1888 – 1923

Also known as New York

In the 1880s, the quest for size and speed was raging on the North Atlantic. Owning and operating the largest, fastest or most luxurious guaranteed a shipping company a whole lot of free publicity, something that was vital in the fierce competition from other lines. Newspapers enthusiastically reported the comings and goings of the great liners of the world, and the public loved to read about the mind-boggling facts and specifications about them.

The Liverpool & Philadelphia Steam Ship Company, which had been founded in 1850, was by now more known as the Inman Line, and it too wanted its share in the action. However, financial and maritime troubles had scarred the company, and they could simply not muster the necessary funds for the new ships needed to match their rivals. The company was forced into voluntary liquidation in 1886, when it could no longer find money for unpaid debts. It seemed as if the Inman Line was to become history soon.

Yet rescue soon came, from an American financier by the name of Clement Acton Griscom. His consortium, the International Navigation Company, already had the Belgian company Red Star Line and the American Line under its wings, and following some negotiation, the Inman Line was purchased and became the third separate subsidiary of the INC. With this, the company was renamed the Inman & International Line. All of a sudden, funds for new tonnage was available through the INC.

So now the company could approach the shipyards of J. & G. Thomson, Glasgow, and place an order for two new vessels. Not just any vessels, these two were intended to turn the Inman & International into one of the finest shipping companies operating on the North Atlantic. The blueprints called for the largest and fastest liners on the run so far, with a size exceeding the 10,000-ton mark. The two would be near identical sisters, and decorated with great luxury.

The first of the two, labelled yard no. 240, was launched and christened City of New York on March 15th, 1888. Her sister, the City of Paris, would follow some seven months later. A little less than five months later, on August 1st, the City of New York was ready to set out on her maiden voyage from Liverpool to New York. With this event, the Inman & International Line could boast with operating one of the absolute greatest ships on the North Atlantic run. The luxury on board the City of New York was unprecedented; passengers could enjoy such amenities as electric lighting, electric ventilation and not to mention hot and cold running water. The public rooms were the finest of its time, boasting such splendid areas as the walnut-panelled First Class smoking room or the library, complete with stained glass windows and 800 volumes. The City of New York also offered 14 private suites for the really well-to-do, including a bedroom and sitting room done in Victorian style.

The ceiling in the First Class dining saloon was adorned by a great glass dome, which provided generous natural illumination. Throughout the ship’s career, this dome would crash in under the rigors of the North Atlantic on numerous occasions. There were in fact quite a few times that stewards had to seal off the soaked areas, and the destroyed carpets and furniture had to be replaced when the ship reached shore.

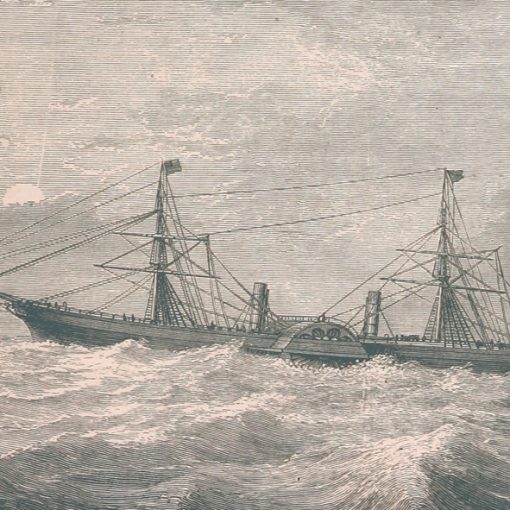

But not only revolutionary on the inside, the City of New York and her sister were indeed something special on the outside as well. What almost seemed as a throwback to the earlier days of sail, they had clipper-like bows, complete with bowsprit. The three raked funnels amidships were accompanied by three masts, ready to set sail should it ever be necessary. This was a time of great evolution of the steamers, and the two Inman sisters introduced a feature that would once and for all make sails a thing of the past – twin screws. On earlier liners, the engines had been geared to a single propeller. Propeller shafts snapping in mid-ocean was not uncommon, and when that happened, ships had to rely on sails to bring them to their final destination. With two propellers, the chance of both shafts breaking down was almost nil, and sails would never be used to any extent on either of these two ships. Actually, the very first ship with twin screws on the North Atlantic was the French Washington from 1864. Originally a paddle steamer, this ship was rebuilt with two propellers in 1868. However, the City of New York and her younger sister were the first ships originally built with this propulsion arrangement.

The maiden voyage of the City of New York was a success, although she had not been able to capture the Blue Riband from the current record-holder, Cunard Line’s Etruria. Time would show that the City of Paris was the faster of the two ships, holding the Blue Riband for both east- and westbound crossings at one point. However, the City of New York had her share of the glory when in 1892 she set a new eastbound record with an average speed of 20.11 knots. Although she lost the prize to Cunard’s speed queen Campania the following year, she had proven her worth and lived up to the expectations of her owners.

That same year, in 1892, the British government withdrew is subsidies from the two Inman steamers. This meant financial worries for the company, and Griscom came up with the solution of transferring the two ships within the INC, to the American Line. Yet there was a catch – a US law that required American-flagged vessels to be built in the country. Griscom was able to win the grant of exception from congress, by promise to commission two new liners from American shipyards. These two ships were to be the St. Louis and the St. Paul. It was also agreed that the ships were to be available for possible war duties.

And so, on February 22nd 1893, the City of New York was transferred to the American Line and registered under the American flag. With this event, the trademark Inman-prefix ‘City of’ was removed, and the ship was renamed simply New York. With a slightly decreased passenger capacity, the New York was placed on the company’s New York-Southampton route. She remained in this service for the following five years. Then, her commercial career was interrupted by war. In 1898, the US government appropriated the New York for use as an auxiliary cruiser. She was sent to the Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry Docks Company to receive her batteries and be converted for navy use. The vessel was renamed USS Harvard, and was commissioned on April 26th, 1898 at New York, and placed under the command of Captain C. S. Cotton. The vessel was then sent to the West Indies assigned as a scout, to help locate the Spanish fleet. On June 7th 1898, the Harvard went back to Newport News. She remained there until June 26th, when she was given new duties of carrying troops and supplies to Cuba.

Following the naval battle of Santiago, the Harvard was ordered to aid in the rescue of Spanish sailors from the burning wrecks of the Almirante Oqunedo and the Maria Teresa. Dropping nine of the ship’s boats and sending them into the turmoil of firing and exploding ammunition, the crew of the Harvard was able to rescue 35 officers and 637 men from the wrecks. Many of the saved Spanish sailors had lost everything in the horrible carnage of the fires on board their ships, and they were given new clothing, hats and shoes upon their arrival on board the Harvard. The most seriously injured were transferred to the hospital ship Solace, while the others were incarcerated on the Harvard as prisoners of war. But this heroic effort was soon to be overshadowed by a tragic event that would be known as ‘The Harvard Incident’.

On July 4th 1898, the Harvard lay at anchor off Siboney, Cuba. The prisoners of war were being guarded by members of the 4th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry. A line had been marked on the ship’s deck, beyond which the prisoners were not allowed to pass. Near midnight, a prisoner appeared to make an attempt to cross the line. No one knew why, it was later suggested that he might have been trying to avoid the heat. He was ordered to return, but failed to do so, possibly because he did not speak English. The sentry fired, causing the other prisoners to rise to their feet. Thinking that the Spanish prisoners were about to attack, the men of the 4th Massachusetts fired a volley into the mass of prisoners. When the smoke had lifted and order had been restored, six Spaniards lay dead and thirteen more were injured. The incident was found to have occurred through ‘a sad mistake’.

Following this tragic event, the Harvard was used for transporting American troops back to the US. On her final war voyage, she left Santiago on August 21st and arrived at Montauk Point on August 25th, 1898. She was then decommissioned on September 2nd, and returned to her owners and given back the name New York. In January the next year she resumed her regular New York-Southampton service. However, after only three days of her first post-war crossing, the New York’s starboard engine broke down. The ship was brought to Southampton, were the she went through repairs. Three months later, she was ready to resume service. In April that same year, she was again taken out of service, this time in order to go through a rather extensive refit. The ship’s original triple-expansion engines were replace by new ones, and her three funnels were replaced with two taller ones. On April 14th 1903, the New York was back on the Atlantic, as usual on the New York-Southampton trade. She remained in that service for the following decade.

What was to be the New York’s perhaps most famous incident occurred on April 10th 1912, when she nearly collided with the Titanic on her maiden departure. While the brand-new White Star liner was moving down the River Test to reach open waters, she passed the New York which was moored on the outside of the Oceanic. As the Titanic passed the two ships, hydrodynamic forces pulled the New York from her moorings and she was drawn towards the Titanic. Yet swift action taken by the Titanic’s bridge crew and tugboats in the vicinity managed to keep the two ships from colliding. The collision and the subsequent delay it would have caused to the Titanic’s maiden voyage was avoided. It is easy to suspect that history might have looked a lot different if the collision had not been prevented from happening.

In 1913, the New York was evidently an old ship, and newer vessels had made her very old-fashioned and outdated. With this in mind, the American Line decided to remove the ship’s First Class fittings and make her a Second- & Third Class-ship only. In 1914, she was transferred to the New York-Liverpool run. That same year, the First World War broke out. The major liners of the world, such as the Olympic, Aquitania, Mauretania, Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse and Kronprinz Wilhelm were called in for war duties. But the now ageing New York was not required for immediate military service, and she remained on her commercial run through nearly the whole conflict. But in 1918, she was again taken by the US Navy and commissioned as the USS Plattsburg. In this guise, she made eleven cruises to Europe carrying troops to war zone as part of the final offensive against Imperial Germany, and then bringing them home. She was returned to the American Line on October 6th, 1919.

The ship was given back her name New York, had one of her three masts removed, and resumed transatlantic service in 1920. Being a very old ship, she stayed with the American Line only for another nine months. In 1921, the New York was sold to the Polish Navigation Co. who retained her name and used her for one round voyage New York-Antwerp-Danzig-Southampton-Cherbourg-Brest-New York. Her new company was in serious financial difficulties and the ship was then seized for debt and sold. In 1922 she went to the Irish American Line and later the same year to the United Transatlantic Line. On June 10th1922, she left New York for the last time for the American Black Sea Line on a voyage to Naples and Constantinople where she was sold for demolition at auction by order of the US government. The New York spent her last days in Genoa, where she was scrapped in 1923.

Specifications

- 560 feet (171.1 m) long

- 63 feet (19.3 m) wide

- 10,508 gross tons

- Steam triple expansion engines turning two propellers

- 20 knot service speed

- Passenger capacity of 1,290 people