1957 – 2004

Also known as Rhapsody and Regent Star

The end of the Second World War in 1945 saw a Europe in devastation. Virtually entire nations lay in ruins after countless bombing raids, and the difficult task of rebuilding would take some time. Yet with the aid of the Marshall Plan, the European nations slowly began to recuperate.

The shipping lines, which on both sides had all lost numerous vessels in the bloody conflict, played a substantial role in reviving the financial situation. The trade routes had to start moving again, and for this purpose new ships were needed, both for cargo and for passengers. But the new ships emerging from the shipyards would not be like their pre-war counterparts. When the dust from the war had settled, the Armistice had heralded the dawning of a new era. The world was no longer the same, and neither were the old class distinctions. Eventually, this was reflected in the design of ocean liners as well.

Although being one of the European nations that had suffered the most damage during the war, the Netherlands quickly made a remarkable comeback on the shipping scene. The national pride on the North Atlantic – the Nederlandsch-Americaansche Stoomvart-Maatschappij, NASM for short but commonly known as the Holland America Line (HAL) – definitely signalled their resurrection when the company flagship Nieuw Amsterdam returned to service in October 1947. And there was still more to follow.

Recognising the huge demand for Tourist Class berths on the North Atlantic run as the 1950s drew closer, HAL decided to make an innovative move. Two intended cargo liners were redesigned as passenger liners, and eventually entered service as the Ryndam and Maasdam in 1951 and 1952 respectively. Marketed as ‘The Economy Twins’, these two liners quickly became very successful. Ryndam and Maasdam were both on the smaller and slower side of the scale, but this only made them far more economical to operate than the ‘conventional’ liners at the time. But the really revolutionary aspect of this pair was the fact that they were devoted almost completely to Tourist Class travellers. By offering transatlantic crossings at very affordable prices, the Economy Twins became very profitable.

In light of the success of Ryndam and Maasdam, Holland America Line soon decided to continue on the same line, although this time with a larger ship. The initial designs were started on in 1954 and this time, since the ship would be designed from the start as a passenger liner, a number of improvements could be incorporated into the design. She would be nearly 10,000 gross tons larger than the Ryndam and Maasdam, and this extra size would allow for a better sea-keeping hull shape. Fitted with two screws, her service speed would be higher than that of the Economy Twins, and Tourist Class would once again be pre-eminent although of a higher standard.

With the basic outlines decided upon, HAL now signed a building contract with the Schiedam yards of N.V. Wilton-Fijenoord. When the blueprints had been completed and approved, the actual construction process could commence. However, the new ship was not to be built on a slipway, which was the usual way of doing things at the time. Instead, just like the United States a few years earlier, she was constructed within a dry dock, which would eventually lead to a – for the time – unconventional birth for a liner. This odd choice of technique actually led to much local publicity and speculation, but with hindsight it can be said that HAL was merely a bit ahead of their times. Today, dry dock construction is the common way of building ships.

As time passed, the new vessel started to take shape in her dry dock. Then, on June 12th 1956, they day of launch had arrived. Or perhaps ‘launch’ is not actually the appropriate term here. Since she had been built in a dry dock, the new ship was simply floated out. Perhaps not as symbolic or majestic a method compared to a slipway launch, but definitely a safer one, the new ship was born with significantly less pomp and splendour than ordinary. In fact, there was not even a naming ceremony held for the occasion. Holland America had decided to announce the ship’s name at a later stage, and so she was moved to her fitting-out berth unchristened.

On November 17th 1956, Captain Cornelis Haagmans arrived at Schiedam to supervise the final stages of construction. As the ship’s future first master, it was customary for him to get familiar with his command as soon as possible. His duties also included taking the ship out on her various trial runs, the first of which was on December 15th 1956. This was an engine trial, but things did not start very well as the ship encountered a very bad storm that same night. On the following morning, the ship’s engines broke down and she had to be towed back to Schiedam by five tugboats on the 17th. The disappointment among the 264 shipyard and HAL employees on board must have been tremendous, indeed.

Back at the yard, the engine problems were dealt with. However, these mechanical flaws would periodically surface again during her career. In particular, the ship’s boilers would cause some worries, since they were of an untried, experimental type. Nevertheless, after a month’s time the ship was ready for her next run, the technical trial. With 476 people on board, she left Schiedam at 9 a.m. on January 14th1957. This time, she would fare much better. Whilst at sea, the crew tried out her top speed (which amounted to 21.9 knots), the smallest circle to turn her around, how long it took to heave the anchors home again etc. After having performed perfectly satisfactory, the ship headed back to her builders, where she arrived early in the morning of January 17th.

Two days later, on January 19th, the new ship left her builder’s yard and sailed for her home port of Rotterdam. She arrived there after a short, two-hour trip, and was then prepared for her official sea trial and delivery voyage. On January 23rd, she left her berth and headed out on the North Sea with some 500 guests on board, including the 18-year old Dutch Crown Princess Beatrix who was present for a very special reason. The time had finally come for the ship to receive a name, and the Crown Princess had been chosen to do the honours. During a special ceremony in the ship’s restaurant, Princess Beatrix poured a glass of champagne over the ship’s 300lb bell and gave her the name Statendam. At last, the new ship had an identity of her own. As the fourth ship in Holland America Line’s history to bear that name, she would carry on a splendid line of heritage.

Statendam arrived back in Rotterdam the following morning, and preparations were made for her maiden voyage, which wasn’t far off by now. On February 6th 1957, she slipped her moorings and set out under Captain Haagmans’ command. With New York as final destination, the ship would call at Le Havre and Southampton on the way. During that time, the 877 passengers and 474 crewmembers on board started to get to know the new vessel.

Outwardly, the ship sported perfect proportions. With a superb bow section, a rounded stern, sleek lines in between and a beautifully shaped funnel to top things off, she was soon rightfully considered one of the most stylish liners of the day. Needless to say, the lovely classic Holland America Line dove grey hull and buff funnel with the company colours emblazoned upon it certainly didn’t make her any less smart-looking.

Internally, the new Statendam could hardly disappoint. As with the Economy Twins Ryndam and Maasdam a few years before her, nearly the whole ship was designed almost exclusively for Tourist Class passengers. She had accommodations for 867 Tourist Class travellers, and although there were also berths for 84 people in First Class, these were there mostly to comply with the two-class requirements of the trans-Atlantic Passenger Steamship Conference.

In this respect she was very much alike her smaller fleet mates Maasdam and Ryndam, but the Statendam offered so much more in terms of comfort and convenience. Her improved design included private facilities in 90% of the Tourist Class cabins, and added to that her larger staterooms, open-air pool and larger outdoor deck spaces made her easier to adapt and more suitable for cruising in the off-season. But she also had features specially intended for the North Atlantic, such as enclosed promenade areas.

Statendam’s interior spaces were of a more contemporary décor than those on board previous HAL ships, but they were well praised nonetheless. Continuing a Holland America Line tradition, the ship boasted exotic woods such as bleached ash, bubinga and Rio rosewood. The Tourist Class Main Lounge featured a floor area of 5,380 square feet, and was done in warm colours such as yellow and old rose. There was a parquet dance floor, and the indirect lighting provided a cosy atmosphere. Capable of seating 460 people – that is more than half of her total Tourist Class capacity – the lounge was also adorned by multi-coloured ceramic depictions of the four seasons. Holland America had also included a Palm Court and Verandah on the Statendam, just as they had done on many other previous liners. The secluded First Class Verandah was done in a bright and cheerful fashion, with walls panelled in cherry and a multi-coloured linoleum relief of the five continents. From here, glass doors led to the Lido Deck and outdoor pool. Other areas included the Anteroom, located just forward of the Smoking Room. Decorated by a tapestry entitled ‘By the Well’, this room was done in more cool colours, with chairs in pale blue upholstery and a light beige carpet. The Ocean Bar, on the other hand, made use of black and grey for its floor and ceiling, while accentuated by the lemon yellow, pale red, grey and black on the tables, chairs and stools. And with the nature of the room in mind, the designers had incorporated humorous line drawings on the walls and tabletops.

However, in spite of the stylish and enjoyable interiors, the Statendam’s premiere voyage was not an all-out pleasurable one. During the crossing, the ship encountered heavy seas, which led to many cases of Mal de Mer among the people on board. To get out on deck for a bit of fresh air was much too dangerous, but the crew made their best to make the crossing as nice as possible by maintaining the entertainment for those still up and about. Those passengers brave enough to venture a round on the dance floor soon discovered the difficulties of dancing on a liner pitching, heaving and rolling in the heavy seas and eventually a security rope had to be put up around the dance floor to prevent serious injuries.

When the ship finally arrived in New York, she was not greeted with as festive a gala that is customary for a new liner. The reason for this was a strike among the harbour tugs, and this not only meant that her greeting escort was smaller than expected, it also meant that the Statendam would have to dock without tugboat or dock pilot assistance. Fortunately, Captain Haagmans was lucky to arrive off the company’s Hoboken pier at slack water, but not having enough practice with the ship and how she would behave, Captain Haagmans admitted that the docking was no easy task: ‘I first brought a headline ashore with our own lifeboat and dropped one of my anchors, then I heaved her slowly alongside; not too slow to beat the incoming tide. At 7:10 a.m. it was all over and we were docked without any mishap.’

Following this eventful maiden voyage, the Statendam remained in New York for a few days before sailing on three cruises to the West Indies. Holland America had already realised that new ships had to be built for the dual purpose of transatlantic crossings and cruises, and the new Statendam was no exception. On these cruises, she sailed as a one-class vessel, with a slightly smaller passenger capacity to give the vacationers a little more room on board. Averaging some 650 passengers on each of these cruises, the Statendam was ready to cross the North Atlantic again on April 16th.

Between May and December of 1957, Statendam then made another ten North Atlantic voyages, carrying almost a full complement of passenger on every occasion. Following two cruises to the Caribbean, it was then time to summarise the ship’s first year in service. Holland America could probably not have been more pleased, since the Statendam had proved even more popular than the Ryndam and Maasdam. The ship had now settled into her regular service, but another celebrated voyage was about to take place.

On January 7th 1958, the Statendam left New York and set out on a 110-day circumference of the globe, on Holland America Line’s first ever world cruise. For the occasion, the ship had been fitted with two extra motorboats on top of hatch no. 2. Presumably, this was to make shore excursions easier. With a regular crew of 503 people and an additional cruise staff of 26, the passenger compliment amounted to only 351 people. Although this might appear as a somewhat low number, it probably reflected more the exclusiveness of this particular voyage. This crew/passenger ratio of almost 2 to 1 would only guarantee a very high degree of service.

Statendam’s first port of call on this world cruise was the Cape Verde Islands, but the encounter of a violent east-south-easterly gale resulted in a somewhat dubious beginning of the voyage. One of the extra motorboats was lost in the heavy winds, and the subsequent delay forced the ship to cancel the first port of call. Instead, she headed towards Dakar, where she arrived on January 14th. From there she continued to Freetown and Pointe Noire, where an amusing but serious incident would occur when the ship was leaving port.

When the harbour pilot came on board to take the ship out, Captain Haagmans advised him that the Statendam had very good reverse power. Taking no heed of this warning, the pilot ordered the engines to ‘slow astern’ instead of the recommended ‘dead slow’. As Statendam was docked very close between two other ships, this reckless manoeuvre could have ended in disaster. But through a miraculous stroke of luck, everything went well, albeit at a very small margin. Statendam’s lines snapped, but she did not run into the ship lying astern of her. Instead, Statendam continued backwards and passed the other ship along her whole length at a distance of not more than four feet. The pilot then let Captain Haagmans handle the engine orders, and could safely bring the ship out of the port. With this dramatic event behind her, the Statendam could continue her world cruise.

Via Luanda, Walvis Bay, Cape Town, Durban, Zanzibar and Mombasa, the ship arrived at Bombay where she remained for a full week to allow passengers to make a trip to Nepal. Following this pause, Statendam continued via Ceylon, Penang and Singapore to Bangkok. However, the ship herself was not able to sail up the river to visit the city, because her draught was too deep. Instead, she anchored off the estuary where a coastal vessel came alongside and took on passengers for transportation up the river.

As the rest of the cruise continued, the Statendam sailed to Bali, Manila, Hong Kong, Formosa, Okinawa and Yokohama before proceeding to Honolulu, San Francisco and Acapulco. From there, she passed through the Panama Canal and called at Cristobal before returning back to New York again. She arrived there on April 26th, thus concluding Holland America Line’s premiere world cruise as a splendid success. Three days later, she returned to the North Atlantic trade when she sailed back to her home port of Rotterdam on April 29th 1958. Following a quick ‘shave and a haircut’ in dry dock there, she returned to service to spend the summer season on the Atlantic Ocean. In June that year, Captain Haagmans was transferred to the company flagship Nieuw Amsterdam for his last voyage as Captain. But upon his retirement at the age of 60 he once again boarded his ‘good Statendam’ – although this time as a passenger – to get back to New York. It must have been a very special and emotional voyage for him, indeed.

And so, under her new commander Captain D. Van Dalen, the Statendam continued her dual service as both a liner and a cruise ship, spending three quarters of each year on the North Atlantic. When she reprised the successful world cruise in 1959, it was not only the second such voyage for her, but also for the Holland America Line. The ship’s shorter cruises to the Caribbean were also very popular, and if anything, these pleasure voyages were telltale signs of what the future had in store for the great ocean liners.

As the 1960s unfolded, the transatlantic shipping scene changed dramatically. More and more passengers now chose to go by air instead of sea, and many ships’ services on the North Atlantic became less needed. As a result, the ocean liners’ duties became more focussed on pleasure rather than dispatch. The Statendam was no exception. Her time on the North Atlantic was reduced every season, and by 1966 she was more or less a full-time cruise ship, although she made the odd transatlantic crossings until the summer of 1968, at least. The two-class system was abandoned, and her load capacity was reduced to 650 passengers.

Holland America Line saw great potential in the Pacific Ocean, and they started operating the Statendam from the American west coast. Out of San Francisco and Los Angeles, she made luxurious cruises to the South Seas, Australia and the Orient, often carrying movie stars and other famous VIPs. The venture proved highly successful, but this glamorous type of voyages required a brand new ship, so the Statendam was replaced by the affiliate company German-Atlantic Line’s new Hamburg after only a few years. Statendam was then sent back to New York, from where she made Caribbean cruises as well as longer voyages to the Mediterranean and North Cape.

However, the changes in the industry were not only evident in the ship’s itineraries, but also in the attitude of her owners. As their offered voyages went from crossings to cruises, Holland America had to evolve accordingly. In February of 1971, HAL purchased one million shares of Westours Inc. at $1.25 each, thus acquiring 85% of the total amount of shares. Westours had been organising tours to Alaska and Yukon since 1947, and this tradition would now be continued by Holland America.

And so, as the company became solely devoted to cruising, it was decided to create a new livery for the fleet to symbolise this historic transition. In September of 1971, the Statendam was taken out of service and sent to her builders for a major refit, during which she was converted into a one-class cruise liner with more accommodation. The enclosed promenade areas disappeared, giving room to new and enlarged lounges and casinos. Her passenger capacity was altered to 740 people, and she was given a lido deck aft. In February of 1972, after five months of work and $7,000,000 spent, she emerged as the first ship in the fleet to sport the new company colours. The grey hull had been repainted in midnight blue, and the funnel colour had been changed to a bright orange. The old green/white/green funnel bands had also disappeared, being replaced with the new logo comprised of three stylistic, cerulean blue/white/cerulean blue waves.

In this modern new guise, the Statendam was soon back in service, mostly making Caribbean cruises out of New York and various Florida ports in tandem with her larger fleet mate Rotterdam. By now her registry had been changed to Curacao, and an Indonesian service staff had joined her. Things were indeed different now. In 1973, the transformation of the company was made complete when it took on the new name Holland America Cruises.

Statendam remained in Caribbean and Bermuda service throughout the 1970s, and in 1979 she was selected together with the Rotterdam to represent Holland America at the New York Harbor Festival. After that she returned to her regular service, and starting in 1981 she also did 7-day Alaskan tours out of Vancouver in the summer. But by now the Statendam was no longer in pristine condition. Her engines, which had always been a source of worry from time to time, were now really showing signs of age. Frequent breakdowns caused disruptions in her schedule and required costly repairs. On a few occasions, she even got into trouble with the local authorities while in various ports, because of her engines producing such foul emissions. In 1982, while off Antigua, her generators failed and resulted in a complete power loss. As lights and air-conditioning went out, the ship drifted for hours before the electricity came back on. The situation was no longer acceptable, and HAL decided to try and get rid of the ship.

So, in October of 1982, the old Statendam was sold to Actus Investment Ltd., to be operated by Paquet Cruises, a French company with Bahamas registry and multinational crews. Following some basic repairs and refurbishing, she was soon back in service with a white hull and the new name Rhapsody. Her itinerary was not much different though, with cruises to Alaska in the summer and Caribbean service in the winter. However, after only a short time in service for her new owners, they started to realise that the ship was not what they had hoped for. Her engines continued to cause problems, and the company was losing money on the whole project.

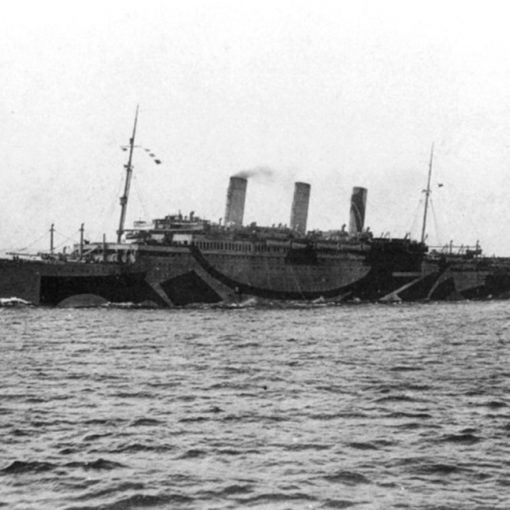

Further worries arose on March 28th 1984, when the Rhapsody ran aground on Grand Cayman, near Georgetown. After having been stuck on the rocks for three days, the displeased and angered passengers were taken off and flown home on the 31st. The Rhapsody was firmly lodged where she lay, and it took more than two months to get her refloated. On June 15th, she finally came off the rocks after much difficulty, and was then towed to Galveston to undergo the necessary repairs. In September she was back in service doing cruises from Port Everglades, but this was merely a last, desperate attempt from her owners to make her profitable again. Her time with Paquet Cruises had been a failure, and she was soon put up for sale again.

On March 11th 1986, the ship was sold for $12,000,000 to the Lelakis Group, headed by the Greek businessman Antonis Lelakis. Renamed Regent Star, she was intended as one of the first ships for Lelakis’ recently founded Regency Cruises. The ship was officially handed over on May 4th at Port Everglades, but was quickly sent to Piraeus, Greece, where she was to go through an extensive refit. 75 extra cabins were installed, increasing her passenger capacity to 950 people. In addition – being very aware of her troublesome engines and boilers – the ship’s new owners had decided to give her a new set of machinery. At Piraeus, the Regent Star’s old engines were replaced with a set of diesels. These were not brand new, though. The engines came from the Margaret Johnson, a container ship which had been bought by Lelakis in February of 1986 to be rebuilt as a cruise ship. When this idea was declared too expensive, her engines were removed and the ship was then sold for scrap.

After having gone through this major refurbishment, the Regent Star entered service for Regency Cruises on July 26th 1987, setting out on a cruise from Montego Bay, Jamaica. From then on, her programme was a familiar one; Vancouver-Alaska cruises in the summer, and sailings in the Caribbean in the winter. In June 1990, however, the ship once again returned to New York for the first Regency voyages from that port. On Memorial Day that same year though, she once again had a taste of misfortune when she went aground some 25 miles up the Delaware River. Luckily, the river ferry Delaware came to the assistance. She manoeuvred alongside the Regent Star’s port side and managed to unload the more than 900 passengers on board. Fortunately, the ship was then able to get off virtually undamaged.

However, Regent Star’s sailings out of New York soon came to an end, as the Regent Sun replaced her on the company’s New York-Eastern Canada service after only a year. She was then sent back to Alaska to resume her old service there. She continued normally until the summer of 1995, when the ship once again became the scene of a dramatic incident. While sailing approximately 65 miles southwest of Valdez, Alaska, a ruptured fuel line resulted in an engine room fire which crippled the ship. Radio calls were sent out and ironically, the first ship to arrive at the scene was her one-time running mate, Holland-America’s Rotterdam, which assisted by unloading the Regent Star’s passengers.

In October of 1995, Regency Cruises folded, whilst their fleet was scattered on their various itineraries. Regent Star was passing through the Panama Canal at the time, on a cruise to the Caribbean, Florida and eventually the Mediterranean. The company had been in financial difficulties for some time, and the crewmembers on board Regent Star were still waiting for their salaries. In addition, the ship was having shortages of food, and when the final announcement about the company’s collapse came, the ship ended her cruise and quickly fled from American creditors to the Mediterranean.

When she arrived in the Med, she was finally anchored in the Greek waters of Eleusis Bay in November 1995. Since then, the ship has remained there, her future becoming more and more uncertain. At one point, she was eyed for possible purchase by a company called CruiseShares who wanted to introduce a timeshare-style system on board a small fleet of cruise ships, but the venture was– not surprisingly – soon abandoned. So, the old Statendam remained in Greek waters, deteriorating slowly, technically under the name Sea Harmony. No one took any interest in her, and eventually she was sold off to Indian shipbreakers. On March 14th 2004, the old Statendam departed Eleusis with the name Harmony I painted on her bow, and the work on dismantling her would soon commence. Perhaps this was the most dignified end to such a long and glorious career, after all.

| Special thanks to Stephen Berry, William O’Donnell, Mike Ridgard, Dominique Vaccaro & Scott Van Valen who so kindly assisted with knowledge and material for this article. |

Specifications

- 642 feet (196.2 m) long

- 81 feet (24.7 m) wide

- 24,294 gross tons

- Parsons geared steam turbines turning two propellers

- 19 knot service speed

- Passenger capacity of 84 people in first class, 867 in tourist class

One thought on “Statendam (IV)”

I was the production manager on the Regent Star, starting in Vancouver 1995, right after her engine fire in Alaska. We crashed into the Panama Canal, went to Florida, then to 4 of 8 ports in the Mediterranean before we were “canceled” at sea. Nobody knew we were bankrupt until we were seized in Sete France for lack of port fees. Then we heard Kawasaki Corp bought the line and we were paid, in the Regency lounge, one table, one strong box full of cash, and one helluva lineup.

We were rescued at sea under distress call, and towed to Piraeus, where we spent a week stranded by the line. Finally, in a fit of rage, a bunch of us walked to the travel agent responsible for our tickets home, and demanded more information. We were on the next planes back to North American airports within 2 hours. Greatest trip of my life.