1938 – 1945

Germany was one of the countries that suffered worst from The Great Crash of 1929. Along with many European nations, Germany was cast into the darkest of economic times. As a result, the number of unemployed people increased greatly. This situation paved the way for Adolf Hitler and his National Socialist party, and they came to power with the election of 1933. The Nazis’ primary objective was to bring Germany to the position of being the greatest nation of the globe, no matter the cost. Violating the Versailles Treaty of 1919, they soon began rebuilding the country’s military forces, thus creating a great number of job opportunities for the people.

The country’s pride on the high seas also needed to be reinforced. The two German superliners of the early 1930s, the Bremen and Europa, no longer held the Blue Riband. Yet Germany would not go for this prize, they would instead start a special type of cruising activity. The highly effective propaganda makers in the Third Reich conceived the idea that would soon be known as ‘Kraft durch Freude’, or ‘Strength through Joy’, in 1934. Commonly known as the KdF, the program was partly a result of the Depression.

When the Nazis came to power, they soon sequestered all trade unions in Germany. All workers were instead to join the Deutsche Arbeitsfront (DAF) or German Labour Front. Naturally, not all workers would do this if they could gain nothing from it, so Hitler needed a carrot to lure them with. The answer lay in the Kraft durch Freude-scheme. As a member of the DAF, a worker would be given the opportunity to go on low-price ship cruises to exotic destinations. This would make the workers happy, thereby increasing their work ability – hence the expression ‘Strength through Joy’. The offer of cruising was also given to the members of the Nazi party.

When the program first set off, the ships needed were taken from Germany’s three largest shipping companies; the Hamburg-Amerika Line, Norddeustcher Lloyd and the Hamburg South-America Line, in Germany commonly known as Hamburg Süd. Ships as the Dresden, Der Deutsche, Oceana and Monte Olivia which might otherwise have been laid up during the Depression were now put to good use. The KdF-program soon proved to be one of the Nazis’ greatest ideas. The Germans loved the cheap cruises, as they gave them the opportunity to visit places they had never thought possible. During the first three years of the KdF-program, the ships were nearly booked solid on every voyage. This led the DAF to order two especially built cruise ships for the program.

One of these ships was built as yard no. 511 at the shipyards of Blohm & Voss in Hamburg. It had been decided to have the name of a high-ranking Swiss Nazi who had been assassinated in 1936 – Wilhelm Gustloff. On May 5th 1937, the new ship was launched in the presence of among others Adolf Hitler himself. The late Wilhelm Gustloff’s widow gave the ship her husband’s name, and sent it to the water by smashing a bottle against the ship’s bow.

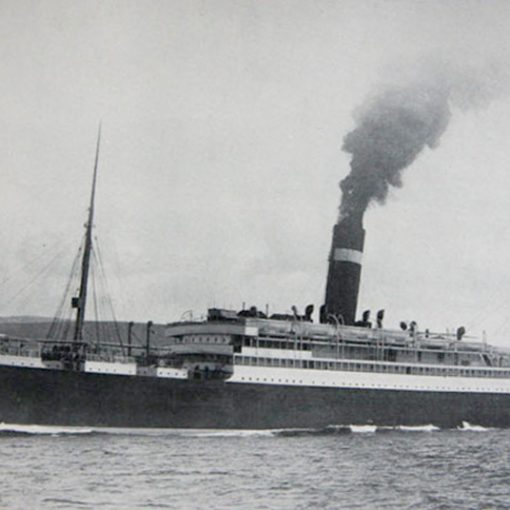

The Wilhelm Gustloff and her running mate Robert Ley, which was being built at the yards of Howaldt in Hamburg and would enter service in 1939, would go into history as the world’s first purpose-built cruise ships. These two vessels brought equality to the high seas. All cabins on board lay along the side of the ship’s hull, so that no one would lack a supply of natural illumination. The passengers were not divided into classes, and it was notable that the crewmembers were given the exact accommodation as the passengers. The ships had not been built as luxury ships, but simply as comfortable ones. Therefore, there were not more passenger amenities than needed. Nevertheless, the German people loved them and the cruises they offered.

As the two ships had been built with leisure cruising in mind, their engines would not be able to bring them above the speed of 15.5 knots. With a deep draught of only 21 feet or 6.5 meters, they would be able to visit also smaller ports on their voyages.

The Wilhelm Gustloff set out on her maiden voyage on April 2nd 1938, on a North Sea KdF-cruise. Although owned by the Deutsche Arbeitsfront, the ship was managed by the more experienced Hamburg Süd. These cruising duties continued for a year, with the ship cruising in the Mediterranean and Atlantic Ocean as well. But then another task was given to her. In May 1939, the Wilhelm Gustloff, Robert Ley, Der Deutsche, Stuttgart, Sierra Cordoba and the Oceana were used for bringing home the so-called Legion Condor from Spain, where it had helped Franco’s Nationalists defeat the Spanish republican forces.

Then on September 1st 1939, Hitler marched into Poland and set off what was to become the Second World War. Naturally, no cruising could be done in the time of war, so the Wilhelm Gustloff was instead commissioned by the Kriegsmarine as a hospital ship on September 22nd. Her first mission in this role was to take on wounded from the defeated Polish army. Between the months of April and June in 1940, the Wilhelm Gustloff operated in Norwegian waters, taking on wounded from the Norwegian invasion campaign. On June 18th, she left Oslo with wounded soldiers on board and sailed for Germany. This was to be her last task as a hospital ship.

In November of 1940, the Wilhelm Gustloff was sent to the German port of Gotenhafen, where she would serve the Third Reich as an accommodation ship. There she remained until the last days of the war in 1945. By then the Germans luck had changed and their forces was now on the retreat. It was then decided to give the Wilhelm Gustloff a new mission.

On the eastern front of the German Reich, Soviet forces were now marching swiftly towards Berlin. This resulted in millions of soldiers, refugees, sick and wounded that had to be evacuated quickly. For this purpose the Germans called upon the services of nearly all the former KdF-vessels, as well as using a large number of freighters to transport people. The Wilhelm Gustloff was to play a part in one of the greatest naval evacuations in history.

On the freezing and blustery morning of January 30th 1945, the Wilhelm Gustloff steamed out of the harbour of Gotenhafen. Cramped with more than 6,000 people, the Gustloff now set out unescorted across the Baltic Sea. The only protection against enemies was the few anti-aircraft guns carried on deck, nothing more. The evacuation was truly a desperate feat. But later that night, a few minutes after 9 p.m., the escaping Wilhelm Gustloff was spotted by the Soviet submarine S-13. The Russian commander did not hesitate and immediately fired three torpedoes on the Gustloff. The first torpedo hit on the starboard side, just below the bridge, followed by the other two further aft, hitting the engine room. The ship quickly took on a list to starboard, and began to settle in the cold, black water of the Baltic. The stern rose into the air as the Wilhelm Gustloff started her journey towards the seabed. Needless to say, the chances of survival for the 6,000 – perhaps 7,000 – men, women and children on board were very small. The water was ice cold, a temperature in which no human can survive for more than a few minutes.

Less than an hour later, the Wilhelm Gustloff was gone and had taken with her at least 5,200 people. About 1,000 people were amazingly saved by the small German vessels T-36, the Löwe, the M341, the TS2, the TF19 and the V1703 who had all been in the vicinity. Yet the terrible loss of more than 5,000 people was horrible and still ranks as one of the worst sea disasters in all history. Looking back at the fact that this was the dying days of World War II, it also counts as one of the most unnecessary. It can probably only be explained with the very special sentiment against Germans that existed at the time, but it is still no good explanation.

Today, the Wilhelm Gustloff remains on the bottom of the Baltic Sea. Her bow and stern is rather well preserved but the midsection has collapsed upon itself. The site has been marked as a gravesite and any visits from divers are prohibited.

Specifications

- 684 feet (208.9 m) long

- 77 feet (23.5 m) wide

- 25,484 gross tons

- MAN diesels turning two propellers

- 15 knot service speed

- Passenger capacity of 1,465 people