1927 – 2006

Back in the late 1920s, just before the Depression hit in 1929, the shipping industry was a booming business. The shipping companies had by now recuperated from the devastation of World War I, and great ships were sailing the seas of the world. The busiest sea lane was of course the North Atlantic, where emigrants were still crossing from the Old World to the New. But while most shipping companies were dealing with dispatch, some also offered ocean voyages for the sake of leisure. One of these companies was the Bergenske Dampskipsselskap, or Bergen Line, of Norway. In the mid-1920s, they decided to order a new ship for their tourist trade. Little did they know it at the time, but that ship was to become a legend of the cruising industry.

Many shipbuilders competed for the desirable contract, but in the end the battle was won by the Swedish yards of Götaverken in Göteborg. The contract for the new vessel was signed on August 4th1925, and the builders immediately went ahead to begin the construction. This was the first time that the yard was building a ship for just passenger purposes, and the progress of construction received much attention in the press. But the yard’s inexperience in building passenger vessels also meant that much of the interior design was subcontracted to other firms, such as Selander & Sons who were hired to produce all the expensive woodwork on board.

Work proceeded at a steady pace, and a little more than a year after the contract had been signed, the new ship was ready for her launch. It was Saturday, September 11th 1926, and a great crowd had gathered in the yards as well as on the banks and piers surrounding the area. Miss Lillie Lehmkuhl, the daughter of Bergen Line’s managing director, had been chosen to perform the christening ceremony. When she had wished the vessel good luck on the seas and swung the bottle of champagne with accuracy, she gave the ship its name – Stella Polaris – and sent her down the ways. Entering the water of Göta Älv, a legend was born.

Following the successful launch, the ship was now to be fitted out and completed. As contracted, the Stella Polaris was to have been delivered on April 1st 1927, but as soon as February 20th that year she was ready to go through her sea trials. The event was well covered by the press, and a special group of invited guests were on board for the occasion. Stella Polaris’ trials went as planned, and she was soon ready to enter service for her owners.

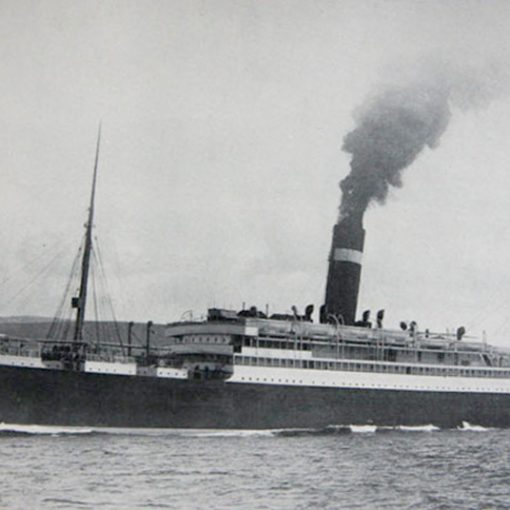

Outwardly, as well as internally, the ship was a full-grown beauty. Her yacht-like appearance was perfected by means of a clipper-bow, complete with a bowsprit and the white hull and light-coloured superstructure was balanced by the two masts and the single, yellow funnel. The ship’s look seemed to epitomise what she was built for – luxurious leisure cruises.

Stella’s interiors were a work of art in its own right. The bridge – which was not enclosed – sported instruments in polished brass and teak flooring. Below the Bridge Deck was the A-deck, where the nine lifeboats were located (two of these were equipped with motors). Further aft were nine passenger cabins, as well as a gymnasium area. B-deck was the location of many public areas. The promenade area for one thing, but here one could also find the Verandah Café, the Smoking Room and the Music Salon. One deck down, on C-deck, was the Grand Dining Room, which could seat 214 guests. A large star, comprising of 150 different coloured lamps, adorned its ceiling. C-deck also housed several passenger cabins, especially noteworthy four deluxe cabins; each designed with its special sort of wood – mahogany, maple, pear and birch respectively. Further aft of these, barbershops, the doctor’s reception and other facilities were sited. D- and E-deck also housed passenger cabins, albeit not as luxurious as the ones previously mentioned. The crew was divided into four-berth cabins, a bit more cramped than the passengers, but nevertheless with nice furnishing and decoration.

Just a week after her successful sea trials, Stella Polaris was ready to set out on her maiden voyage. Saturday, February 26th 1927, was a grey and rainy day in Göteborg. But in spite of this, the mood on board the ship was festive. Scores of visitors were finally requested to go ashore, as the time of departure was approaching. On 12 sharp, Stella Polaris slipped her moorings, and she could finally commence her premiere voyage. Her first port of call was Tilbury, where she was to take on supplies and more passengers. After that, she headed for Lisbon and several Mediterranean ports.

Stella Polaris had soon earned a reputation of being a superb cruise ship, perfectly suited for more intimate voyages. On her regular cruises, the ship carried approximately 200 passengers compared to just half that number on a round-the-world voyage. With a crew compliment of some 130 people, this meant that the passengers received a true first-class service. In the summers, Stella cruised the northern waters of the North Cape, Spitzbergen and the Baltic Sea. During the spring and autumn, the itinerary included warmer ports of call such as the Canary Islands and the Mediterranean, while the winter months were the time of a circumnavigation of the globe.

Stella’s round-the-world voyages were real treats in themselves. Usually, she sailed out of New York in mid- or late January, headed to Cuba and then sailed through the Panama Canal. Once in the Pacific Ocean, Stella Polaris set course for New Guinea, the Philippines, Indonesia and Singapore. From there, she continued via Ceylon and India before rounding the Cape of Good Hope to head north for Freetown, Las Palmas, Casablanca, Tangiers and Gibraltar to finally end the voyage at Harwich.

The magnificent Stella Polaris continued her career like this, and earned quite a loyal following. There were some deviations in her itineraries, though. For instance, one year the company tried to launch two short Caribbean cruises in the winter, before the annual circumference of the world. However, these voyages were not financially successful, so they were soon removed again. And as with so many other ships, Stella Polaris also had her share of misfortune. On the night of June 11th 1937, the Norwegian steamer Nobel failed to navigate properly and came into the path of Stella, resulting in a collision between the two vessels. The Nobel was carrying a cargo of dynamite and ammunition, and the risk of an explosion was imminent. Fortunately, the munitions never ignited and the Nobel sank to the bottom along with her dangerous cargo. Stella Polaris got away with damages to her prow, and a shortened bowsprit. The bowsprit was never again lengthened after the incident, thus becoming sort of a reminding scar of the event.

Stella Polaris continued her services for another two years, until the Second World War erupted on September 1st, 1939. On that day, Stella arrived home in Oslo after a voyage from Stockholm, and she was immediately laid up. She lay idle until April 9th 1940, the day that German troops landed in Norway. To protect their ship, the company then ordered the ship moved to the Osterfjord, close to Bergen. But finally, on October 30th that year, the ship was seized by German forces, which soon put the ship to use as a floating recreation centre for submarine officers. Nearly three years later, on September 1st 1943, Stella Polaris was put under German flag and with a German crew. When the Allied eventually stood victorious over the Axis powers, the ship was handed over to the Ministry of War Transport. In this guise,Stella Polaris was used to transport Russian prisoners of war to Murmansk and for a few trooping voyages between Norway and Leith. Finally, on November 7th 1945, Stella was handed back to her rightful owners – Bergen Line.

But she was no longer the graceful beauty that she once had been. When the ship was taken from the Germans, they had done everything they could to destroy as much of the interiors as they could. Her white hull was covered with rust, and a missing bowsprit made her bow look a bit stumped. But, Bergen Line’s board still saw much use in the ship, and they decided to give her a complete refit. The order was placed at the original builder’s yard – Götaverken.

And so, on the morning of November 14th 1945, the Stella Polaris was heading up Göta Älv towards the place of her birth. Once there, work began to completely renovate the beautiful vessel. There was a lot to be done, but an inspection of the engines showed that they were in very good condition. Apparently, the Germans had had the good sense to employ qualified engineers.

On June 1st 1946, Stella Polaris was delivered back to her owners. Götaverken’s workers had done an outstanding job, and it was virtually a new ship that emerged from the yard. Due to new safety regulations, the passenger capacity had been slightly decreased to 189 people. The bridge had been enclosed and fitted with modern navigational equipment. A completely new Dance Salon had been added, as well as a complete ventilation-system. The extensive refit had been more costly than originally building the ship, and it was now up to Stella Polaris to prove her worth once again.

After a repositioning voyage from Bergen to New York, Stella set out on her first post-war cruise on August 10th. Sailing out of New York, she then headed for the Caribbean archipelago with calls at Nassau, San Juan, St. Thomas, Fort de France, Caraças, Kingston and Cuba, to finally head back to New York again.

During the summer of 1947, Stella Polaris found herself in an unusual role. Bergen Line’s ship on their Bergen-Newcastle run – Venus – was going through a refit, and Stella was called in to fill the gap. In November she crossed the Atlantic to New Orleans, out of where she then made several cruises. In the summer of 1948, she went back to Europe and made a number of voyages between Bergen and London during the 1948 Olympic Games.

Stella Polaris stayed with the Bergen Line into the 1950s, and continued to offer a wide range of different cruises, including a 134-day, round-the-world voyage starting in January 1951. But the company had had the ship on their sale list since the late 1940s, and by now an interested buyer had surfaced. It was the Swedish ship owner Einar Hansen who wanted the Stella Polaris for his Clipper Line. In the spring of 1951, the two parties reached an agreement and in October that year, Stella left Bergen for Göteborg, where she was to go through an extensive modernisation. But first, numerous works of art and other decorations were taken off the ship, since they had not been included in the purchase.

A few days later, the ship arrived at her builder’s yard of Götaverken for the refit. When this had been carried out, the ship had once again been brought up to the latest standards. For instance, all the public rooms on B-deck had been rebuilt with new textiles and carpets, an air-conditioning system had been installed and even the crew quarters had been freshened up. On Sunday, December 10th 1951, the Swedish flag was hoisted, and the ship set out on her first voyage for the Clipper Line. Sailing from Göteborg, she crossed the Atlantic to the Caribbean to finally terminate the trip at New Orleans. By the end of July 1952, it was once again time to visit the Olympic Games, this time held in Helsinki. Just a month later, it was time for Stella to visit her new homeport – Malmö – for the first time. In late August, she sailed out of Malmö on a Mediterranean cruise. That same summer, a quite amusing incident occurred when the ship called at Calais. 400 beautiful flowers were ordered from ashore, but due to a linguistic misunderstanding, a metric ton of cauliflower was delivered instead. When the original request had gone through though, the unwanted vegetables were taken back.

Two years later, in 1954, it was again time for a refit. However, this time the contract was not given to Götaverken, but to the German yard of AG Weser in Bremen, where Stella arrived on October 8th. The passenger areas were heavily rebuilt, and this resulted in a smaller capacity of just 155 people. But now the ship boasted larger cabins, as well as private bathrooms in nearly each of them.

The years that followed gave good business, and the company made quite a large profit every year. However, 1955 became a year of dramatic incidents. While on a cruise in the Trollfjord, near Lofoten, Stella Polaris was nearly hit by a falling mass of rocks. Fortunately, the rocks missed and Stella escaped unscathed. That same year, a young female passenger decided to end her life by throwing herself overboard near the south coast of Sweden. The rescue attempts failed, and the body was not found until 14 days later at Bornholm. Apparently, the reason for this tragic event was the young woman’s parent’s non-consent to her planned marriage to an Australian soldier.

But in spite of such sad incidents, Stella Polaris remained with the Clipper Line well into the 1960s. In September of 1965, she was taken in for another refit. Both passenger and crew accommodations were modernised, as well as much of the ship’s equipment. The ship’s engines were overhauled, and many components were replaced with new ones. Furthermore, the refrigeration and storage facilities on board were rebuilt to meet new demands of hygiene and efficiency. While the ship went through this refit, thieves managed to sneak on board and get away with art of great value.

When finished, Stella returned to her service, cruising mainly in the Caribbean or the Mediterranean. Since the Clipper Line purchase, Stella Polaris did not make any round-the-world voyages. In October of 1968, Stella was sent to the yards of Kockums, Malmö, for yet another refit. This time, the number of cabins was reduced to just 70 and the crew was therefore cut down to a mere 100 people. But in spite of this refit, Stella Polaris could not quite live up to the latest SOLAS regulations. Another, yet not so extensive, refit was carried out in 1969, but it was soon apparent to the company that it was no longer financially wise to keep the Stella Polaris in service. Instead, she was put up for sale that very year.

On October 23rd 1969, the ship was sold for $850,000 to the International House Co. Ltd. in Tokyo. The new owners’ intention was to put Stella to use as a floating hotel in Japan. On October 28th, the ship left Lisbon flying the Japanese flag. Sailing through the Panama Canal, Stella arrived at Yokosuka on December 13th. When the ship had been made ready for her new purpose, she was tied up at the village of Kisho Nishiura on the Izu-peninsula. The two propellers were removed in order to classify her as a building, not a ship – this to generate lower taxes. The interiors were kept as they were, although worn furnishings were replaced by new replicas. Marketed under the name Floating Hotel Scandinavia, the name Stella Polaris is still on the ship’s bows.

Eventually though, the old vessel’s fortunes began to wane. The hotel business on board Stella Polaris was shut down, while the restaurant remained open. Interested people could come on board for a small fee, and the Scandinavian-style smörgåsbord, locally known as ‘viking’, remained popular. Although far away from her original home, Stella Polaris lived on, but after more than 30 years in Japan, there were people who began to work for a return home to Scandinavian waters.

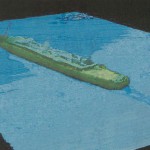

In February 2006, the Stella Polaris was sold to a Swedish company who intended to refurbish the ship and employ her in her by now familiar role as a floating restaurant and hotel. The intention was to move the ship to Stockholm, but before such a voyage could take place the Stella Polaris needed an overhaul, having spent so much time as a stationary vessel. Unfortunately, her condition would bring about her end, as she sank while under tow to a shipyard in Shanghai, China. On September 2nd, 2006, she was lost off Cape Shionomisaki, just south of Nagoya, at a depth of about 70 metres.

| Information courtesy of Anders Bergström and Klubb Maritim, who so kindly provided material. |

Specifications

- 416 feet (127.1 m) long

- 51 feet (15.6 m) wide

- 5,209 gross tons

- Burmeister & Wain diesels turning two propellers

- 15 knot service speed

- Passenger capacity of 200 people

10 thoughts on “Stella Polaris”

Thank you so much for this article. My father served on Stella Polaris from the time Bergen was her home port through all the years with Clipper line and he was among those who took part in the voyage to Japan in 1969. I grew up with Stella Polaris stories as an important part of my family’s history. I will be grateful if anyone can direct me to additional information available or to anyone that might have souvenirs for sale.

Hi, my grandfather worked on the Stella in 1932/33. He wrote a diary of his trip and what he got up to. (Not always one of the ideal crew!) I am looking for more if the crew as my grandfather refers to a friend called Norman. If you have any information I would be grateful. I’m hoping to get his diary published and I have some photos of his journey. It’s not very politically correct but it gives an honest insight to how people saw the native world. Many thanks

My great grandmother Lucy Ricky was hostess on the Stella Polaris during her Mediterranean voyages 1930’s – 1940’s era. She had a summer home in the Virgin Islands. My mother has beautiful black and white photographs of the Stella hanging in her dinningroom along with my great grandmother and the many gentlemen she was hostess to. I myself have beautiful chrystal pen holders with the ship’s name, Stella Polaris engraved in the chrystal that were on the Stella along with stationary. Can’t tell you how happy I am to have found this website with information of what and where she finally came to rest although the information of her final resting place is unfortunate….

Thank you for sharing the tale of your connection to this wonderful ship! Yes, it’s a pity that her long life ended the way it did, but there are always memories and keepsakes such as yours to keep the spirit of Stella Polaris alive and well.

My late aunt and uncle sailed on the Stella Polaris at least once, I believe during the 1930s. They returned with one of the ship’s ashtrays as a souvenir. I have it now. It’s silver, and embossed with an image of the ship sailing through a fiord, with the name M/V Stella Polaris above and the initials B.D.S. below. If such tiny details as the ship’s ashtrays were silver, one can only imagine how luxurious the ship’s passenger accommodations must have been.

I also have a silver ashtray. My parents and sister came to America on her

Thank you for this extensive piece of research on a beautiful ship I remember well from her visits to North Shields on the River Tyne in the late 1940s. Here was a stylish ship with real presence. Fares for five 14-day cruises from North Shields to the North Cape in 1949 ranged from £73 for one of the cheaper cabins up to £236 for a de-luxe suite.

Hi Roy

I’ve just discovered a rather grainy negative of Stella Polaris arriving River Tyne – guess about the years you mention

I worked in Japan from 1973 to 1980 and lived in Tokyo. Sometimes around 1979 I was driving rather aimlessly along the coast south of Tokyo,

Suddenly, I saw white ship with name Stella Polaris. I had a memory of a Swedish ship with that name, so I stopped to have a closer look.

And yes, it was the same ship and it was open for lunch, which was a “Viking”, the name used in Japan for a Swedish style smorgasbord.

It was a fairly japanized smorgasbord, but it was pretty good and it was fun to have lunch aboard that classic ship. And the weather was beautiful,

a crisp autumn day. The only thing I regretted was that I didn’t bring a camera. I think that I must have been the last Swede or even westerner

to have lunch there, the site was not advertised very well.

My father Arthur Bibow Hansen was an Electrician on the Stella Polaris. He never said much about his time on board. However he told me never to become a musician on a ship! After his death I became a trumpet player on the Royal Caribbean line and a trumpet player on the Pacific Princesses….a smaller cruise ship. I sailed from Sidney, Australia to Hawaii then to Nagasaki, Japan and many counties in Asia. I have no photos of Art as I became homeless for a long time. I am in Boulder Colorado now doing very well. If I could find a photo of him on board or in Cuba I would cherish that photo very much.

Sonja