1911 – 1935

In 1897, the Germans had struck the British a major blow concerning shipbuilding. The swift, new Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse would be the first of a spectacular quartet of ships that would soon conquer the North Atlantic. With a service speed in the vicinity of 22.5 knots, the Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse snatched the Blue Riband right out of British Cunard Line’s Lucania’s hands. This was a terrible shock for any Briton and especially for Cunard, who had totally been left behind in the battle of the Atlantic. In 1901, the White Star Line could still boast their 21,000-tonner Celtic to be the largest ship in the world, but Cunard’s best bid was far away from its competitors both regarding speed and size. There had to be a beat back once again – and this time from Cunard.

There was one problem though. Cunard was not in the best of times, and their financial situation did not allow them to build a serious competitor either to the fast Germans or the large White Star Line. They had to turn to the British Government for a massive loan in order to build not one, but two enormous liners that would outmatch both the Germans and the White Star Line. Of course, the Government was eager to surpass the Germans, but they needed some sort of security from Cunard before they agreed. The ’security’ was that both liners should be able to be quickly transformed into military cruisers in the event of war. The two liners would ultimately become the famous Lusitania and Mauretania, who took both the distinctions of being fastest and largest in the world. The Germans, and especially the White Star Line had been left out of the race.

In 1901, White Star had joined the ever-expanding American company IMM with Junius Pierpont Morgan as chairman. Morgan’s intention was to create a monopoly on the North Atlantic, and his next goal after the White Star Line was Cunard. However, Cunard and the British Government had prevented this when they independently started to build the Lusitania and the Mauretania. Naturally, White Star wanted to outdo their rivals, and they did not have to do it with the Government’s help. With the IMM’s help, a possible outmatching of Cunard was in the sight of White Star.

Ever since the White Star Line had built their first Oceanic in 1871, they had constructed their vessels at the Belfast based shipyard Harland & Wolff. They had an agreement that White Star was to build all their ships at the shipyard provided that Harland & Wolff did not construct any ship for a competing shipping company.

In 1908, the chairman of Harland & Wolff, Lord Pirrie and the chairman of White Star, Bruce Ismay, had dinner together one night at Lord Pirrie’s Belgravia mansion. During this very night plans were made about how to outmatch Lusitania and Mauretania. Firstly, Pirrie and Ismay visioned two great liners with three funnels that would beat Cunard’s ships both in speed and in size. However time would show different. As plans became more and more serious, a picture of the new set of ships became clear.

The pair of liners had been turned into a trio. The trio of funnels had been replaced by a quartet to create symmetry, and to reassure emigrants that the ship was big and safe enough. All three would have a tonnage that would leave Mauretania some 15,000 tons behind. This meant that the new White Star ships would become monstrous in size. But at 45,000 tons, it would be too uneconomical to drive the ships at the required service speed around 26-27 knots that was needed to gain the Blue Riband. The spectacular about these three liners would be their size and their luxury.

At first, the main feature on board the new ships would be a spectacular first class dining room that went through three decks. After some time this was altered though, and instead, the first class entrance stairway would have the honours. Another special feature would be the third class accommodation, which would become high above other liners’ standard, even in the future.

One of the problems that remained was what sort of engines the new ships would have. Conservatives within White Star opted for the traditional twin screw that had proved reliable on the popular Celtic-class, while others suggested a whole new type of engines that consisted of the traditional triple expansion engines that drove two wing propellers and a turbine engine – powered by the triple expansion engine’s exhaust steam – driving a centre screw. The White Star Line was so unsure in this question that they purchased two liners from the Dominion Line. The first of them – Megantic – was driven by the traditional twin screw, while the second – Laurentic – was equipped with the new engine type. The two ships were close to identical at 15,000 gross tons and after some time in service in 1909, the Laurentic proved to be both faster and more economical. The machinery for White Star Line’s new giants had been selected.

Unlike Cunard and other shipping companies, White Star did not keep the names of their new vessels a secret until the launch approached. As soon as construction began on 16 December 1908, onlookers could see on a sign on the gantry, that the new ship being constructed at Harland & Wolff’s slip number 2 was the Olympic.

Actually, the gantries for the new ships had originally been three different slips called No. 1, No. 2, and No.3. But the massive size of the Olympic-class required larger gantries, and so these three slips were transformed into two – one for the first of the class, and one for the second. The third ship would follow only if the first two proved successful, and would in that case be constructed on the Olympic’s slip. During the fist months of the Olympic’s construction, work on gantry No. 3 was still progressing.

The hull of the Olympic would be over 880 feet, containing 16 watertight compartments. Eight of these would be used by the propeller shafts, and the 29 boilers extended themselves over 320 feet. The giant expansion engines stood four decks high and are actually the largest engines of this type ever to be constructed. These engines, together with the turbine created some 50,000 horsepower, in order to drive the ship at its predicted service speed of 21 knots.

After the keel of the Olympic had been laid, the framing of the ship started and this was finished on 20 November 1909. What followed was to rivet the hull plates in place, a task that was not completed until April 1910. The predicted launch date in the autumn the same year seemed manageable to maintain. Still, one problem remained. In both Southampton and New York the port facility management was not eager to upgrade their ports in order to receive the Olympic-class. They thought it reasonable for White Star to pay the upgrade for themselves. The White Star Line and IMM had to keep on pushing until the ports finally faced the logical and agreed to pay the price. By the autumn of 1910, the hull of the Olympic had been plated and painted – everything was ready for launching. The hull was painted in a light grey colour so every line of the ship would be at its best on the photographs that would be taken by the press during the ceremony.

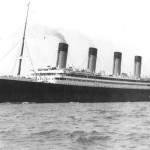

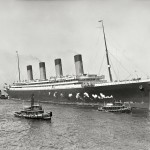

On Thursday 20 October, 1910 at 11.00 am, in the presence of Bruce Ismay, Lord Pirrie, the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, the Lord Mayor of Belfast and a huge crowd, the Olympic was ready to leave her slip. Both the British and the American flag were hoisted and flags at the stern spelled out the word ’Success’. Roughly 23 tons of tallow, train oil and soft soap had been spread on the slipway to make the ship’s descending easier. After a quick ’ceremony’ excluding bottles of champagne crushed against the bows, the 20,600-ton hull of the future Olympic entered the water with its full length in 62 seconds reaching a maximum speed of 12.5 knots. By now the fitting out could commence.

Prior to the construction of the Olympic, a huge floating crane had been ordered by Harland & Wolff. This 200-ton creation came into much use, due to its great lifting capacity. While work on building the upper decks was underway, the floating crane lifted all the 29 boilers in place through the openings where the immense 60 feet/25 metre funnels would later be placed by the same crane. On April 1, 1911 the Olympic was dry-docked in the newly completed Thompson graving dock, a dock specially constructed by the Belfast Harbour Commissioners in order to accommodate the new Olympic-class. Here, the vessel would have her propellers fitted and here she would be converted from the hollow shell she still was to the great luxury liner she would become.

Alongside with the construction of the Olympic and the Titanic, White Star had ordered two new tenders from Harland & Wolff to operate in the French port of Cherbourg where the Olympic-class ships were too large to dock for themselves. These two new vessels were the only ones in the world that were large enough to handle such large ships as the Olympic and the Titanic. They were called Nomadic and Traffic. Nomadic took care of all the first and second class passengers on their way from the harbour to the ship, while Traffic saw to the third class. When the Olympic was finished fitting out on May 29, and ready for her sea trials, the Nomadic and the Traffic escorted the new flagship of the White Star Line into Belfast Lough.

On the same day the Olympic started to undergo the sea trials. She had taken on 3,000 tons of best Welsh coal, and 250 runners had been sent from Liverpool to help navigating the huge liner. The day before, the Mersey tugs Wallasey, Alexandra, Hornby, Herculaneum and Hercules had swinged the Olympic, and now the vessel was adjusting her compasses just prior to the actual engine tests. In all, these took two days, and the expectations were well exceeded. The fact was that the Olympic was able to maintain a speed well above her designed 21-knot service speed. The very same day as the last day of sea trials for the Olympic was the Titanic’s launch. The large guest party came directly on invitation from the White Star Line from the launch to the finished Olympic to view the new pride of Britain. Arriving on the specially chartered cross channel steamer Duke of Argyll, the guests got the first glimpse of how beautiful the new White Star trio would be. Among them were for instance J.P. Morgan who had travelled all the way from London to witness the launch of the Titanic and the finished Olympic.

As customary when a White Star ship had been finished, the Olympic now sailed for Liverpool for public inspection. Even though the main port of call in Britain had been changed from Liverpool to Southampton in 1907, you could still read Olympic –Liverpool under the ship’s stern, and White Star headquarters remained on 30 James Street in the city.

One of the things the approaching Olympic-trio was known for was their extreme safety. Just as with cars today, shipping companies invested lots of money in having the safest ships afloat. The Cunard Line’s Lusitania and Mauretania had double bottoms and double sides to prevent a fatal damage. Just like the Celtic-class, the Lusitania and Mauretania were known to be unsinkable. This word, ’unsinkable’, was used once more concerning the Olympic and Titanic by the quarterly published British magazine ’The Shipbuilder’ and from then on the Olympic and the Titanic were considered ’unsinkable. ’…in the event of accident, or at any time when it may be considered advisable, the captain can, by simply moving an electric switch, instantly close the doors throughout and make the vessel practically unsinkable.’ These doors were watertight hatches for the openings in the sixteen watertight compartments that divided the ship, and were installed to ease movement along the bottom of the ship. Ant two of these compartments could be holed at the same time without endangering the safety of the ship. At the bow – which is the most likely area of a collision – up to four compartments could be filled with water simultaneously. A damage beyond that was rather soberly looked upon as unrealistic.

On June 1, the Olympic left Liverpool for Southampton, which would be her starting point on her maiden voyage. In this port, she was visited by some thousands of people, who just as the Liverpool-people witnessed something of the most beautiful ever created by any human. The inside of the Olympic was simply exquisite. The large public rooms outdid any other creation on the sea. Not being as breathtaking as German ornament orgies, the style was more discrete and perhaps therefore more appealing. As mentioned, the dining room was made in one deck only but it was still the largest room in the world ever to go to sea. The room was done in Jacobean style, could accommodate 532 people per sitting and stretched the full width of the ship. Another splendid feature was the first class smoking room. It was done with dark fittings and cosy armchairs with adjacent green playing tables. Special features were also the grand reception room on D-deck, adjacent to the dining room and the already mentioned forward grand stairway. Passengers – first class only of course – could also enjoy some time in the lounge or in the spectacular Turkish bath available. To make things even more comfortable, running around was not required in order to use all these facilities, because just behind the magnificent forward Grand Staircase three lifts were available. For the even more enthusiastic passenger, a gymnasium was available on the boat deck with different fitness tools such as a rowing machine or electrical camels. Added to all this, the first class passenger could have his cabin in a wide variety of styles – Jacobean, Georgian, Dutch, Louis XIV, Empire and many more. The main first class promenade areas were situated on the boat deck, on A-deck and on B-deck.

There was also very good standard in the other classes on board the Olympic compared to most other liners. The second class was often referred to as ’like any first class standard on other ships’. The dining room was made in a fairly decorated Early English style and could have roughly 400 people seated at one sitting. The smoking room was also done in a distinguished British style with plenty of dark wood panelling. The staterooms were also of a very selected sort. If you as a second class passenger wanted to take a stroll on deck, the boat deck that was shared between the first and the second class was the main attraction.

Third class – or steerage – was high above earlier North Atlantic standard. In pre-1900 ships, it was not uncommon that all third class passengers slept in one big dormitory, rather than in private staterooms as on the Olympic. True, there was a dormitory, but only for a small percentage of the passengers. If you travelled in third class, you were able to reside in a two-berth cabin, but usual procedure was to share with three or more fellow passengers. The amusement facilities were somewhat limited, though. The men had access to a quite large smoking room situated below the poop deck. Wall to wall in an identical room was the ’Third Class General Room’, where the passengers could gather to enjoy themselves in all the spare time they all of a sudden had when at sea as passengers. Forward on D-deck, there was an open space where passengers also could enjoy themselves, and here, a piano was placed by White Star for the passengers to use and enjoy. The open promenade areas were situated on the two well decks and on the poop deck and forecastle. It was quite clear that no passenger would suffer from discomfort!

After the Olympic had berthed at Southampton on June 3 and she had received an official welcome by the mayor, loads and yet again loads of porcelain, cutlery, linen and provisions were embarked on the great liner. Last minute fitting out was completed by Harland & Wolff staff as the date of departure drew nearer. The day for the maiden voyage had been scheduled to June 14, but that did not seem to work out for the White Star Line as the workforce responsible for coaling the ship suddenly went on strike. Eager to remain on schedule, White Star employed a large force of Yorkshire miners to fulfil the task.

At midday on June 14, the booked-solid Olympic cast off her moorings and reversed out of the Ocean Dock into the River Test before she sailed for Cherbourg, Queenstown and finally New York. Her captain was Edward John Smith, the oldest and most trusted of the White Star Line masters. Bruce Ismay was also on board and spent his time on checking things that could be bettered. He noticed that there were no cigar holders in the first class bathrooms and, more seriously, he realised that the first class promenade on B-deck was not used enough and he suggested that the area would be deleted on the Titanic, that was still being fitted out at Belfast, in favour of extended first class cabins. Added to this, the open promenade area on A-deck was badly affected by spray from the water, and yet another suggestion from Ismay said that the forward part of this area should be glassed in on the Titanic, and perhaps later on the Olympic. When the Olympic berthed at her Pier 59 in New York, she had averaged a flawless 21.7 knots for the entire crossing despite some rough conditions during the voyage, which was not bad for a 21-knot ship! Ismay telegraphed immediately back to Pirrie at Belfast saying: ’Olympic is a marvel, and has given unbounded satisfaction’.

The first taste of bad luck for the Olympic-class occurred when still at New York – the 200-ton tug O.L. Hallenbeck was sucked towards the Olympic resulting in a badly damaged stern frame of the smaller vessel. The 45,000-tonner emerged almost unscathed except for some scratches in the paint. On June 28, the Olympic was ready for her return voyage to Southampton. When the ship was just outside New York, one of the passengers realised he had forgotten his glasses on shore. The Olympic telegraphed to New York, who transferred the message to the spectacle manufacturer. Within short, they had replacements ready and all packed up they were loaded on board a small aircraft, which flew out to the still steaming Olympic. When the plane came in above the Olympic, the pilot dropped the parcel onto the decks of the huge ship below. This would all have been a fantastic story if it were not for the fact that the parcel hit the very edge of the Olympic, and sadly bounced off into the ocean never to be recovered. But as the Olympic could boast to have made her first eastbound crossing with an average speed of 22.5 knots, there was still a happy ending.

The first to- and fro-crossing of the Olympic had gone off fabulously, and now she slowly began to settle in what would become a very distinguished career. She would be the largest ship in the world for another year before the Titanic entered service with a slightly larger gross tonnage.

On September 20, the Olympic steamed out of the Ocean Dock for the fifth time on what was thought to be yet another normal crossing to New York. The master was still E. J. Smith, and the chief officer was another well-known man – Henry Wilde. As Olympic had passed through Southampton Water she had to do the usual reverse S-movement before she could sail east past the Isle of Wight’s Northeast coast. At the same time the British battle cruiser HMS Hawke was off Egypt Point at the north coast of Isle of Wight. She too intended to steam eastbound on approximately the same course as the Olympic. As the Olympic almost had completed the mirror-S, the Hawke came in alongside the Olympic on a parallel course. What then happened is still somewhat a matter of debate. The huge 45,000-tonner seemed to pull the smaller 7,350-ton Hawke towards her with such power that the warship had no chance to steer away. At first, Captain Smith though that the Hawke tried to turn in under his overhanging counter stern, but a collision at this point now seemed inevitable. Seconds before the collision, Captain Smith told his pilot, George Bowyer: ’I don’t believe she will get under our stern, Bowyer.’ Bowyer replied: ’If she is going to strike, sir, let me know so I can put the helm hard over to port.’ Is she going to strike, sir?’ Captain Smith’s answer told him the truth: ’Yes, she is going to strike us in the stern.’

The Olympic tried to swing her stern away from the approaching vessel, but the action was too late. In chaos of sparks, the Hawke’s bow plunged into the hull of the Olympic, just below her main mast. The cruiser narrowly avoided capsizing, but her master, Commander Blunt, managed to close all the watertight doors in time, and after a large section of the Hawke’s bow had fallen off, he had collision mats put over the front side to prevent an uncontrolled entering of seawater. The Olympic had also suffered considerable damage. A triangular hole just between two large watertight compartments stretched from below the waterline up to D-deck. Captain Smith immediately ordered all the watertight doors closed. Two of the largest watertight compartments was rapidly filling with water, but Smith knew that his ship would not sink in spite of this serious damage – any two compartments could be opened to the sea without mortally wound the Olympic. However, Captains Smith’s ship was no longer able to complete the voyage, and she could not return to Southampton owing to the tide. She had to unload all her 1,300 passengers on tenders that brought them to shore. Nine of the passengers managed to get to Liverpool in time to get on the New York-bound Adriatic the next day, but the rest had to push their schedules a bit.

When the tide permitted the Olympic to enter on the 21st, she went back to Southampton to be patched with wood so she would be able to carry through the required voyage to Belfast for more thorough reparations. On October 3, the Southampton work was completed and Olympic left for Belfast, at a very reduced speed of ten knots, in which she arrived on the sixth. The White Star Line was so eager to get the Olympic back in service that they delayed the Titanic’s maiden voyage, concentrating all possible Harland & Wolff-workforce on the stricken Olympic. On November 20, the Olympic was ready to enter service again.

But who was responsible for the accident? Both parts had clean consciences, the Olympic blaming the Hawke of being too close and, of course, vice versa. Two days after the collision, an Admiralty court of enquiry freed Commander Blunt of blame, blaming the Olympic of crowding out the Hawke, and by overtaking the smaller vessel at such high speed, sucking her towards her 45,000-ton self. As late as January 1913, the White Star Line tried to clear themselves by offering to find the exact position where the collision took place. In order to prove they had not been to close to Isle of Wight, White Star would try to find the broken of bow of the Hawke. Unfortunately, Commander Blunt claimed the bow had fallen off some time after the collision, so nothing could be proved. Up until this day, the Olympic is officially to blame for the collision because of neglect.

The rotten luck seemed to continue when in February 24, 1912, she lost a propeller-blade during an eastbound crossing. Again, the Olympic had to go back to Belfast for repairs, and again, the Titanic’s maiden voyage had to be delayed. This time the maiden voyage of the latest addition to the White Star Line fleet – the largest and most luxurious ship in the world – was set to April 10th.

Just as the Olympic, the Titanic cast her moorings from the Ocean Dock, but Titanic entered Southampton Water head first. Captain E. J. Smith had been transferred to take the Titanic on her first voyage, and then he would retire. The size of the ships was once again questioned when the 10,000-ton New York was pulled towards the Titanic due to suction at the immediate start of the voyage. The near-collision was avoided when quick-minded tugboat masters quickly got hold of the New York and pulled her away to safety. The Titanic’s first voyage would become far more dramatical, as it would prove. On the night between the 14th and the 15th, the Titanic struck an iceberg 600 miles off Newfoundland, which punctuated her hull along six compartments along the starboard-side bow. In spite of all the confidence people had about the Olympic and Titanic, this was enough to sink the largest ship in the world. She settled slowly on an even keel, but due to the extreme lack in lifeboats, 1,500 people out of the 2,200 on board died in the freezing water.

On the 13th, the Olympic had departed from New York on yet another eastbound crossing. Commanding her was Captain Herbert James Haddock, who had taken over from E. J. Smith when he was transferred to the Titanic. Just after midnight, Captain Haddock received message that the Titanic was damaged after a collision. Not knowing how serious the situation was, Haddock asked the Titanic if they were coming to them, or if the Olympic should come and meet Titanic. The short reply was: ’We are putting the women in the boats’. Captain Haddock immediately replied that he would light up all possible boilers and head for his ship’s dying sister. But, unfortunately, the Olympic was too far away, and so she had to stand by as a frustrated observer. The three vessels closest to the Titanic were the Leyland liner Californian, the Mount Temple and the Cunard liner Carpathia. Both Californian and Mount Temple were trapped in massive pack ice, but Carpathia steamed quickly to the disaster scene. However, her arrival was too late, and by the time she got there, Titanic had already foundered. Carpathia was the only ship with survivors from the 20 lifeboats. The Olympic offered to unload the Carpathia somewhat, but the latter ship’s master, Captain Arthur Rostron, refused to let his passengers see the Olympic, who could be seen as a sort of ’Ghost-Titanic’, coming back from the dead. The Olympic resumed her voyage to Southampton, and when she arrived on the 21st she reached a city in mourning. It seemed that almost every family had some relatives or friends who had perished on the Titanic.

The Olympic’s next scheduled departure was on the 24th of April, but before it could commence, adequate numbers of lifeboats had to be loaded on board. Forty extra Berthon collapsibles was lowered onto the decks of the liner under the supervision of Captain Maurice Clarke from the Board of Trade. He was actually the same man that had inspected and allowed the Titanic to depart on the 10th. Shortly afterwards, it was revealed that only an additional 24 boats were actually needed. This caused a rumour saying that all 40 boats had been taken on board because they had not passed the tests properly. Unfortunately, this led to a strike amongst the crew, who left the ship saying they would not return until proper wooden lifeboats had been installed. Eager not to delay the Olympic’s departure any further, White Star mustered another crew quickly to fill in the gaps. But this time the crew that had remained on board went striking because they did not want to work with the new crew whom they regarded as ’the dregs of Portsmouth’ or inexperienced firemen. In the end White Star had to cancel the Olympic’s voyage, and after three weeks of waiting she set out on a further seven voyages, but then she was sent to Belfast on 9th October for a massive overhaul.

Where the Titanic had failed, the Olympic would now succeed. A complete set of 64 reliable, solid lifeboats was installed along the boat deck, on top of each other. The sides of the ship’s hull was torn free and an inner skin was constructed, plus that the bulkheads were raised much higher that before. This overhaul would result in several other changes as well, as for instance a copy of the popular Café Parisien on B-deck. Probably, the A-deck would have been glassed in as on the Titanic, and the B-deck first class cabins extended to the sides of the ship, devouring the rarely used promenade areas, but since the lifeboats deleted so much deck-space on the boat deck, these areas now became attractive.

Not until 22nd March 1913, the Olympic was ready to resume service again. She was advertised as the ’New Olympic’, but the Titanic-disaster was naturally never mentioned as cause for the changes. The White Star express service during the winter 1912-1913 had been upheld by the Adriatic, Oceanic and Majestic. At the time of her return, the Olympic’s gross tonnage had increased to 46,359; thereby regaining the title of being the largest ship ever built. She would not keep the title for long, though, because German HAPAG’s 52,000-tonner Imperator entered service in June the same year.

Once again, the Olympic settled back into her career. In February, her long awaited sister, the Britannic, was launched in Belfast. She would be over 48,000 gross tons, and therefore become the largest ship ever constructed for Britain until the arrival of the Queen Mary in 1936. The White Star Line already planned a replacement for the Titanic in a 33,000-tonner that would be called Germanic. Slowly, times were getting better again as White Star started to regain their reputation.

However, on August 4, 1914, Great Britain and France went to war with Germany and Austria in what would be called the First World War. At this time, the Olympic was westbound for New York and Captain Haddock ordered her to speed on in order to reach her destination as fast as possible. When in New York, Olympic was painted in a grey colour scheme – her superstructure light grey and the funnels slightly darker. Even though the greatest war in the history of mankind had erupted, White Star wanted to maintain a passenger service between Britain and America. The White Star-ships responsible for this wartime service were Olympic, Adriatic and Baltic. The first voyages were packed as the Americans trapped in Europe were eager to get back home, and British in America were keen to go back and fight for king and country.

As things seemed to worsen, the Olympic was called back from her commercial service on October 9, when she left her new European port of call at Greenock for the last time. She was ordered to be sent up to Belfast, but as German U-boats lurked in the Olympic’s path, the voyage was not to become uneventful. Unwittingly, the Olympic entered a German minefield just off Tory Islands on 27th October. At the same time parts of the British war fleet became visible as the HMS Liverpool and the brand new 23,000-tonner HMS Audacious arose by the horizon. Suddenly, the Audacious struck one of the mines and became seriously damaged. All ships except for the Liverpool – who was supposed to help evacuate the stricken vessel – were ordered to leave the area. The Olympic was also called in to help. Some two hours later, all the Audacious crew had been taken off on board the two assisting ships. The next step was to tow the Audacious to safety where repairs could be carried out. The vessel strong enough for this task was the Olympic, and after a cable had been attached between the two ships the tow started at 2.00 pm. But the sea had suddenly became rough, and the Audacious became unmanageable as her steering gear had failed. The tow cable snapped, but another attempt was made by the Liverpool. As the Audacious began to sink deeper in the water, the decision to leave her until the next day was made in order to see if she was worthwhile saving. As the Liverpool and Olympic, along with other assisting war ships, left the scene, a massive explosion occurred on the Audacious causing her to immediately sink stern first. The only casualty during the whole incident was Petty Officer William Burgess who had been standing on the decks of the Liverpool when a piece of armour plate hit him from the exploding Audacious. The same evening, the Olympic disembarked the Audacious’ crew, and continued her voyage to Belfast where she would be laid up.

In Belfast, the Olympic would meet her still fitting out sister, the Britannic. They would spend the next seven months laid up together until the Olympic was called in for Government service. The White Star Line wanted Captain Haddock to be in command again, but as he was too busy with work at Belfast, a new captain was chosen by the Admiralty and Harold Sanderson – the man who had taken over after Bruce Ismay in charge of the White Star Line. The new master was Captain Bertram Fox Hayes, the former master of the Adriatic.

Before entering the delicate oceans of the world, the Olympic was equipped with massive guns. A 12-pounder gun on the forecastle was installed, as were two 4.7″ guns on the poop deck. From now on the Olympic was referred to as Admiralty transport T2810. The first voyage the Olympic would make in this guise was to Mudros in the Mediterranean on September 24, to land some 6,000 troops for the Southern Countries Yeomanry and the Welsh Horse Division.

When off Cape Matapan on October 1, 1915, the Olympic sighted lifeboats from the sunken French steamer Provincia. Captain Hayes immediately ordered the Olympic stopped in order to pick up the survivors. After a completed work, one of the guns on board sunk the empty lifeboats. A grateful French nation offered Captain Hayes the ’Médaille de Sauvetage en Or’. However, the British were less enthusiastic. The Admiralty blamed Hayes of having seriously risked his vessel with 6,000 souls on board when stopping in extremely dangerous waters.

This sort of chivalrous war had reigned in the beginning of the war, but was almost completely deleted earlier the same year in May when the Lusitania, who was still in passenger service was sunk by a German U-boat with passengers and all. The over 100 Americans on board who had perished hurried the decision for the Americans to enter the war on the British/French side, and this in turn hurried the war towards an end.

On 21st December the same year, the Olympic was back in Liverpool after yet another successful trooping voyage. Moored at the Olympic’s adjacent pier was the newly completed Britannic who had been requested as a hospital ship for Mediterranean service. Again, White Star Line had two sister liners of top class in service at the same time. This was the second time the ships met, but also the second to last. The Britannic left Liverpool on December 23rd, while the Olympic remained where she was until she left on January 4th bound for Mudros on yet another trooping voyage. The last trip to Mudros occurred in the spring of 1916, when no great ships were needed any longer in the Mediterranean. The only hospital ship to remain in this service was Britannic.

The Olympic continued her war duties when she was called in as a troopship between Britain and Halifax, Canada. By now, the grey livery had been abandoned and Olympic received a dazzle paint camouflage scheme. During one of these voyages the Olympic had briefly encountered the Britannic at sea, but all hopes of a shared North Atlantic service after the hostilities were shattered when the Britannic was reported sunk in the Mediterranean by a German mine or torpedo.

The war raged on for another couple of years, and on April 24, 1918, the Olympic went out on her 22nd trooping voyage, this time between Southampton and New York. After a successful crossing, the Olympic returned towards Britain on May 6. When she reached British waters – which were considered a war zone – she was met by four American cruisers that were supposed to escort her during the last stage of the voyage. When in the English Channel, the ship’s lookout suddenly spotted a German U-boat U103 lying still at the surface off the Olympic’s starboard bow. Obviously, the German captain had not noticed the Olympic’s presence, but as the latter fired a shot towards the U103, he was certainly very hastingly alerted. The submarine was so close that it was impossible to depress the guns low enough to hit it, and the shot went over. The German master, Captain Rücker, saw his only chance as to dive and escape. But the U-boat was not fast enough the Olympic caught up with her and with Captain Hayes sense of perfect navigation; the full force of the 46,359-ton Olympic hit the 800-ton U-boat, and halved it. The wreckage stood on its end as the liner passed and U103 then quickly sank. The Olympic left the American USS Davis to pick up the 31 German survivors before she continued to Southampton.

The damage on the Olympic was hardly noticeable above the surface, but below you could see that the stem had been twisted eight feet to port. In spite of this, there had never been any leak. Captain Hayes was once again awarded, this time by the enthusiastic British. He received the DSC, while the two lookouts that had spotted the submarine, got the DCM and a £20 bonus.

In November 1918, the Germans had to sign the unconditional surrender at Versailles, and with this action the First World War was officially over. The Olympic completed some other voyages between Canada and Britain before she was officially handed back to the White Star Line. This happened during a minor overhaul at the Gladstone Dock, and at the same time a large 18″ dent was discovered in the hull below the waterline. Since the logbook did not reveal any sort collision with another vessel, Captain Hayes conclusion was that the Olympic had been hit by a torpedo during the war, but it had fortunately failed to go off. On August 16, 1919, the Olympic arrived back in Liverpool for a brief visit before she steamed to Harland & Wolff in order to go through an extensive refurbishment and overhaul.

During the overhaul, the Olympic changed her power source from coal to oil. Oil was more expensive than coal, but it reduced refuelling time from a few days to a few hours, and the engine room personnel were cut down from 350 to 60 people. All of the ship’s 29 boilers were removed and replaced with oil tanks. Usually, oil also improved the performance of a ship, making its engines run much more smoothly. And, of course, all the annoying coal flakes falling down in the passengers’ faces were deleted. This unfortunately also meant that the ship’s doctor almost had nothing to do, since his main job before the conversion had been to remove flakes from people’s eyes. The lifeboats were also rearranged. The capacity was still well above the maximum number of passengers the ship was allowed to carry, but now White Star put the boats inside one another, thus opening up some of the decks again.

The summary of the war was that all too many of the merchant fleets vessels had been lost. Cunard had had an astonishing 22 vessels sunk during the duration of the hostilities. To rebuild the fleets was not an easy task. Some of the most important vessels White Star had lost were Britannic, Titanic and Oceanic. There did not remain any ship to match the Olympic neither in size nor in speed. Before the war, White Star had announce plans to replace Titanic with a Germanic, but as the financial situation was at the time they could simply not afford it. But as Britain was among the victorious states at the outcome of the war, there proved to be many advantages for them. One of these was that many important foreign vessels were handed over to them. At first, White Star tried to gain HAPAG’s Imperator, but she had already been given to Cunard, becoming their Berengaria. But two other large ships of interest remained. They were the 35,000-ton Norddeutscher Lloyd liner Columbus, and the still building 56,000-ton HAPAG liner Bismarck. In spite of the time-delay it would cause to complete the vessels, White Star Line expressed their interest.

At the same time the Olympic was finished with her post-war refit and emerged with 46,439 gross tons on 17th June 1920 from Belfast. Her first commercial trans-Atlantic voyage since 1914 started on 26th June, and she reached New York after a successful crossing on July 2. Once again, the Olympic settled back into what she was built for – a successful passenger service.

During one westbound crossing in late August 1921 one of the most peculiar events in the Olympic’s career occurred when a Thomas Brassington left a letter in his cabin to his fiancée Annie Thompson saying: ‘I Thomas Brassington leave all my personal belongings to Annie Louisa Thompson, 635 Haight Avenue, Alecueda, California. My troubles at home and the thought of Ellis Island are more than I can bear’. The ship was searched and finally Annie found Thomas on deck but as he threatened to jump over the side, Annie fainted and when she regained conscience, Thomas was gone. There was no success in finding him this time, and the captain wrote in the logbook that Mr. Brassington probably had committed suicide. The return voyage was to become all the merrier as British actor Charlie Chaplin had chosen the Olympic for his first return to Britain in twelve years. The comedian made great use of the Turkish Bath, the gymnasium and the swimming pool. He also spent much time in the smoking room, but only as an observer of the professional gambler’s card play.

In late 1921, Captain Hayes was appointed the post to take command of the soon-completed Bismarck, fitting out under the supervision of Harland & Wolff in Hamburg. When the 56,551-ton vessel entered service in 1922, she had been renamed Majestic. She became a worthy running mate to the Olympic, as she replaced the Britannic. Some time before the Majestic had arrived, the Columbus had replaced the Titanic carrying the name Homeric and once and for all deleted the order of the Germanic. At last, White Star had their long awaited three-ship service to New York from Southampton. To prove her worthiness, the Olympic completed her fastest ever crossing in 1922 with 5 days, 12 hours and 39 minutes time only.

After Captain Hayes had left for the Majestic, the Adriatic’s former master, Captain Alec Hambleton took command of the Olympic. He would only stay for about a year, but during his time the new climate on the North Atlantic would become apparent. The Americans restricted the inflow of immigrants to only three per cent of the foreign born population. Suddenly, the ocean liners almost became obsolete, as they had to rely on business travellers and an entirely new class of people – the Tourist.

After the Hawke collision in 1912, the Olympic had been spared from major accidents, but the second major one occurred as she moved out from her Pier 59 in New York on March 22, 1924. Unwittingly, the Olympic backed right into the small Furness Bermuda liner Fort St. George, resulting in a serious collision. The Fort St. George suffered a broken main mast, considerable damage to her lifeboats, railings and decks over a length of 150 feet. The Olympic did not appear to have more damage than the scarred hull plates visible, but after her return voyage to Southampton it was revealed that the entire stern-frame was damaged enough to be entirely replaced.

One of the Olympic’s creators, Lord Pirrie, had died in June 1924 on a voyage from South America. The body was taken to New York where the Olympic took the coffin on board and sailed for Queenstown where the body would be transported from to Belfast where he was buried on the 23rd. Eight months later, Captain Hambleton left the Olympic in favour of Captain William Marshall. During his command, the Olympic would receive the third distress call in her career. The small steamer Ellenia requested assistance when the Olympic had sailed some nine hours off New York. When she reached the Ellenia within 15 minutes, she gave the message to Captain Marshall that she was not in any need of assistance. To make sure, the Olympic sent out one of the boats with Fourth Officer J. Law to speak eye to eye with the Ellenia’s master. When the lifeboat returned forty minutes later, Law confirmed that the Ellenia requested a tow to New York. As the smaller vessel was not in any immediate danger, and because of the fact that several French vessels were closing in nearby, Marshall took the decision to carry on with the voyage to Southampton.

The third class system was abandoned in 1925 when all these staterooms were remade into ‘Tourist Third Cabin’. This new class consisted of the best third class cabins and the less attractive second class staterooms. The price for a ticket in this new class would be slightly higher than a conventional third class ticket. In 1927, the IMM finally left the ownership of the White Star Line and the British Sir Owen Phillips bought the Oceanic Steam Navigation Company for £7,000,000. After being partly British and partly American during the whole of her existence, the Olympic was now purely a British ship. It was also during this time that the demand of the old class system declined, and in 1928 all Tourist Third Cabin staterooms were completely done away with, and replaced by ‘Tourist Class’. Other changes occurred in the first class dining room where the captain’s table was removed and a large dancing area fitted.

The next year’s September it was time for Captain Marshall to leave command to Captain Walter Parker. Marshall had enjoyed the Olympic so immensely that he became rather emotional when he was to leave her, and Captain Parker offered to take on the Majestic instead so Marshall could stay, but the latter replied: ‘I suppose I ought to feel honoured. She is, after all, the largest ship in the world, you know, Parker – but I am leaving the best to you, for all that’. And so it was – Captain Parker overtook command of the Olympic.

When on one westbound crossing on 18th November 1929, the Olympic experienced one strange event. When two days from New York, the whole ship suddenly started to shake for no apparent reason. Watchmen confirmed that there was no other vessel nearby so a collision could be excluded. As the engines were still running smoothly, the possibility of a dropped propeller blade was also out of the question. Surely, the crew shivered when they found out that they happened to be exactly above the Titanic’s grave some 12,000 feet below, but after some time the wireless men confirmed that there had been an underwater earthquake, causing the shaking. At the end of the next voyage, Captain Parker went into retirement and passed his command on to Captain E. R. White.

Back in 1927, a series of cracks along the Olympic’s superstructure had been discovered, but as they were not of a serious sort mending had been shelved. But when the matter was looked upon again in 1930, it was apparent that the cracks had developed badly. Knowing that a similar damage on United States Line’s Leviathan had cost £300,000, White Star did not want to spend that much money on an old ship like the Olympic. The necessary repairs consisted of having the damaged area covered with new plating. The Olympic was considered good enough for the next six months and when she showed worthiness after the period the Board of Trade signed for another six months. However, on November 9, 1932, the White Star Line admitted the Olympic to be old enough to have a limited service speed of 21 knots. In late 1932, Olympic went for an extensive overhaul that lasted for four months. When returning to service on March 1, 1933, her owners described her as ‘looking brand new’.

Later the same year, the declining White Star Line was forced to merge with the Cunard Line – their former arch-rival – forming the new Cunard White Star Line. The dominating part in the company would become Cunard with 62 per cent of the votes. White Star’s contribution was some ten vessels including Majestic, Olympic, the two new motor vessels Britannic and Georgic and the ageing Adriatic. All of these vessels were quickly put on the disposal lists except for the motor vessels. But before the Olympic would withdraw herself, another major incident had to be gone though.

By 1934, Captain White had been replaced by Captain John Binks. When in New York waters on May 15, 1934, the Olympic steamed through the extreme fog at a reduced speed of ten knots, but despite the slow speed, blasting the ship’s whistles and the lights, the Olympic was not able to spot the Nantucket lightship. At 11.06 a.m., the red hull of the lightship came into the Olympic’s view and Captain Binks immediately ordered the engines full astern. But it was too late. The immense Olympic cut the lightship in half making it into ribbons. At the time of the collision, the Olympic was making a mere 3-4 knots. Seven men on board the lightship had perished and only four survived.

This was not exactly what the Olympic needed in bad times like these. She was already considered to be removed from service, but now the merciless Cunard White Star management had taken the matter more seriously. The fact that they had withdrawn the much-loved Mauretania from service in 1934 showed that the end was near for the Olympic. In January 1935, it was announced that she would be withdrawn from service at the end of the spring. Under the command of her latest master, Captain Reginald Peel, the Olympic departed from Southampton for the last time on March 27, 1935 on her 257th and final round trip to New York. Noted among the crew on this very voyage was Frederick Fleet, who had been the Olympic’s sister-ship’s lookout one cold April-night 23 years earlier.

The next six months, the Olympic lay derelict at berth 108 in Southampton. There were rumours about a return to service, but the most reliable answer for a return was given by the Italian Government who eyed her as a possible transport for their East Africa campaigns. But as the Olympic was sold in September for £100,000 to Sir John Jervis the speculations ended. Sir John immediately re-sold the liner to Thomas Ward & Sons, the ship-beakers at Jarrow.

In the afternoon on October 11, 1935, the Olympic left Southampton for the last time as she steamed out of the ocean dock under the command of Captain P. R. Vaughan. She passed her running mates, the Majestic and Homeric, and gave them a last salute on the whistle as she lowered her houseflag. Two days later, the Olympic arrived at her destination at the River Tyne. She received a massive reception as every waterborne craft gave her their salutes. Five o’clock that afternoon she was secured at the spot where she would be broken up, and Captain Vaughan ordered ‘Finished with engine’ for the last time.

Before the dismantling process could commence, all interior fittings of interest were to be auctioned off. Buyers from all over Britain appeared, as they wanted to take part of some of the most beautiful fittings ever put on a ship. Much of it came to the White Swan Hotel in Alnwick, England where large parts of the first class lounge survive until this day.

The dismantling process took close to two years, and the last part of the Olympic’s once perfect hull was lifted out of the water in late 1937. She was the first of a class of liners that would astonish the world, and as fate would have it she was also the last of them.

Specifications

- 882.9 feet (269.68 m) long

- 92.6 feet (28.2 m) wide

- 45,324 gross tons

- Triple-expansion engines powering two wing-propellers, and one exhaust steam turbine powering the centre propeller

- 21 knot service speed

- Passenger capacity of 2,764 people

2 thoughts on “Olympic”

” Some of the most important vessels White Star had lost were Britannic, Titanic and Oceanic.”

Incorrect – Titanic was not sunk during WW1.

“All of these vessels were quickly put on the disposal lists except for the motor vessels.”

Incorrect, Georgic & Britannic, Doric & Laurentic were retained by CWSL following the merger. Doric and Laurentic were damaged in separate collisions in 1935. The damage to Doric led to her being scrapped, but Laurentic was repaired and served until the outbreak of WW2. She was torpedoed and sunk in 1940.

There is no mention of the plans for WSL to have the first 1000ft liner to be called ‘Oceanic’. Construction on the keel started in 1928 but was abandoned by 1929 due to the companies worsening financial situation.