1954 – 1982

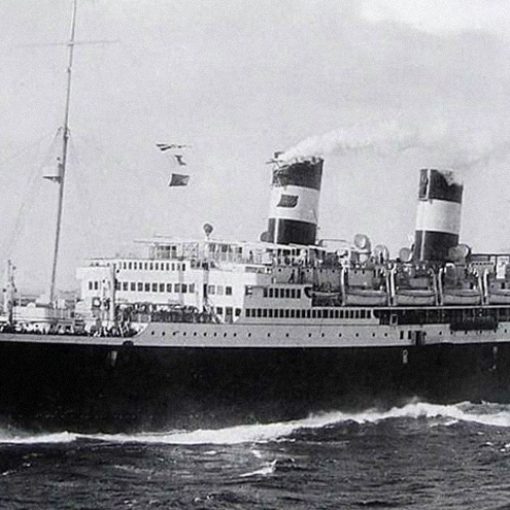

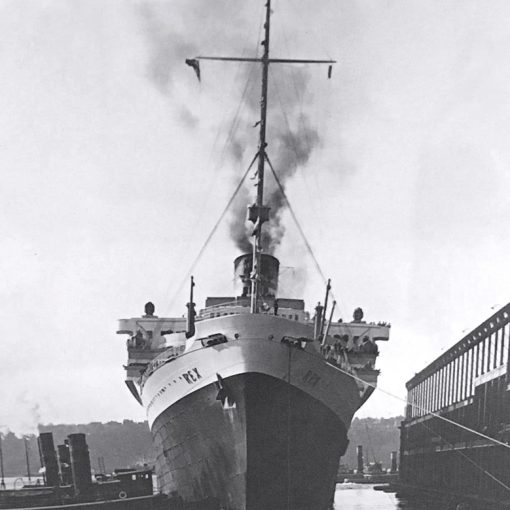

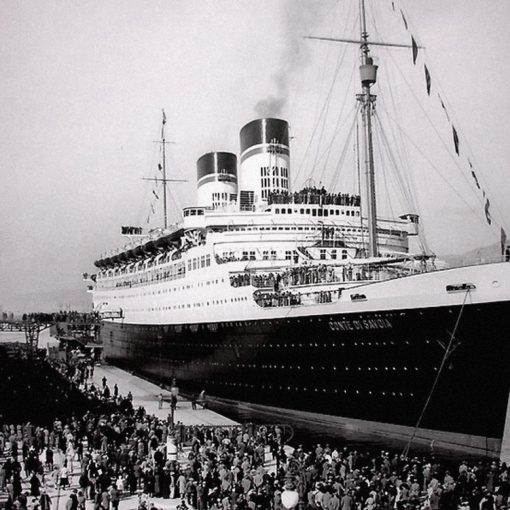

When World War II was over, the Italian Line stood without their two most prestigious liners. All that remained of the former Blue Riband-champion Rex was a capsized, burnt out and derelict hulk south of Trieste. British bombers had finished her in 1944, while the Conte di Savoia had been set afire and destroyed by the Nazis the previous year. As Italy belonged to the states that had lost the devastating war, it would take a long time before the country, and for that matter the Italian Line, would recover.

The dust from the war did not seem to settle until the early Fifties. By then, the financial situation for most countries pointed upwards. The merchant fleets also seemed to regain power as the ships that had served their countries during the duration of the hostilities had been returned from their Admiralties to serve passengers, not soldiers. By this time, the Italian Line had started planning two new liners for the trans-Atlantic run. These ships were not to be the same size the Rex and the Conte di Savoia had been, or not as fast. Planned to be around 30,000 gross tons, these liners would catch attention because of luxury and style – two things the Italians certainly know how to deal with.

The first of the two sisters entered service in early 1953. She was called Andrea Doria after a famous Renaissance sea-hero. When she arrived in New York she received a gala in the harbour reception. Indeed, Italy and the Italian Line had recovered from the now more and more distant war.

The second sister was, just as the Andrea Doria, built at the Ansaldo Shipyards in Genoa. She was launched and christened Cristoforo Colombo in 1953, and completed and ready for her maiden voyage in 1954. On July 15, she cast her moorings and left Genoa for New York. She too was cordially welcomed upon arrival in America. She was the largest ship in merchant service in Italy – at 29,191 gross tons she precisely beat the Andrea Doria’s 29,093.

The most terrible blow to the Italian Line occurred on July 25, 1956. As the Andrea Doria was inbound to New York in dense fog, commanded by Captain Piero Calamai, another liner was outbound for a crossing to Göteborg. This was the Swedish American Line’s Stockholm that was under the command of Captain Gunnar Nordenson. The two ships spotted each other on the radar, but as they came closer they had decided to pass each other on two different sides. This resulted in the two vessels turning the same way, towards each other. In a cloud of sparkles, the two ships crashed together. The Stockholm seemed to remain afloat, but the Andrea Doria had immediately taken on a dangerous list to starboard. She was mortally wounded and sunk in the morning hours of the 26th.

The losses of life had not been heavy. All the people that had survived the crash were rescued by the Stockholm and the grand CGT-liner Île de France that happened to be in these waters. Still, the Italian Line was mortified. They had lost their fabulous lady of the seas, and the public had lost their faith in them. All that remained was the Cristoforo Colombo.

The Cristoforo Colombo was the bigger ship, but as Andrea Doria had came out first and set the new standards, the public seemed to be more attached to her. But she was just as luxurious as her sister with her grand first class ballroom and splendid dining room. One of the few ultra-luxurious suites – an ‘Apartment Deluxe’ – was prized at $1000 per person in peak summer times for an Atlantic crossing.

The Cristoforo Colombo soon settled in her own Atlantic career – without the Andrea Doria as her big brother, or ‘big sister’. Both passengers and crew became fond of her. The dockers at New York also appreciated this streamlined Italian marvel, even though they sometimes were on a strike, letting the ship dock herself – a procedure that could take hours and hours. On February 5, 1957 such a strike was on when the Cristoforo Colombo arrived at New York harbour. She had to go in-between the piers herself, using her engines with the finest precision. When she came in too close for engine manoeuvring, she lowered her anchor, attached it in the harbour bottom and pulled the chain in, thus moving the whole liner closer to the pier. She repeated this until the ship finally was safely moored. This was a time-consuming procedure, but as strikes were common, the officers had learned how to handle the problem quite quickly.

In 1960 the replacement for the Andrea Doria came. She was over 30,000 gross tons and was called Leonardo da Vinci. Again, the Italians could be proud to boast two express liners from the Mediterranean to New York. Cristoforo Colombo and Leonardo da Vinci were called express liners in spite of their 23-knot service speed. The required speed for the coveted Blue Riband of the Atlantic, which was held by the American liner United States, was approximately 35 knots. But there were many ships with a service speed below 20 knots, so 23 knots should be looked upon as quite fast, therefore the epithet ‘express liners’.

Four years after the introduction of the Leonardo da Vinci, the Cristoforo Colombo was given the most honourable task. In the spring of 1964, the ‘Pietà’ from the Vatican was carried on board her to New York for the World’s Fair. ‘Pietà’ was put in a crate that was filled with plastic foam. The crate was lowered onto a rubber base in the first class pool where least damage was likely to happen to it. Special safety precautions were made when the actual loading occurred as well. The Cristoforo Colombo had been put in dry dock so that she would not move an inch and thereby perhaps jeopardise the crate and its content. Only easily removable snap hooks secured the crate so that it could be released easily in case of accident. In case the Cristoforo Colombo would sink during the voyage, the crate had been floatable. When at New York it was lifted by a heavy-lift floating crane onto a barge that was put alongside the liner.

The Cristoforo Colombo and the Leonardo da Vinci were kept as the flagships and the prime Italian ships on the North Atlantic until 1965 when the brand new Michelangelo arrived. Shortly after, her sister Raffaello followed, and the Cristoforo Colombo was taken out of trans-Atlantic service. Instead, she replaced the two smaller Saturnia and Vulcania on the Adriatic trade. She was painted entirely white in 1966 in order to match with the other ships in the Italian Line who had abandoned black as hull-colour.

In 1973, the Cristoforo Colombo was taken out of the Adriatic service. She was supposed to go on the South American run to replace the Giulio Cesare that had suffered some serious mechanical problems. She stayed here until 1977 when it was realised that it was utter futility to keep the Cristoforo Colombo running. Ships like her had become very uneconomical to run. She was sold to the country of Venezuela, but they had no intention to keep her going, but used her as an accommodation ship for workers at Puerto Ordaz. In 1981 she was sold to Taiwanese scrappers. They towed her across the Pacific, but upon arrival at Kaohsiung they towed her to Hong Kong, hoping someone there would express interest in buying the ship. However, no one appeared and in the autumn of 1982 she was towed back to Kaohsiung where she was scrapped.

Specifications

- 700 feet (213.8 m) long

- 90 feet (27.5 m) wide

- 29,191 gross tons

- Steam turbines powering two propellers

- 23 knot service speed

- Passenger capacity of 1,055 people

12 thoughts on “Cristoforo Colombo”

I took the Cristoforo Colombo from New York to Malaga Spain with a stopover in Lisbon in January 1973. I was told my our steward Marcello, that it was to be the last trip as the ship had tipped more than 45 degree in a storm. It was going to be sent to the Caribbean after that. I had a student ticket ($150.00 CDN) and a birth in the ‘bowels’ of the ship with bunk beds and pipes over our heads but it was the best trip ever! Food and staff were great.

I came to New York with my Mom, Dad and older Brother June of 1955 from Napoli. I will never forget that trip as we were in 3rd class. I was 8 years old and my Mother held my hand for the complete trip. My brother was 14 and he had the run of the ship and had a great time. Coming into New York Harbor and seeing the Statue of Liberty was exciting and amazing for everyone on ship.

My family and I came to the US in November 1954 on the Cristoforo Colombo!

My grandmother came to the US with my aunt and uncle in June 1956 on the Columbo from Napoli and I am trying to find the passenger list to show my Dad.

I was aboard the Christoforo Colombo one year after the Andrea Doria collided with the Stockholm. I was seven at the time. I remember the ship stopping early in the morning at a large white buoy south of Nantucket. Everyone on the ship was on the port side looking at that buoy as the sun rose, many weeping.

Is there anyway to get a manifest of the passengers from the Cristofer Colombo from August 1967 from New York to Naples?

I and my family emigrated to the States on the Cristoforo Colombo in 1956. Great adventure for a 16 yr. old kid. I’ll never forget the view of Manhattan as the ship entered the Hudson River. Sixty-six yrs. ago this year.

My family n I came here from Italy in 1954 . It was September. Wish I had some information about , was this the first trip to New York? Also I wish I had some pics! We use to travel back n forth to Italy every 2 or 3 years n it was always on this linear.

The Cristoforo Colombo continued in the Trans-Atlantic trade through at least 1968. I travelled from the US to Italy on her in both 1967 and 1968, returning to the US on the Leonardo DaVinci in 1967 and the Raffaello in 1968.

Can you tell me how much a ticket cost? My mother was on that ship from Genoa to NYC in the early 1960s and I’m really interested in knowing this.

Can you send me a few pictures of the Cristoforo Colombo for my dad? He came to America on that ship in 1957.

Your article claims that C. Colombo stopped travelling across the ocean in 1965.I came to Canada on that ship, Halifax, Nov.22,1967