1905 – 1932

When Germany broke the speed record across the North Atlantic with the Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse in 1897, Great Britain found themselves left behind. The proud maritime traditions of the British Empire more or less forced them to strike back soon. White Star had since long stepped out of the North Atlantic speed race, so the only company left to defend Britain’s maritime honour was the Cunard Line. But they did not have the money to compete. However, Cunard’s chairman Lord Inverclyde soon found a solution. He secured a low-interest loan of £2,600,000 from the British government to aid in the construction of two new superliners – the future Lusitania and Mauretania.

The government posited two conditions, though. First of all, these two new ships would have to be fast enough to win back the Blue Riband from the Germans. Second, they would be constructed in a way so that they in the event of war could be converted into armed merchant cruisers.

When the plans for these new liners began to form, it became clear that they were to become both the largest and the fastest ships in the world. But it was not yet clear how they would be able to reach the 24.5-knot average speed required. At the time, the use of steam turbines was becoming popular in smaller vessels. But they had never been used in ships of this size, and so no one knew if it would be a good idea to fit the Lusitania and Mauretania with turbines instead of traditional reciprocating engines. Cunard soon came up with a way to answer this tough question. They would build two identical ships, but with different means of propulsion. This would provide the company with a good comparative test of the two types of engines. To make everything as equal as possible, the two ships would be built by the same shipyard – John Brown & Co. Ltd.

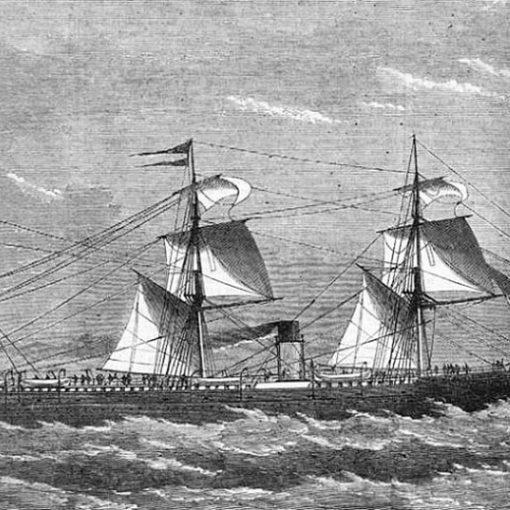

The first of the two ships, the Caronia, was fitted with the traditional type of reciprocating engines. She was launched on July 13th, 1904 and set out on her maiden voyage on February 25th 1905, four days after her sister – Carmania – had been launched. February 21st, 1905, was a day of great public interest. The Carmania was reported to be the forerunner of a new class of giant liners designed to retrieve the Blue Riband, and many had gathered to witness her launch. After having been fitted out, the Carmania was ready for her sea trials. At this early stage of her life she gave clear evidence of the reliability of steam turbines by exceeding her sister’s top speed by over two knots.

The two sisters Caronia and Carmania represented a new stage in ship design in the Cunard Fleet. Earlier, the funnels had been divided into five equal parts where one fifth was painted black and the other four in Cunard’s familiar orange-red colour. But on the Caronia and Carmania the ship’s proportions had changed and so the funnels were instead divided into four parts, with the top quarter painted black.

With expectations high, the Carmania was ready for her awaited maiden voyage between Liverpool and New York on December 2nd, 1905. Several engineers were on board the new ship to supervise the performance of her turbines during the crossing. Upon the Carmania’s arrival in New York a few days later, they were all pleased to report that the engines had worked splendidly. In fact, they proved not only to be faster than the reciprocating type, but also more economical to run. The question of the Lusitania’s and Mauretania’s engines had once and for all been answered – they would both be powered by turbines.

Through the following years, Caronia and Carmania maintained Cunard’s Liverpool-New York service and were joined by the new Lusitania and Mauretania in 1907. As expected, their turbines gave them the speed to beat the Germans. In 1910, the Carmania got her first taste of bad luck when a fire broke out on board the ship while at its dock in Liverpool. The fire brigade was soon on the job, but it took them some time to fight the blaze. When finally extinguished, the fire had caused great damage. Fortunately, the damage was only to the passenger accommodations and not the ship’s structure or machinery. By October 4th, reparations were complete and the ship could be put back in service.

Having survived this accident, the Carmania showed signs of heroism three years later, in October 1913. While en route from New York to Liverpool, the Carmania intercepted an SOS call from the emigrant ship Volturno. The Volturno, which was on its way from Rotterdam to America with emigrants, was on fire caused by the ship’s cargo of barium oxide. Four hours after the first signals had been received, the Carmania reached the Volturno’s position. Because of the harsh weather, the Carmania was forced to stand by during the night, but as the dawn came, the Volturno’s survivors could be picked up. 103 passengers and 30 crewmembers of the Volturno were lost. Awards of gallantry were subsequently presented to the Carmania’s commanding officer Captain Barr and the rest of her crew.

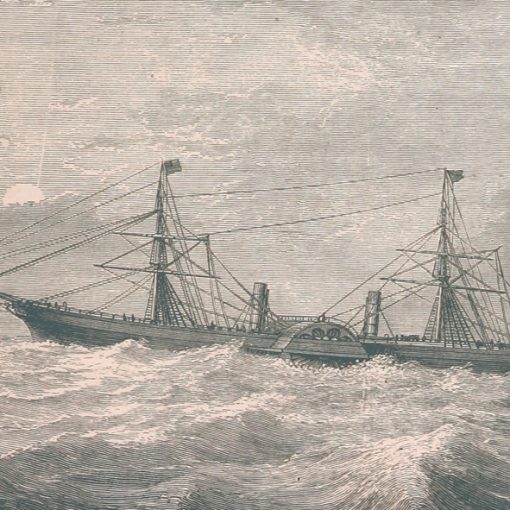

In August the following year, World War I broke out. The Carmania was, like so many other ships, requisitioned by the government and converted into an armed merchant cruiser. This use of the great liners was soon to be proven unsuitable, but the Carmania was one of the few ships that made good use in this guise. In September of 1914, under the command of Royal Navy Captain Noel Grant, the Carmania intercepted the Hamburg-Amerika liner Cap Trafalgar, also converted and armed, in the waters off Trinidad. A fierce battle took place and although the Carmania’s bridge caught fire, she managed to keep firing at the Cap Trafalgar. After an hour of fighting, the Cap Trafalgar took on a list and then went down at the head. The Carmania had received a total of 79 hits, and seven crew members were lost in the battle. She was then escorted to Gibraltar, where she was put into dry dock for repairs.

The Carmania was ready for service again on November 23rd. The ship patrolled the coast of Portugal and the Atlantic Islands until May of 1915, when she was called in to assist in the Gallipoli campaign in the Mediterranean. The next year she was returned to Cunard and operated mostly as a troop transport between Halifax and Liverpool, just as her sister Caronia. When the Great War finally came to an end, the Carmania and Caronia were kept on to return Canadian soldiers to their home country.

In the early months of 1920, the Carmania was given a major reconditioning and returned to Cunard’s Liverpool to New York run. In 1923 she again had a refit during which her passenger accommodations were reduced to 1,440 people, mainly to make her suitable as a winter-month cruise ship. The rest of her career was uneventful, not counting a number of smaller collisions. The Carmania was used, as many other older ships, for cruises in the winter throughout the 1920s. But the Great Crash of 1929 made times worse for the shipping companies. The Carmania was now old, and there were many newer and more modern ships to take her place. And so, in March 1932, she was sold to the shipbreaking firm of Hughes Bocklow & Co. She was subsequently scrapped at Blyth.

Specifications

- 675 feet (206.2 m) long

- 72 feet (22 m) wide

- 19,524 gross tons

- Steam turbines turning three propellers

- 18 knot service speed

- Passenger capacity of 2,650 people as originally built, reduced to 1,440 people in 1923