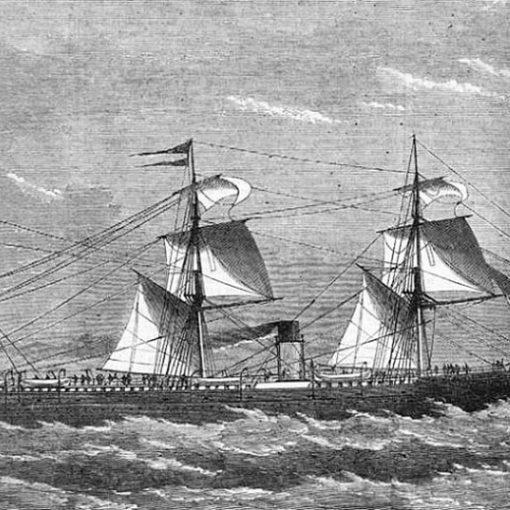

In the beginning of 1902, an excavation was well under way in the Wallsend Shipyard of C.S. Swan and Hunter Ltd. At the same time as the archaeologists had uncovered the eastern end of Hadrian’s Wall, a new liner was taking shape at one of the yard’s gantries. With her keel laid down on September 10th1901, this new Cunarder was launched on August 6th 1902. Her name was the R.M.S. Carpathia.

When completed, the Carpathia would actually become one of the Cunard Line’s largest ships to date. However, she was not intended as a very luxurious liner. Where bigger ships would carry the wealthy passengers, Carpathia had accomodations only for second- and third-class passengers in addition to her other objective; to carry refrigerated food. For this purpose, she was equipped with three refrigerating engines plus an additional one for her own provisions. Her machinery consisted of two quadruple expansion engines which turned her two propellers, giving the liner a top speed of about 14 knots. When finished, the Carpathia could carry about 1,700 people – 200 in second class and 1,500 in steerage. The standard was high for her day. Third class included a smoking room, a bar, a ladies’ sitting room and a big dining saloon capable of serving 300 people at a time. The dining room in second class could seat 200; all the passengers in second class should the ship be loaded to capacity. Other than all the amenities mentioned above, second class also housed a library.

Because her completion was delayed by a strike, the Carpathia’s maiden voyage didn’t take place until 1903. On May 5th, she left Liverpool, bound for Boston. Having proved to live up to her owners’ expectations, she soon became well acquainted with the swell of the North Atlantic.

The Carpathia continued to serve her owners well over the years, but she never received any special attention. This is understandable, since the battle for the Blue Riband was fought by the elite steamers such as the Lusitania, Mauretania and the Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse. Soon, however, the world’s attention would turn on the Carpathia, literally, overnight.

On the night between the 14th and 15th of April 1912 her wireless-operator at the time, Thomas Cottam, received that now-famous message from the stricken Titanic:

‘Come at once. We have struck an iceberg. Latitude 41.46 North, Longitude 50.14 West.’

Cottam quickly reported this message to his captain, Arthur Rostron. Having no doubt, Rostron immediately ordered the ship turned around, at the time being bound for the Mediterranean. That night, Carpathia proved to be reliable. Pressing every ounce of steam into the engines, she managed to exceed 17 knots, well passing her predicted top speed. Despite this, it took the little Cunarder about four hours to reach the Titanic’s reported position. By this time it was too late. All that could be done now was to pick up the survivors, in all about just 700 people. About 1,500 souls were lost.

Shortly before 9 a.m. on Monday morning, April 15th, Captain Rostron ordered his ship to head for New York. Arriving there in the evening of April 18th, she berthed at Cunard’s pier 54 and the Titanic’s survivors disembarked. Thousands of people lined the docks to get a glimpse, and newspaper reporters tried to board the ship in search of a ‘scoop’.

Two days later, on April 20th, the Carpathia again left New York to complete her unfinished voyage to the Mediterranean. Now, everyone knew of this heroic ship, and her captain was equally famous. Rostron left the Carpathia to command the great Mauretania in 1915. He stayed with her until 1926, and was later appointed commodore of the Cunard Line. He died in 1940.

The Capathia’s fate, however, came a little sooner. During the first world war, Captain William Prothero was given her command in 1916. Still serving on the North Atlantic, the Carpathia had avoided disaster a few times by escaping successfully from submarine-attacks.

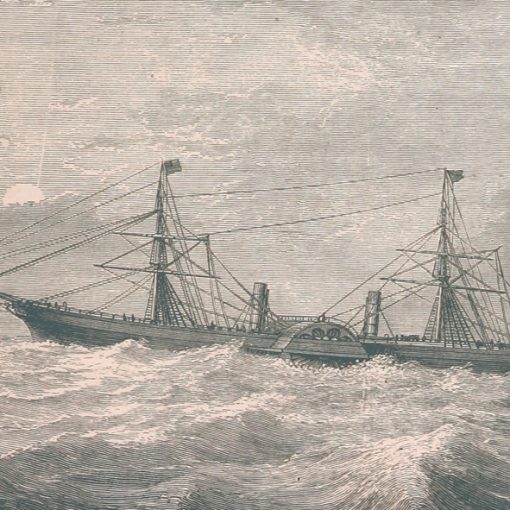

On the 15th of July 1918, she left Liverpool bound for Boston, just as she had done 15 years earlier on her maiden voyage. Being part of a convoy of several ships, she travelled at a zig-zag course along with an escort. Early on Wednesday morning, July 17th, the escort left the convoy, which then split up in two. The Carpathia continued west along with six other ships as commodore ship, her being the largest one.

Three and a half hour later, the menacing track of a torpedo was seen bearing down on the ship’s port side. The helm was put hard-a-starboard and the port engine was put full astern. But it was too late. The torpedo struck on the port side, between the No. 4 hold and the stoke hold below the bridge. Just seconds later, another torpedo hit the ship in the engine room, thus disabling her ability to escape. In the explosion, five firemen were killed, and the two engineers were seriously injured. In addition, the explosion wrecked all the electrical gear, including the wireless, as well as two of the ship’s lifeboats.

Immediately, Captain Prothero ordered all hands to the boat stations. By flags, he signalled to the other ships of the convoy to send out wireless calls. He then ordered rockets to be fired to attract patrol vessels in the vicinity. After that, the other ships scattered and went on at full speed to escape the still lurking submarine.

As the ship started to settle at the head with a slight list to port, the passengers and crew left the ship. In all, eleven boats were lowered. Captain Prothero, the chief officer, first and second officers and the gunners remained on the sinking ship, seeing to it that all the confidential books and documents were thrown overboard. The captain then signalled one of the lifeboats to come alongside, and he and the remaining crew abandoned their ship. The Carpathia was now sinking more rapidly. An hour later, the submarine was seen surfacing and a third torpedo was fired at the already dying Carpathia, this one hitting about No. 5 hatch. Ten minutes later, the Carpathia was gone, some two and a half hours since the initial impact.

About a quarter of an hour later, the submarine was again spotted, this time appearing to head for the remaining lifeboats. But now, the sloop H.M.S. Snowdrop had come to the rescue and fired about ten shots at the lurking enemy. Although none of the shots managed to hit, the submarine was forced to submerge and escape the scene. After circling the area for some time, the Snowdrop picked up the remaining lifeboats at about 1 p.m. On the evening of July 18th, the survivors were safely landed in Liverpool.

In the sinking, all of the 57 passengers were saved, and of the crew of 223, five died in the explosion caused by the second torpedo. Another three were seriously injured and had to be taken to a hospital upon arrival in Liverpool.

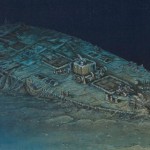

Today, the Carpathia remains were she once sank, at position 49. 28 N., 19. 46 W., about 120 miles west of Fastnet. For a long time, no exploration of the wreck was made. However, on September 9th 1999, the National Underwater Marine Agency, also known as NUMA, announced that they had discovered the wreck of the brave Cunarder. She lies in waters 514 feet deep, sitting upright and in a very good condition. Virtually intact, the only visible damage are the holes caused by the three torpedoes, and it is from these that the only debris come from. It is worth noting that the chairman of NUMA is Dr. Clive Cussler, the man who wrote the fiction novel ‘Raise the Titanic’. His intentions are to return to the Carpathia’s resting place and conduct an extensive exploration of the wreck, perhaps even document it on film.

Specifications

- 558 feet (170 m) long

- 64 feet (19.5 m) wide

- 13,555 gross tons

- Steam quadruple-expansion engines turning two three-bladed propellers

- 13.5 knot service speed

- Passenger capacity of 1,720 people