1903 – 1940

By 1902, the Bremen-based shipping company of Norddeutscher Lloyd (North German Lloyd) was in the midst of a great project. It had started back in the 1890s, when the German Kaiser decreed that he wanted Germany to be the prime power on the high seas. This led Norddeutscher Lloyd to commission what would be the world’s first four-funnelled steamer – the Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse of 1897. This ship had not only been the largest of its time, but also the fastest, which she proved by capturing the coveted Blue Riband from the Cunarder Lucania. Great Britain, who up until this event had been supreme on the world’s waves, was left behind in a state of shock. It would take them ten years before they could once again pass the Germans with British ships.

So when the 20th century began, the foremost ships on the North Atlantic were German. The great success of the Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse soon led another German company – the Hamburg-Amerika Line (HAPAG) – to order their very own supership. Introduced in 1900, this ship was named Deutschland and her mission was to win the Blue Riband from the Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse. She succeeded in doing so, but at a very costly price. The great engines that provided the Deutschland with her power also caused her to vibrate and shudder violently when steaming at high speeds. Nevertheless, she was still the speed queen of the North Atlantic. But HAPAG would after this never operate a Blue Riband-holder. The company’s managing director, Albert Ballin, decided to go for large and comfortable ships rather than swift ones.

But the board of the Norddeutscher Lloyd felt differently. Their aim was still to own and operated the fastest ships on the North Atlantic. Therefore, they soon ordered a second ship as a complement to the Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse. Named after the crown prince of Germany, this second ship was called the Kronprinz Wilhelm. Decorated in style with her predecessor, the Kronprinz became a great success in all but one respect – her speed. Although she did break the Deutschland’s westbound record time, the HAPAG ship soon managed to better the time and regain the honours. The Kronprinz Wilhelmhad failed in her quest for speed.

However, the two Norddeutscher Lloyd four-stacker were a great success among the travelling public. The upper class enjoyed them because of their splendid and luxurious decorations, and the not so financially independent people travelling in steerage favoured ships with many funnels. The general opinion within this social group was that the more funnels a ship had, the safer it was. What could then be more safe to cross the Atlantic on, than a massive ship with four large funnels?

The European emigrant market was booming, and soon it was clear to Norddeutscher Lloyd that yet another large ship would be a smart move to make in these times of economic welfare. So they once again turned to the Vulkan Shipyards of Stettin, that had earlier built both the Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse and the Kronprinz Wilhelm, as well as the Deutschland.

Work was soon under way to complete the third vessel to join NDL’s group of express steamers. The first two sisters had been quite similar in appearance, length and tonnage, but the new vessel would be considerably larger than her older siblings. In fact, the Kaiser Wilhelm II was the first German ship to exceed the size of the famous Great Eastern. But, although some 50 feet longer and 5,000 tons larger, she still looked a whole lot like her future running mates. Just like on the Kaiser and the Kronprinz, the funnels on the new sister were grouped in two distinctive pairs. This feature had by now become somewhat of a German trademark on the North Atlantic.

On August 12th 1902, the latest addition to the NDL fleet was launched and christened Kaiser Wilhelm II, after Germany’s current monarch. The launch went without mishaps, and a giant team of carpenters, electricians, plumbers and other workmen could now start the task of fitting the ship out. The man who had designed the interiors of both the Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse and the Kronprinz Wilhelm was also chosen to do the decoration of the Kaiser Wilhelm II. His name was Johannes Poppe. In tradition with his work on the earlier Norddeutscher Lloyd-liners, Poppe created an environment surrounded by so much luxury that it was thought by some that it was too much. Using such materials as rich woods and marble, Poppe designed airy public areas with high ceilings and rich ornate carvings. The result was a ship that outmatched her older sister, at least when it came to the interiors.

But the question of the Kaiser Wilhelm II’s speed still remained. After the Kronprinz Wilhelm’s failure to regain the Blue Riband for Norddeutscher Lloyd, all hope now stood to the new ship. Eight months after her launch, the Kaiser Wilhelm II had been fitted out and was ready for her maiden voyage. On April 14th 1903, she left Bremen with New York as final destination, calling at Southampton and Cherbourg along the way. But those who had a record crossing in mind soon had all their hopes dashed. With a service speed of around 23 knots, the Kaiser Wilhelm II could still not match the Deutschland’s westbound average speed of 23.15 knots.

Another disappointment with the new Kaiser Wilhelm II was that she, like the Deutschland, had a tendency to vibrate when she was steaming at high speed. As an attempt to remedy this fault, the ship was taken in to be given a new set of propellers in 1904. Luckily for Norddeutscher Lloyd, the vibration problems on the Kaiser Wilhelm II were not as severe as those on the Deutschland. Not only did the new propellers reduce the vibrations considerably, they also made the ship run more smoothly and steadily.

With the vibration-problem cured, the quest for the Blue Riband was once again on. In June 1904, the Kaiser Wilhelm II managed to set a new eastbound record with an average speed of 23.58 knots. The battle was thus partially won, but the ship would never have the westbound record – it seemed as if she was simply not up to the test of the conditions on a westbound crossing. However, her eastbound record would be unthreatened until the arrival of Cunard’s Lusitania in 1907.

But, being one of the largest and fastest ships in the world earned the Kaiser Wilhelm II fame, and she became a popular part of Norddeutscher Lloyd’s trio of express liners. In 1907, this trio became a quartet when a fourth vessel – the Kronprinzessin Cecilie – was delivered from the shipyards of Vulkan. These four ships soon had won a reputation of grandeur, reliability and above all – speed. It did not take long before they were commonly known as ‘The Four Flyers’.

Enjoying this great reputation, the Kaiser Wilhelm II continued serving Norddeutscher Lloyd on the North Atlantic run. She was not only one of the largest and fastest vessels on the high seas, it seemed as if she had been blessed with a great deal of good fortune, as she was seldom involved in any accidents. However, in 1907 she had to be withdrawn from service for several months after having sunk at her pier in Bremerhaven during coaling operations. After repairs had been made, the ship was again back on the run. She did not suffer from any bad luck again until June 1914, when she was involved in a collision which resulted in her absence from the waves during the early summer that year.

On July 28th 1914, the Kaiser Wilhelm II set out on what was to be her last commercial crossing. While en route to New York, the First World War broke out in Europe. This war had been anticipated for quite some time, and most nations had had their ships constructed with a possible conflict in mind. Nearly all the larger steamers had been built so that they in the event of hostilities could contribute to the war effort in some way or another.

But the outbreak of war came at a very bad moment for Germany. Not many of the nation’s vessels managed to get back to Germany for conversion, and were instead interned in foreign ports. One of the greatest losses was surely HAPAG’s brand new 54,000-tonner Vaterland, which was interned in New York. But also two ships of the Norddeutscher Lloyd express quartet soon found themselves in foreign hands. The Kronprinzessin Cecilie was interned in the port of Boston after a dramatic game of hide-and-seek on the North Atlantic, and the Kaiser Wilhelm II was retained at her NDL pier in Hoboken, New Jersey.

And in New Jersey she remained, the Germans probably figured that an American port was quite a safe place for one of their finest ships. But after three years of fighting in Europe, the United States entered the war. This was indeed a terrible blow for Germany, who now saw all their American-interned ships seized and used against them. The Kronprinz Wilhelm had by now also been interned in the US after a successful raiding cruise of the seas.

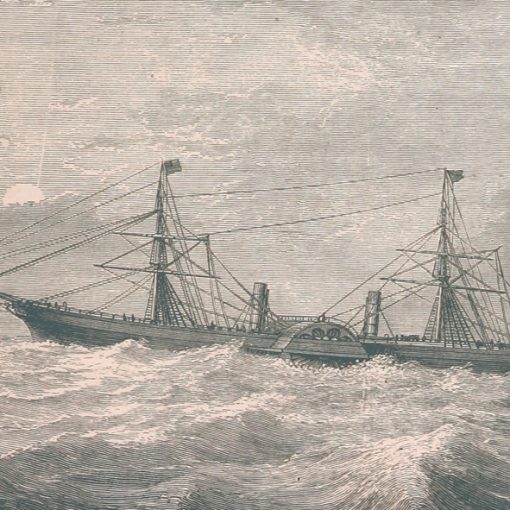

The Kaiser Wilhelm II was of course no exception to the rules of war. In April 1917, she was seized for use as a troop transport, and was renamed USS Agamemnon for this purpose. Now fighting her creators on their enemies’ side, she started doing trooping duties between America and Europe. But by now it seemed as if she had started suffering from bad luck. While taking part in a trooping convoy from New York to Brest in October 1917, the Agamemnon was struck amidships by her sister ship Kronprinz Wilhelm, which had been renamed USS Von Steuben. Four months later, she again sank at her pier during coaling. But her services as a troopship was badly needed, and this time she was returned to service in a matter of days.

Continuing her allied service as a troop transport, the Agamemnon would soon be involved in more mishaps. Almost as if reluctant to cut off her bonds with her sisters, the Agamemnon was again involved in an incident with another ex-NDL express liner in June 1918, this time with the ex-Kronprinzessin Cecilie, who had been renamed USS Mount Vernon. With more than 5,000 people on board, the Agamemnon and Mount Vernon nearly collided with each other at night. Yet the collision was avoided at the last minute, and the two ships could continue their war tasks. Later on the Agamemnon had to be laid up for two months for repairs, after having sustained damage in rough seas.

In 1919, the war was finally over. Germany had been defeated, and the victorious warlords had delivered their unconditional sentence. The entire German merchant fleet was given away as war reparations for sunken vessels. Only the old speed queen Deutschland remained in German hands, but that was because the poor state she was in – there was no one who wanted her.

The three sisters Agamemnon, Mount Vernon and Von Steuben were all given to the United States Shipping Board. The Agamemnon was used for repatriation voyages until 1920, but then there was no task for her and she was laid up together with the Mount Vernon in the Patuxent River, in the backwaters of Chesapeake Bay.

There the two ships remained through the years. They had both been run hard during the war, and neither of the two ships was in a very favourable condition. Yet there were still plans of further service for the to ex-Germans. Some felt that they could be refurbished and used as passenger liners once again. Others even wanted to convert the two sisters into revolutionary diesel-driven ships, but none of these plans ever came into fruition. Instead the two liners remained laid up where they were.

What followed was a long and uneventful time in limbo. The two liners lay side by side in the Patuxent River, and no work could be found for them. During this time, the Agamemnon was renamed Monticello. It was not until 1940 that they once again became the matters of discussion. By now the Second World War was raging in Europe, and the two former German express-liners were offered to Great Britain for use as troop transports. Troopships were indeed badly needed, but due to their old age and the expensive amounts that it would take to make them seaworthy, the British declined. With this last possible use out of the picture, there was only one thing left to do.

That same year, the former Kaiser Wilhelm II and Kronprinzessin Cecilie were sold to the Boston Iron & Metal Co. of Baltimore for scrapping. Their last voyage was to be towed to Baltimore, where they were subsequently broken up.

Specifications

- 707 feet (215.9 m) long

- 72 feet (22 m) wide

- 19,361 gross tons

- Steam quadruple-expansion engines turning two propellers

- 23 knot service speed

- Passenger capacity of 1,888 people