1914 – 1938

Also known as Leviathan

When the German states were united as the German Empire in 1871, the Prussian king was crowned as Kaiser Wilhelm I. Under his and chancellor Otto von Bismarck’s rule, the new nation soon rose to become one of Europe’s greatest powers. Following the Kaiser’s death in 1888, his grandson ascended the throne as Wilhelm II. It was now up to him to continue the work that his grandfather had begun.

Wilhelm professed a deep friendship for Great Britain, where his grandmother Victoria was nearing the end of her reign. Britain was still the superior nation, much because of its dominance on the high seas, but the new Kaiser’s intention was to challenge Great Britain for this position. In order to do so, he had to match their naval and merchant fleets.

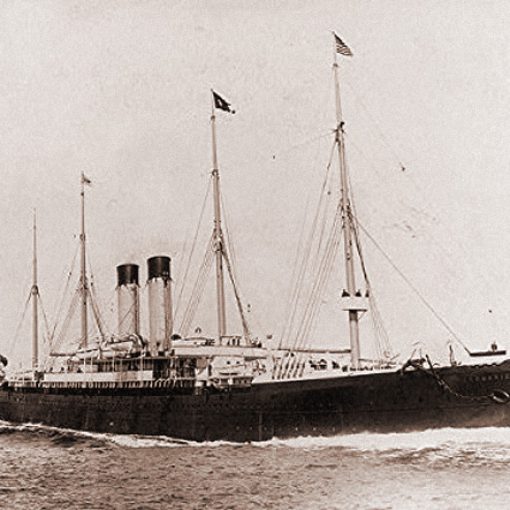

In 1889, Kaiser Wilhelm II attended the Spithead Naval Review, which was held to celebrate Queen Victoria’s 50th year as sovereign. One of the ships participating was the brand new White Star liner Teutonic, which had been fitted as an armed merchant cruiser for the occasion. During an inspection of the Teutonic, accompanied by the Prince of Wales, the Kaiser is said to have uttered: ‘We must have some of these!’ Now, if not before, the Kaiser was determined to challenge Great Britain on the high seas.

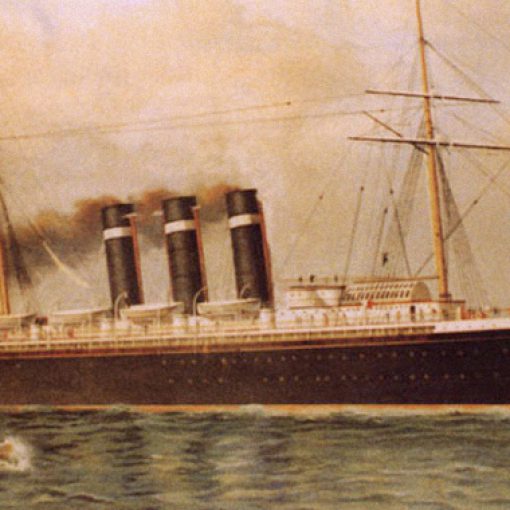

Eventually, Germany’s finest shipping lines began upgrading their fleets with larger, faster and more luxurious ships. Great Britain was still ahead, but when Norddeutscher Lloyd’s express liner Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse entered service in 1897, she left all competitors behind her. Not only was she largest ship yet (except for the Great Eastern,) but she was also luxurious and fast. On her first season, she stole the Blue Riband from Cunard’s Lucania, averaging some 22.3 knots both eastbound and westbound. Suddenly, Britain was no longer on top.

What followed was a great competition of one-upmanship to build faster, larger and more sumptuous ocean liners. These ships were regarded as national symbols, and it was a matter of national pride and prestige to operate the world’s finest liner. On the business end, having the superior ship meant more passengers. These ships were financially viable thanks to the massive emigration from the old world to the new. Larger ships with higher capacities were simply more economical for their owners to run. Ironically, it was the money earned from steerage passengers that went into building and operating these giant vessels. First class was luxurious and what the press focussed on, but it was ironically all made possible because of the emigrants.

Germany’s oceanic might continued with three additions to Norddeutscher Lloyd’s express service – Kronprinz Wilhelm, Kaiser Wilhelm II and Kronprinzessin Cecilie. In 1900, the other large shipping company in Germany, Hamburg-Amerika Line or HAPAG, entered the race with their ocean greyhound Deutschland. When it came to fast ships, Germany dominated completely. However, Great Britain was not out of the race by any means. White Star Line, which had by now left the quest for speed to others, commissioned four new liners from 1901 to 1907. With the Celtic, Cedric,Baltic and Adriatic, they introduced a quartet of unprecedented size and luxury. Furthermore, the Cunard Line was soon to prove their worth as well.

In 1907, the world saw the birth of Lusitania and Mauretania. With this pair, Britain had again surpassed their German rivals. At over 30,000 gross tons, Lusitania and Mauretania became the world’s largest liners. Powered by revolutionary steam turbines, they soon also claimed the title of being the world’s fastest. White Star Line responded a few years later by launching the Olympic, the first liner ever to exceed 40,000 gross tons. She was to be followed by two sisters, securing White Star’s position as a premium line.

But once again, Germany managed to rise above the British. HAPAG’s managing director – Albert Ballin – had already been planning a new trio of ships, all of which would exceed the 50,000-ton mark. The first of them was launched from the Bremer-Vulkan yards in Hamburg as the Imperator in May 1912, just a little more than a month after the Titanic’s ill-fated maiden voyage. By now, the keel for the second ship had already been laid in the yards of another Hamburg shipbuilder, namely Blohm & Voss.

As work progressed on the second ship, a serious flaw was detected in the Imperator’s design. She was top-heavy, and had a tendency to roll and list terribly even in the calmest waters. To remedy this, her funnels were shortened, heavy material on her top decks were replaced with lighter ones and concrete was poured into her bottom. This helped, but the problems would stay with her for the rest of her career. A costly lesson had been learned, and HAPAG was determined not to repeat this mistake on the Imperator’s future sisters.

The second liner was ready to be launched on April 3rd, 1913. Originally, her intended name had been Europa. This had also been thought of for the first sister, but it had been scrubbed in favour of the more nationalistic name Imperator. Once again, such feelings prevailed. When Prince Rupert of Bavaria christened the new ship, the name had been changed to Vaterland. An interesting side note is that the three HAPAG giants were all christened by men, in contrast to the tradition of the age. Kaiser Wilhelm II had done the honours on the Imperator, and would ultimately also do so on the third ship, the Bismarck.

Approximately 40,000 spectators had gathered for the event, and they were now eagerly expecting to see the ship slide down the ways. Careful preparations had been made, so that nothing would go wrong. The momentum of the ship had to be halted almost immediately once it was waterborne, or it might run right into the opposite bank of the River Elbe. Following the ceremony, the launch gear was triggered, and the enormous hull started to move into the water. The attached counterweights did their job perfectly, and the ship came to a halt in the river. Vaterland, the world’s largest ship yet, was born. But, the ship was far from finished. Following the successful launch, Vaterland was towed to her fitting-out basin, where she would be completed with engines, funnels, masts and interior fittings. There was still a lot of work to be done before she could enter service for her owners. And in the meantime, the relations between Great Britain and Germany were growing tense, as was the overall political situation in Europe.

A little more than a year after her launch, the Vaterland was finally ready for delivery. On April 29th 1914, she was completed and handed over to the Hamburg-Amerika Line. The ship had already been vividly publicised, and the company must have been eager to send her off on her maiden voyage across the North Atlantic.

The Vaterland was a true wonder ship. Although she was generally much alike the Imperator, there were several differences between the two German giants. Vaterland was some 2,000 gross tons larger and 39 feet longer than her running mate, thereby claiming the honour of being the world’s largest liner for herself. Unlike the Imperator, Vaterland had not been fitted with a figurehead. Instead, her bow was more subtly decorated with a pair of ornate shields and scrollwork. Internally, there were significant differences as well. On the Vaterland, Blohm & Voss had divided the funnel uptakes, ran them up the sides of the superstructure, and rejoined them at the funnel bases. This resulted in large open areas that would otherwise have been occupied by the uptakes. Thanks to this layout, the interior decorator Charles Mewes had the opportunity to create large public areas.

Certainly, the ship’s interiors did not disappoint. First Class boasted public areas such as a Winter Garden, Social Hall, Grill Room and Smoking Room. There was also an entire row of shops, a travel bureau, bank and a gymnasium and pool complex. One of the finest rooms on board was the First Class Dining Salon, which was adorned by a magnificent circular ceiling mural surrounded by glowing lamps. Vaterland had accommodation for 752 First Class passengers, and the two Imperial Suites and ten Deluxe Apartments were the finest staterooms on the ship. Each of these had a bedroom, a sitting room and a marble bath.

Following the Titanic disaster, safety had been in the focus of shipbuilders, operators and passengers alike. HAPAG had made every effort to make Vaterland as safe a ship as possible, and these safety features were widely publicised by the company. The ship was for example equipped with a full wireless telegraph system, manned for 24 hours a day. Her hull plating and decking was strengthened, and the fore mast had a large searchlight to help detect icebergs and other dangerous objects.

And so, on May 14th 1914, the Vaterland finally left Cuxhaven on her maiden voyage to New York. As the largest ship in the world, she received much attention. As she enjoyed great success, her owners were very satisfied with their new flagship. There was one slightly disgracing incident though, when the ship’s captain attempted to back out from her Hoboken pier without the assistance of tugboats. To handle such a large ship in the Hudson River proved quite difficult, and the ship nearly ran into the piers on the opposite side.

But, this event was of little importance when compared to what was to happen a few months later. On June 28th 1914, the shots of Sarajevo became the spark that would soon ignite the First World War. Austria-Hungary’s crown prince Franz Ferdinand had been murdered, and a month later Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia. Through a number of alliances, Germany then declared war on Russia, France and Belgium. Following their own alliance obligations, Great Britain soon declared war on Germany.

The European nations had feared this moment for years, and each had plans ready to quickly requisition merchant liners for war service. But the timing was terrible for Imperial Germany, and only five ships made it back home for the necessary conversions. 37 potential ships had been interned in neutral ports, and one of these was the Vaterland. After having made only seven crossings, the Vaterland was in Hoboken in the middle of her fourth North Atlantic round trip when the war broke out. On July 31st, she received orders to remain in New York and await further instructions. Four days later, Great Britain’s declaration of war against Imperial Germany came, and the Vaterland was ordered to stay at her Hoboken pier.

What followed was three years in uncertain limbo. Officially, the ship was still awaiting orders. The crew had all been offered to return to Germany, but more than half of them had chosen to stay with the ship. As time went by, they grew accustomed to their new home in New York. Crewmen swam in the Hudson River in the summer, and ice-skated on it in the winter months. During the early stage of the war, a pro-German sentiment was widespread in the United States, and the German-American community used the ship to arrange banquets, balls and concerts to raise funds for the German Relief Effort. But as the war raged on, the tendency gradually shifted to an anti-German opinion, and the Vaterland was declared ‘restricted territory’. Many Americans saw the ship as an espionage nest, and only a small crew was kept on to maintain the ship as good as they were able to.

Albert Ballin, the mastermind behind the Hamburg-Amerika Line and its giant trio, saw the war as insanity. Fearing for his beloved ships, he tried to have the Vaterland turned into a neutral ship that would carry relief supplies to Belgium. But his efforts would be in vain. On April 2nd 1917, President Woodrow Wilson delivered his ‘War Message’ in a special session of Congress. It was evident that the US was about to enter the war against Imperial Germany and her allies. Facing the threat of seizure, the skeleton crew on board the Vaterland was not ready to just give away the great ship to a potential enemy. Instead, they sabotaged the engines and boilers.

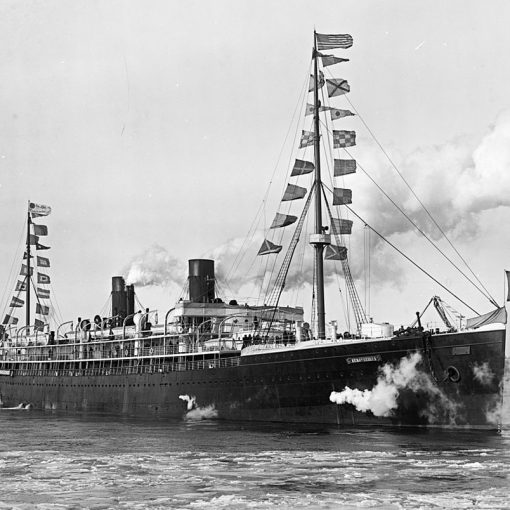

Then, on April 6th 1917, Congress overwhelmingly passed the War Resolution, which brought the United States of America into the Great War. The Vaterland was seized by American authorities, and the crew was taken to Ellis Island where they were offered American citizenship. But with the damaged engines and boilers, the ship had to be repaired in addition to being converted for war duties. Nevertheless, three months later she had been transformed into the US Navy transport Leviathan. Through a quirk of fate, her new task was now to help defeat her one-time creators.

And so, the Leviathan entered wartime service on the North Atlantic, ferrying troops to the European battlefields. Her contribution was of great importance, carrying a total of more than 100,000 soldiers on 19 voyages. At one point, she carried 14,416 souls – at the time the largest number ever to be transported by a single ship. In 1918, she also had the honour of carrying General Pershing across the North Atlantic. By now, it was evident which side of the war would be triumphant. Albert Ballin, who had opposed the war since the beginning, realised that the end was near and that his company would lose their ships, not least his giant trio. Devastated, he took an overdose of sleeping pills on November 9th 1918. The next day, he died in a Hamburg hospital.

As The Great War came to its end, it was now up to the victorious nations to dictate the terms. For Germany, the Versailles Treaty was a disaster. Imperial Germany was ordered to surrender nearly their whole merchant fleet, to be handed over to the victors as war reparations for tonnage sunk by German forces. While the Imperator was given to Cunard and renamed Berengaria, the still uncompleted Bismarck was handed over to White Star Line and was to be completed as the Majestic. The Leviathan was handed over to the US Shipping Board, but no decision regarding her future was made. Instead, she was laid up at New York in September 1919.

She remained tied up at her Hoboken pier for more than two years, while politicians debated on what should be done with her. In the end, it was decided to place her with the newly formed United States Lines as the flagship of the US merchant fleet. In 1921, she was sent to Newport News to be converted for passenger service again. The contract of supervising the massive task was given to the recently formed Gibbs Brothers Inc, headed by naval architect William Francis Gibbs who 30 years later would become famous for designing the speed queen United States. Gibbs’ first order of agenda was to obtain the ship’s blueprints, which was needed to do the conversion. But, when he contacted the German builders, they demanded $1,000,000 for them, since the plans had not been included in the Versailles Treaty. Unwilling to pay such a sum, Gibbs instead went back to Newport News and started the immense task of taking careful measurements of the entire ship, in order to create his own set of blueprints.

But this was not the only challenge that had to be overcome. The Leviathan’s war service had taken its toll, and her layout had to be virtually redesigned. Close to 150 draftsmen and thousands of workers were put to the test, setting out to bring the ship back to her pre-war splendour. The original electrical wiring was torn out and replaced completely, and much of the plumbing on board had to be redone. Steel was reinforced, the engines were restored and the passenger areas were virtually rebuilt from scratch. Following the $8,000,000 refit, the Leviathan emerged as a new vessel in 1923.

On June 19th 1923, the Leviathan set out on her sea trials for her new owners. These were a success, with the ship reaching an impressive average speed of 27.48 knots. She had also been remeasured at 59,956 gross tons, but it should be noted that these figures had been calculated after American standards, which differed a great deal from those applied to British ships. But in these days when being the largest, fastest or most luxurious was so important to attract passengers, the shipping companies needed all the publicity they could get. So, although White Star’s Majestic was in reality a larger ship than the Leviathan, United States Lines would often market her as ‘the largest ship in the world’, based on her American gross tonnage.

And so, the new flagship of the American Merchant Marine set out on her second maiden voyage on July 4th 1923, leaving New York bound for Southampton. With great margin, she was the largest merchant ship ever to fly the Stars and Stripes. She quickly earned great popularity, especially among American tourists, who wanted to sail on an American liner. In this aspect, being the only large American ship certainly was an advantage. But, the lack of a similar running mate resulted in large gaps in her sailing schedules. Furthermore, when the US enacted more restrictive immigration laws, the giant pre-war liners became somewhat of anachronisms.

Another problem was the American prohibition of alcohol. As an American-registered vessel, the Leviathan counted as an extension of US territory, and as a result prohibition applied on board the ship as well. Being a ‘dry ship’ certainly held the Leviathan back in the 1920s. In addition, the service on board was reputed poor and not equivalent to that on British or French liners. True or false, such common believes did not help the Leviathan’s reputation.

Nevertheless, she retained a loyal following, and the official figures indeed seemed impressive. During 1926, she averaged 1,300 passengers per voyage, making her the second most travelled-on liner on the Atlantic that year, but 1,300 people were not that much on a ship with a capacity of nearly 3,000 souls. She did show increases in her passenger records every year from 1923-1927, but these were lean times for liners, and she was losing money for her owners. Being popular was not the same as being profitable. Leviathan was an expensive ship to operate, with high American wages plus union and fuel costs. From time to time, the ship had to rely on so-called temporary labour, college students who would sign on to get to Europe and then jump ship when they got there. Or they would work summers only, for a labour-intensive tenure.

Later in the ‘20s, the prohibition laws were somewhat eased and the Leviathan was given permission to serve alcoholic beverages once she was outside US waters. This opened up opportunities for other duties, and the company soon started sending the Leviathan on ‘booze cruises’ to nowhere, trips without destination with the only purpose of giving people the opportunity to consume alcohol legally. But the financial situation at the time was getting worse and worse, culminating in The Great Crash in 1929. Very few could still afford an ocean voyage, and the Leviathan started to slip into the red. In 1931, her tonnage was reduced to an incredible, and often questioned, 48,932 gross tons. This was done through manipulation of measuring regulations, in order to save money on harbour dues which was paid according to size.

To many, this was a sign of the ship’s impending end, and in 1932 she was laid up. Although well known and popular, she had been one of the least successful liners during the 1920s. In 1934, when the economics had recuperated slightly, the Leviathan made four more voyages to Southampton, but was again laid up at New York in September that year. In her later years, a number of structural weaknesses, for instance a series of cracks in her superstructure, had been detected.

Leviathan remained laid up at New York until December 1937, when she was sold for scrap to Metal Industries Ltd., Rosyth and T. W. Ward, Sheffield. She remained in New York over the New Years, but left for Rosyth under her own power on January 26th 1938. She arrived there on February 14th, and the work on breaking her up would soon commence. It is interesting to ponder over what might have been, had she survived just a year longer. With her enormous capacity and high speed, she would have made a valuable troop transport during World War II. But, it was not to be, and the largest American merchant ship ever met her end at the scrap yard instead.

Specifications

- 948 feet (289.6 m) long

- 100 feet (30.6 m) wide

- 54,282 gross tons

- Parsons steam turbines turning four propellers

- 23.5 knot service speed

- Passenger capacity of 3,909 people