1952 – 2000

Also known as Stefan Batory and Stefan

After the Second World War, many nations were faced with virtual bankruptcy. The shipping industry had suffered greatly in the conflict, with thousands of merchant ships from both sides sunk by bombs, torpedoes or mines. When the war was finally over, the difficult task of rebuilding the financial situation was imminent. For this, new ships were needed, but in many cases there were simply no funds, labour or material to build them. It would take a few years before the shipping lines had healed their wounds to some extent.

The Netherlands, however, was somewhat of an exception. The pride of the nation’s merchant fleet, the Nederlandsch-Americaansche Stoomvart-Maatschappij, abbreviated NASM and commonly known as the Holland America Line (HAL), was back in service on the North Atlantic as early as June 1946 when the new passenger-cargo liner Westerdam’s maiden voyage became the company’s first postwar passenger sailing from Rotterdam to New York. Westerdam had quite a remarkable history already, and she was something of a symbol of Holland’s survival of World War II. Laid down in September 1939, her construction had been stopped with the outbreak of war. For six years, the unfinished ship went through delays, interferences, sabotage and was even sunk three times! But in spite of all this, she survived.

Having inaugurated the company’s postwar passenger service, Westerdam was soon followed by her older sister Noordam and the larger Veendam, which had both survived wartime duties. Then, in October 1947, Holland America Line’s pride Nieuw Amsterdam made her comeback, signalling that the company was back in the game.

As the world approached the 1950s, the demand for Tourist berths on passenger liners reached unprecedented heights. In fact, the market was booming to the extent that some lines needed new ships to meet the high demand. Holland America Line was one of these companies. The so-called combi-liners, i.e. the passenger-cargo liners like Noordam class, had earlier been used for Tourist berths. But now, the demand had reached such heights that this type of ships were no longer able to keep up. As a result, HAL decided to change their plans for new tonnage.

In 1950, the cargo liner Diemerdyk had entered service, with two projected sisters to follow in her wake. However, with the current situation in mind, the plans for the two new ships were revised completely. Construction had already begun on the first of these ships in the Schiedam yards of Wilton-Fijenoord, with the planned name Dinteldyk. This was in accordance with HAL nomenclature, where cargo and passenger ships had -dyk and -dam suffixes respectively. Now, the company board instead announced that these two ships would be built as passenger liners, with the emphasis placed on Tourist class. Dinteldyk was renamed Ryndam on the stocks, and was subsequently launched as such on December 19th 1950.

On that very same date, the keel of the second ship was laid down as yard no 733.As her construction had not yet been started on when the decision was made to cancel the cargo ship plans, she was thus built from the start as a sister to Ryndam. While construction continued on her sister, Ryndam received much attention because of her revolutionary design – a design that would also be found on the ship in progress.

On April 5th 1952, the day of launch had finally arrived. Christened Maasdam by Mrs. Adriaan Gips, the new ship was the fourth HAL vessel in history to be given that name. But she was not completed yet, as she still had her fitting-out in front of her. This, however, went along at a rapid pace and after having gone through her sea trials satisfactory, the ship was officially handed over to the company on August 10th 1952, which was ahead of schedule. Subsequently, her maiden voyage, which had been scheduled for September 24th, was pushed back by a little more than one month. And so, on August 11th, Maasdam slipped her moorings and left Rotterdam for the first time. Her final destination was New York, with calls at Le Havre and Southampton along the way. This premiere sailing was a bit special though, as it also included a call at Montreal, which was arranged in recognition of ‘the ever-closening ties between Canada and the Netherlands’. On August 27th, Maasdam arrived at New York where she was greeted as the last of three new ships in 1952, the other two being the United States and the French Line’s Flandre.

As with the Ryndam a year earlier, Maasdam gained much attention because of her revolutionary design. Except for some differences in décor, the two sisters were virtually identical. For the first time on the North Atlantic run, the ships had been designed almost exclusively for Tourist Class business. There was a First Class, but this had only 39 berths, and was mainly incorporated in order to comply with the two-class requirement of the trans-Atlantic Passenger Steamship Conference. First Class was secluded on Boat Deck, while the rest of the ship was devoted to Tourist Class. There was no doubt for whom these ships had been designed, and the budget travellers were given plenty of space on these new liners. 63% of the cabins were two-berth, and although they were mainly inside cabins without sea view and only a washbasin, they were all completely air-conditioned and public facilities were ample and conveniently placed. Furthermore, there was a large number of public areas to choose from; the large Palm Court forward, a library, a card room and the Smoking Room, which was located aft. Both ships were also equipped with an outdoor swimming pool aft on the Promenade Deck, since they were also intended for cruising in the winter season.

Outwardly, there were a few ‘firsts’ as well. Ryndam and Maasdam were the first passenger ships to sport the new Holland America livery, namely a dove grey hull with a yellow band. The buff, green and white funnel colours introduced back in 1898 were retained, but the funnel design was a new one. Although they had initially been designed with a conventional funnel like that of the Noordam, Ryndam and Maasdam were ultimately fitted with a Strombos Aerofoil funnel, which had been introduced on the French liner President de Cazalet in 1950. This type of funnel was very thin, which resulted in reduced wind resistance and created a slipstream that conveniently carried away the smoke. In all, the two ships might have appeared a bit stocky, with their large superstructure placed on hulls of freighter dimensions. In addition to this, Ryndam and Maasdam were certainly not very fast ships. Their freighter engines (two cross-compound General Electric steam turbines built in 1945) gave them a service speed of only 16.5 knots. This resulted in a crossing time of eight days from Britain to New York, but on the other hand it meant a daily fuel consumption of just 53 tons.

However, this seemed to matter very little when attracting passengers. Marketed as ‘The Economy Twins’, Ryndam and Maasdam became highly popular vessels. During her first year in service, Maasdam achieved an average load factor of 85% on crossings and 96% on cruises, on which the two classes were merged into a single one. Thanks to their low running costs, the two sisters could offer passages at very affordable costs. Indeed, other shipping companies would soon adopt the economy concept, for instance Cunard who later introduced their Saxonia class in 1954.

But while Maasdam had quickly become a popular ship among the travelling public, it did not take long before she suffered her first taste of misfortune. On December 10th, after only a few months of service, she was outbound in fog from Rotterdam when she collided with the small German tanker Ellen in the Nieuw Waterweg, which links Rotterdam with the Hook of Holland. The 286-ton Ellen was sunk, and six of her crew members were tragically lost in the accident. Maasdam, on the other hand, was undamaged. A little less than two years later, on October 3rd 1954, she was outbound from New York when she hit the Transport Océaniques freighter Tofevo in heavy fog off Rhode Island. This time she did not escape unscathed, as her stem was crumpled and both ships were forced back to New York for repairs. While these were carried out, HAL faced more problems when they refused to pay for the passengers’ hotel and meal costs. Some 200 angered passengers organised a sit-down strike, and ultimately won their case. On October 27th, Maasdam returned to service.

By the mid-fifties, Ryndam and Maasdam were well established on the North Atlantic run. However, their short hulls and large superstructures could sometimes cause them to pitch heavily, and the company soon decided to try and remedy this flaw. In 1954, a new fin-like device designed by the Royal Dutch Navy was fitted on the Ryndam, but when this only turned out to make matters worse, it was soon removed. Instead, when Maasdam went through her overhaul in 1955, she became the first Holland America ship to be fitted with Denny Brown stabilisers. These greatly improved her seagoing quality, and thus the Ryndam received the following treatment the following year.

Maasdam continued her regular service into the 1960s, but by now the Tourist Class had evolved into requiring a bit more comfort than she could offer. So, in 1961 had a number of cabins amidships rebuilt to include private facilities, resulting in a slightly decreased Tourist Class capacity. At the same time, the First Class Lounge was extended, now including a special ‘Gents’ Corner’ Bar.

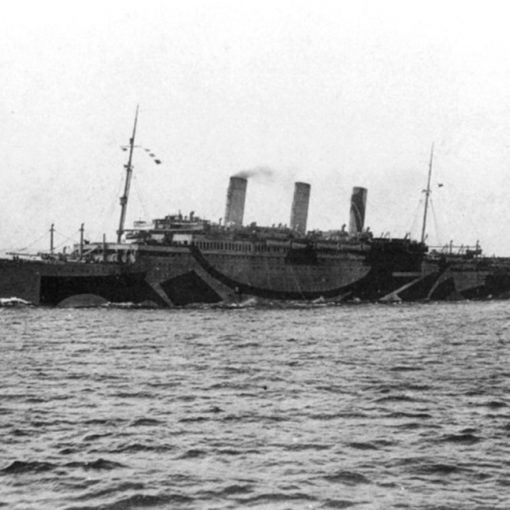

A further two years later, in 1963, Holland America Line extended Maasdam’s service to include the German port of Bremerhaven. Her first call there on February 15th could have gone better, though. While inbound in dense fog just off the Weser Lightship, shifting ice flows had displaced the channel buoys, and the ship struck the wreck of the British freighter Harborough. Maasdam was badly holed, and she quickly took on a twelve-degree list. As a precaution, the 500 passengers were ordered into the lifeboats, and were later picked up by the Weser pilot steamer. No passengers had been injured in the accident, but Maasdam herself had to be shepherded to the Norddeutscher Lloyd shipyard to undergo repairs. Missing two voyages, Maasdam was back in service on April 16th. By the end of the year, her final crossing that season also received much attention when on December 22nd an ice-covered Maasdam docked at New York two days behind schedule. During the crossing, she had battled 35-foot seas, snow, ice and sleet driven by 75 mph winds. Still, her 200 passengers and 18,000 sacks of mail had reached their destination in time before Christmas.

Overall, the 1960s brought many changes for the Maasdam and her sister. By the middle of that decade, aeroplane traffic had taken most of the passengers away from the North Atlantic liners. Ryndam had already set on an experimental round-the-world cruise in January 1965, and in October the same year Maasdam left Rotterdam on a similar voyage, calling at ports such as Freemantle, Wellington, Los Angeles, Acapulco, Kingston and New York. Then, in 1966, Ryndam was transferred to HAL’s German subsidiary Europa-Canada Line and employed doing student voyages from Bremerhaven to New York. She was thus taken off HAL’s Canadian run on which she had been sailing for a few years, and Maasdam was called in to fill that gap. Having occasionally ‘filled in’ on the Rotterdam-Quebec-Montreal run before, Maasdam was certainly no stranger to the Canadian waters. However, the ship’s relationship with the Holland America Line was nearing its conclusion. In January 1967, she set out on what was going to be her last round-the-world cruise, which terminated on April 3rd 1968. During the following summer season, she managed to average an 85% load factor on the Canadian run, much because of the fact that Cunard by now had withdrawn and Canadian Pacific had only two Empresses left in service. Nevertheless, in May 1968 it was surprisingly announced that Maasdam had been sold to Polish Ocean Lines (POL) for ‘better than book value’, with delivery to take place at the end of the season. And so, the ship left Montreal on her last HAL sailing on September 20th, and was paid off at Rotterdam on the 29th.

With that, a new chapter in Maasdam’s career began. Polish Ocean Lines was one of the Eastern bloc companies that were actually expanding on the North Atlantic. They had had plans of building a new ship for their service, but due to the financial and political situation they had to make do with used tonnage. Their choice had fallen on Maasdam, which was now being prepared to replace the ageing Batory, which had entered service back in 1936. On October 8th 1968, Maasdam was officially handed over to the Polish Ocean Lines and renamed Stefan Batory, in honour of her predecessor.

Taken in at the Gdanksa Stocznie Remontowa yard at Gdynia, Stefan Batory was to go through an extensive refit. When she re-emerged that following April, much changes had been made to her appearance. The Strombos funnel had been replaced with a streamlined one, and a new mast had been fitted above the modernised bridge. The old cargo masts had been replaced with electric cranes, and naturally she had also been painted in Polish Ocean Lines’ colours. Internally, her public rooms had been renovated, for instance turning the old Palm Court into the new Grand Lounge. Down below, the engines, boilers and electrical equipment had been carefully overhauled.

As a virtually re-born vessel, Stefan Batory left Gdynia on April 11th 1969 bound for Montreal, and calling at Copenhagen, Tilbury and Quebec on the way. During her first season, the ship averaged an impressive 93% load factor over nine voyages, much because of the great number of Polish descendants living in USA and the fact that there was not yet any direct air service between the two countries. However, Stefan Batory quickly gained a loyal non-polish following, much thanks to the good reputation of her predecessor Batory.

Following her successful premiere season for POL, the Stefan Batory was taken in to further upgrade her interiors. Much of her furnishing was replaced, and a 280-seat cinema was constructed in the forward cargo hold. With these alterations completed, the Polish Ocean Lines’ flagship could return to North Atlantic service once again.

There she stayed on, and prospered while other ships were not as fortunate. In 1971, Canadian Pacific’s Empress of Canada was withdrawn from service leaving the Soviet liner Alexandr Pushkin as Stefan Batory’s sole contender on the Canadian run. The Soviet ship was larger and faster, but did not enjoy the same popularity as the Polish flagship. This was not least evident when comparing their load factors; 92% on the Stefan Batory, compared to a mere 49% on the Soviet liner.

Continuing her successful North Atlantic service, Stefan Batory soon also became revered for her off-season cruises. In 1980 the Alexandr Pushkin was withdrawn, leaving the Polish liner as the only ship on the Canadian run. In addition, she and Cunard’s Queen Elizabeth 2 were the only two liners left in North Atlantic passenger service. It was quite a contrast to the booming years only a few decades earlier.

But by the 1980s, things started to look bleak for the veteran liner. New restrictions caused a serious decline in Polish passenger numbers, but in spite of this it was announced in 1982 that POL was planning to build a new replacement for the Stefan Batory, due to arrive in 1986. But the company was soon faced with the harsh reality, and these plans were abandoned. Instead, Stefan Batory continued her service for the company.

By 1985, the ship had made 131 Atlantic sailings and 136 cruises. After 33 years in service she sailed on, and in 1987 she became the last steam powered Atlantic liner when QE2 was refitted with diesel engines. But, that very same year it was announced that the Stefan Batory would be taken out of service in March 1988, with no ship replacing her. Stefan Batory’s service with the Polish Ocean Lines ended with a series of cruises to South America and the West Indies. She was then sold to Hellenic Polish Shipping & Trading Enterprises, Panama, retained her name and was probably intended for further cruising. However, the ship was instead laid up in Flushing Roads on June 26th, and left for Piraeus on November 1st.

There she remained, until she was again sold in 1989, this time to Erne Compagnia Maritima SA, Panama. However, they did not invest much money or interest in the ship, and by 1990 her owners were listed as the Stena subsidiary City Shipping International Inc. of Nassau. The ship was now renamed Stefan, her funnel was painted yellow and she was brought to the Swedish port of Göteborg and put to use as an accommodation ship.

In the summer of 1991, the old liner once again found herself standing in the spotlights for a brief time when an Italian-French company used her for a production, in which she was given the script name Las Delicias. In August that summer, following her short stint as an actress, the ship was once again towed to Piraeus, this time to undergo a conversion into a modern cruise liner.

But, once again fate intervened. The ambitions conversion plans were soon shelved, and not much happened to the old vessel. Spending nearly eight years in lay-up at Chalkis in Greece, the Stefan was finally sold for demolition in 2000. On March 22nd that year, she arrived at the beach of Aliaga in Turkey, and the local shipbreakers started the task of cutting her up. Before the year was over, the former Maasdam had been completely dismantled. With that, a career that had lasted for nearly half a century came to a definite end.

Specifications

- 502 feet (153.4 m) long

- 69.2 feet (21.1 m) wide

- 15,024 gross tons

- Geared steam turbines turning a single propeller

- 16.5 knot service speed

- Passenger capacity of 881 people

10 thoughts on “Maasdam (IV)”

My father (Aart) sailed on the SS Maasdam from the 50’s to 1965, he was bosun and sailed with first officer Anton Gosling who generously gave me a tour of the ship and watched a movie with me in the cinema. I was 14 when our family sailed on her from Rotterdam to Australia and my father retired from the sea. I felt delighted that so much of the ship was available for me to visit. I was treated with great kindness and humour by the ‘bemanning’ and officers alike. I remember I won a twist competition in the Palm Court, but was too shy to dance by myself when asked. The reason given was that my father had always been away at sea for my performances. The band was happy to play any music I would need to put on a little show, oh the pressure! The offer was clearly made to express affection and cameraderie to my father, and allow him to see me perform just once. It was a warm and collegiate atmosphere and times have changed. The seamen of all ranks, manning the ship or serving the passengers showed warmth and cameraderie, it was a wonderful experience.

My family emigrated from Holland to the US on this ship in 1953, arriving in Hoboken. It was October, the seas were rough, and I spent most of the voyage being seasick. The last day waters were calm and we saw SS United States outbound and the Statue of Liberty as we entered the harbor.

My family sailed from NYC to Rotterdam on the Maasdam in 1963, and returned 6 months later on the Rotterdam. Some wonderful childhood memories. I remember hearing about the collision mentioned in this article, on its very next voyage after ours.

My father came to Canada aboard this ship in 1956, emigrating from the Nederlands. He always spoke fondly of his crossing and mentioned it had a party like atmosphere.

I sailed on the Maasdam on one of its last voyages, from Montreal to L’Havre in mid July 1968, right after I graduated high school that June. For this voyage, the ship was filled with student charter groups, about 800 or so people.

It took well over a week since we arrived in L’Havre towards the end of July. It was a very animated atmosophere, students from all over the U.S.A. and Canada meeting and getting to know each other. My charter group was called “Travel Study International.”

There was a lot of seasickness felt by people throughout the voyage, but if you stayed in the middle of the ship it was easier to deal with. Food was “institutional cooking”, jokes were made about the Ox-Tongue served one evening at dinner. The palm court was always populated, and the last couple of nights there was a DJ playing rock music that was popular at the time. I shared a smallish cabin amidships with two other fellows, very much like the ones described in the text. We had maybe two lifeboat drills during the trip. We left Montreal and went up the St. Lawrence seaway, passing

Quebec. We did not get out into the middle of the Atlantic Ocean until about the the third day.

Being on the Maasdam IV was a unique and special experience for me, an eighteen year old at the time, between high school and college.

All went well, it was great crossing the ocean for the first time. I would gladly love to do it once again, and I’m sure if it were on a Holland-America line ship, everything would be of exceptional quality.

We sailed on the Maasdam in August 1966. I’d be grateful if anyone can tell me where we boarded. I had a memory that we were brought out to the ship in Galway, but maybe it was Cobh. We landed in New York about six days later, I believe. I’d love to get details of that trip confirmed, find the passenger manifest, etc.

I crossed the Atlantic on the Maasdam in December, 1963. The ship developed a major list several days out which lasted most of the rest of the voyage; and then we hit a gigantic storm with hurricane force winds, finally coming in to NY harbor covered in ice inches thick. Would love to connect with anyone else from that passage,

Sealt on the maasdam in february 1967 from Rotterdam to Halfax it was a rough ride aldeway.

My wife and I sailed on the Maasdam from Montréal to Le Havre on 24 June 1968. The sailing was a bit rough because there was a storm in the North Atlantic and we got the tail of it. We were late arriving at Le Havre because of that. We have found memories of our sailing. We came back the following year on the Alexander Pushkin. That sailing was not as enjoyable as the one on the Maasdam because the atmosphere was very sovietic.

Thank you for sharing your memories of crossing the Atlantic on the Maasdam! I am curious to know about the ‘sovietic’ atmosphere on the Alexandr Pushkin; could you elaborate on this, please?