1906 – 1914

In the early 1900s, the Canadian Pacific Railway Co. was indeed one of the foremost companies operating steamships across the globe. The company’s global system of transportations ranked as the largest in the world. Steamers sailed across the North Atlantic from Britain to Eastern Canada and from there, rails stretched west all the way to the Pacific port of Vancouver. Here ships continued the relay, crossing the Pacific Ocean to reach the Orient. Canadian Pacific enjoyed immense success and popularity among the travelling public, with their famous fleet of Empress-liners as a trademark.

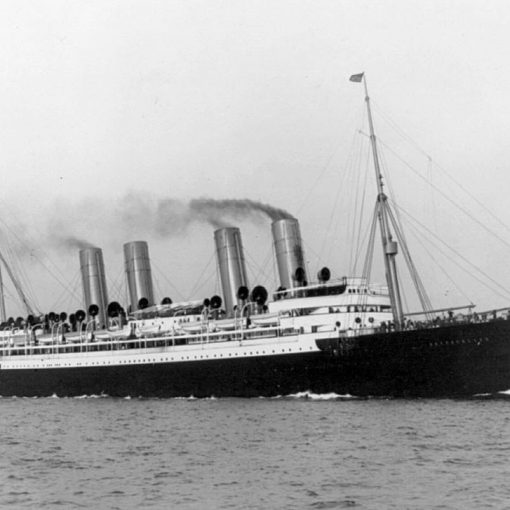

One of these liners was the Empress of Ireland. She and her sister ship, Empress of Britain, were both commissioned in 1906 for Canadian Pacific’s Liverpool-Quebec route. Built by the Fairfield Shipbuilding & Engineering Company of Glasgow, the two sisters were more or less identical in appearance, although the Empress of Ireland beat her older sister in size by just a glance – she was two tons larger. The two vessels had originally been planned as the Empress of Austria and Empress of Germany, but for some reason the names were changed at an early stage. The pair had been designed with a mail contract in mind, so it was crucial that they were able to maintain their schedule even in rough weather. They had to be able to average at least 17 knots during each crossing, and were therefore constructed with a higher freeboard than other ships at the time.

The Empress of Ireland was launched by Mrs Alexander Gracie on January 27th, 1906. Five months later, on June 29th, the day had come for the new Empress to set out on her very first voyage across the North Atlantic. She soon proved to be a reliable ship, meeting every expectation of her owners. With her 14,191 tons and 17-knot service speed, the Empress of Ireland was one of the largest and fastest ships operating on the Canadian run. Yet she was not very famous, at least not if you compare her with some of her more fashionable contemporaries on the more southerly Liverpool-New York route. In 1907, Cunard introduced their speed queens Lusitania and Mauretania, and four years later, White Star Line’s magnificent Olympic entered service. But with this in mind, the Empress of Ireland was truly a fine liner, with airy public areas and even a five-piece string orchestra on board to serenade the first class passengers during dinner time.

The Empress of Ireland’s service within the Canadian Pacific Railway Co. went on with neither mishaps nor miracles. Her older sister Empress of Britain broke the speed record for the run between Father Point and Liverpool with a crossing of 5 days, 8 hours and 18 minutes in 1907, but the Empress of Ireland was never to possess any such honours. It seemed that Canadian Pacific were perfectly content with letting the Empress of Britain bathe in the glory. However, one interruption in the Empress of Ireland’s otherwise steady service came in July of 1913, when she participated in the Mersey Royal Review of merchant and naval vessels by King George V and Queen Mary. After this brief break, it was back to her somewhat anonymous service again.

Tragically, as history would have it, the memory of the Empress of Ireland was to be associated with disaster, just as with the Titanic, Lusitania and Andrea Doria – to just mention a few. On May 29th 1914, the Empress of Ireland left Quebec at half past four in the afternoon with a total of 1,477 people on board. Travelling down the St. Lawrence River, the Empress – under the command of Captain Henry Kendall – encountered heavy fog when she was nearing the mouth of the river that same evening. Later that night, when it had already become the 30th of May, the Empress’ lookout reported spotting an incoming ship on the ship’s starboard side. The rules to be applied when two ships meet in bad visibility were not very complicated: When meeting head on, each ship was to turn to starboard and pass the meeting vessel ‘port-to-port’. But if the two ships were on a ‘starboard-to-starboard’ course, this was to be maintained due to the risk of collision.

When the two ships were approaching in the night, the fog suddenly became much denser. Captain Kendall ordered the Empress of Ireland stopped and her engines put astern to give the meeting ship more manoeuvring space. He then gave three blasts with the ship’s whistle to announce his action. Tragically, the crew on board the oncoming ship – which was the Norwegian collier Storstad – had taken actions to pass ‘port-to-port’. Making their starboard turn, the crew of the Storstad put their ship directly across the path of the Empress of Ireland. Emerging from the thick fog, the Storstad’s bow crashed into the starboard side of the Empress. Disaster was now a cruel fact.

The Empress of Ireland had been holed above and below the waterline just where the engine room was situated. It took only a short moment before the engine room was flooded, making it impossible for the crew to operate the ship’s watertight doors. It also rendered the Empress powerless to move, thus making any plans of beaching the ship unexecutable. In addition, the Empress’ electrical power was rapidly fading, and only one S.O.S.-call could be sent before it went out completely.

The whole course of events that followed after the collision occurred during the brief time of only 14 minutes. The Empress of Ireland had taken on a serious list to starboard immediately after the impact, and it grew worse by the minute. Open portholes in the ship’s hull made matters even worse – as soon as they went under, more water was rushing in at a horrifying pace. For many of the passengers who were asleep in their cabins, there was barely time to understand what was happening before it was all over. A small number of people, mostly from the first class cabins situated on the upper decks, managed to get out on the boat deck. But once there, things did not look much brighter. Some ten or eleven minutes after the collision, the Empress of Ireland violently lurched over on her starboard side, throwing hundreds of people – including Captain Kendall – into the freezing waters of the St. Lawrence River. Hundreds of people were clinging to the side of the ship, which was now lying completely on its side in the water. For a short moment, it seemed as if the ship had gone aground and would stay in this position. But suddenly, the Empress of Ireland’s stern rose slightly out of the water, and then the ship slipped beneath the cold waves. Hundreds of people were left in the icy waters, and only four lifeboats had managed to escape the sinking vessel.

One of the lucky souls that were pulled into one of these lifeboats was Captain Kendall. Realising his responsibility, he immediately took command of the craft and started organising the rescue operations. Pulling survivors from the water, the lifeboats offloaded them on the ship that had crashed into the Empress. The fog was still very dense, and Captain Kendall did not yet know the name or nationality of the ship that had sunk his command. After several rescue runs with the lifeboats, no more survivors could be found and Captain Kendall gave up the search. He then returned to the Storstad, which was badly damaged but still afloat.

The following month a Court of Enquiry was held to settle the question of blame in the disaster. Heading it was Lord Mersey, who had also been in charge of the investigations surrounding the Titanic’s sinking two years earlier. Calling 61 witnesses, the Court put the main blame on the Storstad, because it had taken a dangerous course to pass ‘port-to-port’ of the Empress. The Norwegians disagreed and maintained that Captain Kendall was to blame – they meant that by going astern, he had put his ship in the way of the Storstad. Nevertheless, the Norwegian company of A. F. Klaveness was sentenced to pay Canadian Pacific’s damage claims. Unable to meet the liabilities, the Storstad’s owners were forced to sell her to afford the claims.

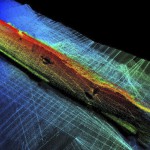

Today, the Empress of Ireland remains at the location where she once went down in the St. Lawrence River, five miles east of Father Point. A red ‘wreck’-buoy still marks the spot. There have been numerous visits to the sunken liner, which lies at a depth of about 130 feet, or 40 meters. She lies on her starboard side with a gaping hole on the port side of the hull. This hole was blasted by Canadian Pacific shortly after the sinking, in order to retrieve a precious $150,000-cargo of silver bullion and the mail going from Canada to England. The hole now serves as divers’ entrance into what was once the ship’s first class dining room.

The most terrifying part of the Empress of Ireland’s wreck is the place that is commonly known as ‘The boneyard’. This is in fact the stewards’ dormitory, and it contains the bones of the sixty stewards who were sleeping there at the night of the disaster. Lying in a ghastly rubble, these bones are a horrifying reminder of that hellish night of May 30th, 1914.

Specifications

- 570 feet (174.1 m) long

- 65.6 feet (20 m) wide

- 14,191 gross tons

- Quadruple-expansion engines turning two propellers

- 18 knot service speed

- Passenger capacity of 1,580 people