1952 – 2000

Also known as Calypso, Calypso I, Azure Seas, and OceanBreeze

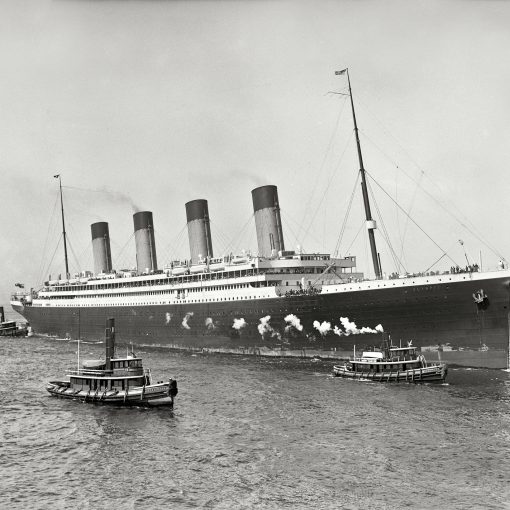

In the decade that followed in the wake of the Second World War, competition was soaring on the high seas. The ever-so-glamorous North Atlantic run was turning in great profits, but not as much due to emigrants as it had been earlier in the 20th century. Now, more and more people could afford a sea voyage for the pure sake of pleasure, not least illustrated by Cunard’s famous post-war slogan; ‘Getting there is half the fun’.

However, it was by no means everyone who could afford such voyages, and those who could were mainly Americans. In Europe, many nations were still recuperating from the hard times brought on by the war, a condition that would result in many setting out in search for a fresh start in a new country. But, with immigration restrictions in the United States, other countries such as Canada, South Africa, New Zealand and Australia became popular destinations.

But many of the ships that had been employed on this route before the war had been lost during the bloody conflict. Most shipping companies needed new tonnage to be able to compete, and in the early 1950s, Great Britain’s Shaw, Savill & Albion Line approached the revered Belfast shipbuilders of Harland & Wolff to order a new liner for their fleet. Yet this was by no means a liner like any other. As the builders and future owners drew up the plans for the new ship, a great many novel ideas were incorporated into the design. The company chairman at the time – Basil Sanderson – had come up with the idea of placing the engines and funnel aft. Being an entrepreneur rather than a ship architect, Sanderson’s idea sprung first and foremost from business reasons. This layout would free space for large passenger areas amidships, and thus sharpen the ship’s competitive edge. And to put even more emphasis on the passengers, this would be a ship completely devoted to them, carrying neither cargo nor mail.

It should be pointed out that it was not actually Mr. Sanderson who had invented the ship’s suggested type of design. Other ships, like Matson Line’s Lurline from 1908, had been fitted with such an engine arrangement. But this would be the first time that a ship over 20,000 gross tons would utilise it. And, as history would have it, this new liner would start an ‘engines aft’-trend, soon to be copied on great ships like the Rotterdam and Canberra. Today, every passenger ship is built this way.

Still, this could not have been anticipated at the time the plans were being made. In fact, Sanderson’s ideas were not well received among the decision makers of Shaw, Savill & Albion, who actually opposed them at first. But Sanderson was convinced that he was on the right track, and following much persuasion he was eventually given approval to proceed with the project on July 16th 1952. The estimated cost was £3,546,000.

A little more than six months later, on January 28th 1953, the keel of the new liner was laid down on Harland & Wolff’s no. 2 slipway. As the months went by, the new ship began to take shape under the hands of the workers. So far, she was only referred to as yard no. 1498, but the work of finding a suitable name for her was well under way. Being intended for the run to New Zealand and Australia, Basil Sanderson felt that the name should reflect this aspect of her service. And there was also the question of who was going to christen the new ship. In an attempt to solve these problems, Sanderson sent a letter to HRH Queen Elizabeth II. Asking for her consent to launch the new liner, he also included three suggestions of names for the Queen to choose from.

To the joy of Mr. Sanderson, the Queen replied that she would be happy to launch the ship. As reported by Pathé at the time, it was the first time that a British sovereign would christen and launch a merchant vessel. For the name, the Queen had chosen Southern Cross – the constellation of stars found on the national flags of both Australia and New Zealand. And so, work continued on the ship until the day of launch finally arrived on August 17th 1954. However, dark clouds were looming in the sky, literally as well as figuratively. It was a dull grey dawn in Ulster, with drizzling rain that fell more heavily as the morning wore on. What made matters worse was that the weather was equally bad in Scotland, where the Queen was staying at Balmoral Castle at the time. She was supposed to fly from Dyce to Aldergrove, fourteen miles from the yards of Harland & Wolff, arriving in good time at the ceremony which was scheduled for 1.15 pm.

But the poor weather conditions lead to the Queen’s flight being delayed, and Basil Sanderson was informed that she would probably arrive as much as 30 minutes late. This was terrible news. The blocks that had held the ship in position had been knocked away in preparation for the launch, and it would not be safe to delay it for more than half an hour. If the Queen could not arrive on time, the ship would simply have to be launched without her.

Fortunately, Sanderson was not the only one who was aware of the precarious situation. When the Queen left Aldergrove by car, she was fifteen minutes behind schedule. But the police cleared the road to the shipyard, and the Queen instructed her driver to exceed the speed limits as the party raced through the streets of Belfast to make it there on time. Fortunately, their efforts were not in vain. Having regained the lost fifteen minutes during the speedy drive, the Queen arrived just on time, accompanied by ‘God Save the Queen’ played by the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers as she stepped out of the car.

Before sending the vessel down the slipway into the water, the Queen spoke the traditional words: “I name this ship Southern Cross. May God protect her, and all who sail in her.” She then pulled a lever, and released the bottle (that had been carefully aimed well in advance of the ceremony), smashing it across the bow, and the mountain of steel began moving. Sliding into her rightful element to the cheers of the gathered crowd and whistles from nearby boats, the great hulk was soon brought to a halt and moved to her fitting-out berth where she would be completed. The Southern Cross was born.

A few months later, the fitting-out had been completed, and the ship was ready to go through her acceptance sea trials. These were performed perfectly satisfactory off the Isle of Arran, with the ship achieving a maximum speed of 21 knots over the measured mile. And so, Shaw, Savill & Albion Line was happy to take delivery of the Southern Cross on February 23rd 1955. Her debut on the run to Australia and New Zealand was still one month away, and so this time was put to good use with a few so-called shakedown cruises, to familiarise the crew with their new ship.

Then, at last, Southern Cross was ready to embark on her premier voyage on her intended service. On March 29th 1955 she left Southampton, with an itinerary ahead that was fairly unique. She would sail on a continuous round-the-world service, going from Southampton to Las Palmas, Cape Town, Durban, Fremantle, Melbourne, Sydney, Auckland, Wellington, Fiji, Tahiti, the Panama Canal, Curacao, Trinidad and back to Southampton again. With a projected sailing time of 76 days, the Southern Cross would make four such voyages on an annual basis.

Making her way ‘down under’, the Southern Cross must have been a lovely sight. Her profile was daring and innovative, but she still conveyed the majesty that only a great ocean liner is capable of. Sporting a grey hull and a superstructure painted in a light shade of green, she looked as exclusive as the route she was sailing. But, the real exclusiveness of the ship was found beneath the exterior appearance, in the comfortable areas devoted solely to her passenger compliment.

Being a single-class vessel, all of the passenger areas on board Southern Cross were accessible to economy-fare travellers. That said, there is no question that the ship offered a very high standard of comfort. Nearly the whole ship was air-conditioned, apart from the bridge and most of the crew accommodation. The passenger cabins ranged from 1- to 6-berths, and were painted in either blue or cream tones. All cabins had running hot and cold waters, but only the more expensive ones offered the luxury of private facilities. Inside cabins, which did not have a window or porthole, were fitted with circular lights that were switched on at 7:00 am, with increasing intensity to mimic the rising sun. Throughout the ship, ‘Airiness with a sense of homeliness’ had been used to achieve an atmosphere of ‘Comfort with utility’.

Public passenger areas included features such as the Forward Lounge, the Mayfair Lounge, a small library and Writing Room, a Smoking Room and two restaurants, the forward one seating 390 people and the aft one capable of 192. Furthermore, there was the Cinema Lounge, complete with a balcony and 17-foot ceiling. Serving as both a lounge and cinema as well as a concert and dancing venue, this was a popular place on board.

Above decks, the modern engine arrangement had paved the way for some 45,000 square feet of unobstructed and open deck spaces. Just forward of and below the bridge was the Sun Deck, housing a 22 by 18-foot pool, along with a smaller children’s pool. There was also a larger indoor pool below decks, but one’s guess must be that the outdoor one had to be more popular while the ship travelled along warmer latitudes. For those who preferred a healthy stroll instead of a swim, there was the fully encircling passageway situated on the Promenade Deck as well as the sheltered promenades on Lounge Deck. And to let the passengers enjoy these amenities to the full, the risk of Mal de Mer had been minimised with the ship being equipped with stabilisers.

And so, the Southern Cross settled into her Shaw, Savill & Albion service, enjoying great success. Her fleet mates included the magnificent Dominion Monarch of 1938, which despite being very popular, needed to be replaced by new tonnage. Subsequently, in 1962 the 24,733-ton Northern Star entered service. Built by Vickers-Armstrongs, she was a slightly larger ship of the Southern Cross’ basic design. This, if anything, was proof of the success of Basil Sanderson’s original vision. Once her new fleet mate had settled into service, a significant change was made in the Southern Cross’ duties. Her itinerary was inverted, going west via Panama outward, and then homeward via New Zealand, Australia and South Africa as the new Northern Star assumed her previous route. With this, Shaw, Savill & Albion Line really lived up to their reputation of being a company that brought Britons to Australia, and returning with Australians on holiday.

However, as time went on, the competition from the airliners was getting harder and harder. The spotlight sea lane on the North Atlantic had already been more or less taken over by jet travel by the mid-1960s and although the Australasian run was spared at first, it too started to suffer under the jetliners’ roars as the 70s drew nearer. As a consequence, it became no longer financially viable to keep the Southern Cross and her fleet mates in round-the-world service over the entire year. Instead, starting in late June of 1971, the Southern Cross was also employed doing Mediterranean cruises out of Liverpool.

Unfortunately, this scheme met with only limited success, probably much due to her lack of private facilities in all cabins. After only some five months as a Shaw, Savill & Albion cruise ship, the Southern Cross was taken out of service and laid up at Southampton in November 1971. As a replacement, the company purchased Canadian Pacific’s Empress of England, renamed her Ocean Monarch and put her in service along with the Northern Star. But, as time would have it, the company lasted for only a few more years, with both ships sent to the breakers in 1975.

Overall, these were hard times for British passenger liners. In April of 1972, the Southern Cross was moved to an anchorage in the Cornish River Fal, only to spend continued, uncertain time in lay-up. As other unwanted liners were towed off to the scrappers’ yard one by one, it became probable that the same would happen to the Southern Cross if no one would express any interest in her. Luckily, someone did.

In January 1973, the ship was sold to Cia de Vapores Cerulea SA of Ithaka, which was the trading name of the Ulysses Line Ltd. Renamed Calypso, the ship was then sent to Piraeus that same March. There she was to go through an extensive refit into a proper cruise ship, and much work needed to be done. First of all, all passenger cabins were rebuilt with private facilities. Otherwise, her basic interior layout was retained, but restyled into a ‘70s minimal’ style, with bright colours and the original wood panelling replaced by modern, fireproof chrome and plastics. Painted white, remeasured at 16,500 gross tons and with her passenger capacity reduced to 1,000 people, Calypso was ready to re-enter service after two years of refitting.

On April 25th 1975, the Calypso inaugurated her Mediterranean cruise service out of Piraeus. But, this service only lasted for a few months, before she was chartered to Thomson Cruises, and used for cruising out of Tilbury and Southampton. Seeing much variation, the ship was also tested on experimental cruises from New York to Bermuda, as well as a season of Alaskan cruises in 1980. That same year, she was renamed Calypso I. As such, she would not see much service though. After spending her summer season in Alaska, she was again sold, this time to the Eastern Steamship Lines Inc. of Panama, and given the new name Azure Seas. The Eastern Steamship Lines had been operating a very successful service in the Caribbean, doing three- and four-night cruises between Miami and Bahamas with the venerable old Emerald Seas, originally the US troopship General W. P. Richardson. With the Azure Seas, the company established an equivalent west coast operation under the name Western Steamship Lines Inc.

But before she started this new career, the Azure Seas was renovated in order to freshen her interiors once more. As before, the general layout was retained, and the changes were mostly cosmetic ones. However, a new casino was installed in place of the Cinema Lounge and the indoor swimming pool was turned into a night club. When finished, the ship was deployed on her new itinerary, doing three- and four-night mini cruises to Ensenada and Catalina. After a somewhat slow start, the Azure Seas soon became hugely successful, to the company’s delight. She had soon attracted a loyal following, earning a very good reputation of being a ‘friendly ship’. Her success had soon attracted others who wanted their piece of the action, and it wasn’t long before the whole west coast ‘party cruise’ phenomenon was a fact.

In 1986, the competition led to the merger of Western Steamship Line and their rival Sundance Cruises. The new company was dubbed Admiral Cruises, and the Azure Seas was kept on her profitable run. She remained with the company for another five years, spending the last months cruising the Bahamas, stationed at Fort Lauderdale. But, that same year, the roaring competition in the booming cruise market led to another amalgamation. Admiral Cruises was purchased by one of the industry’s giants –Royal Caribbean Cruise Line. Unfortunately, they had no interest in older ships like the Azure Seas, who was immediately put up for sale.

At this point, the Azure Seas had reached her 36th year of age. But she was still in good shape, and the good reputation surrounding her was enough reason for others to be interested in taking over her. One of these companies was the Dolphin Cruise Line, which already operated a two-ship service with two veteran ships – the Dolphin IV (ex-Zion) and SeaBreeze I (ex-Federico C.). Now they were looking for a third ship, and the Azure Seas was a perfect choice. Once again renamed, she now became the OceanBreeze and was deployed on seven-night cruises from Aruba in 1992. There she stayed for another four years, until she was moved to the company’s Florida and New York based cruise service. And as the 20th century drew to a close, there were more changes in store for the veteran liner. In 1997, Dolphin Cruise Line, Seawind and Premier Cruises – all of them part of the parent company Cruise Holdings – were put under the same flag and labelled Premier Cruise Lines Inc. The new company adopted the livery of a dark blue funnel and blue and gold hull livery, a set of colours that looked very smart on the OceanBreeze.

However, the ship would stay in service for Premier for just another two years. Having been used for Caribbean cruising, the OceanBreeze was chartered to the newly formed Imperial Majesty Cruises in 1999. Being the sole ship of the company, she was then deployed doing two-night sailings on a year-round basis from Fort Lauderdale to Nassau. The Premier logo on the funnel was replaced by a white crown, but the blue and gold hull colours were retained. And except for the operators and itinerary, very little changed with the ship. Even the Premier Line crew was kept on. Once again, the remarkable ship displayed her ability to generate a well-liked product. Just as during her tenure as Azure Seas twenty years earlier, the OceanBreeze was soon enjoying great popularity as the only ship of Imperial Majesty Cruises. In fact, the venture was so successful that Imperial Majesty decided to end the charter arrangement and purchase the ship outright in late 1999.

And as the 20th century came to its end, the OceanBreeze’s popularity continued. Things were going so well that her owners decided to invest in bringing her interior fittings up to date. In October of 2000, the OceanBreeze was sent to Newport News, where a $3,500,000 refit replaced all of the soft fittings, carpeting and draperies on board.The OceanBreeze remained in service for Imperial Majesty Cruises, still employed on her two-night itinerary between Florida and Bahamas. Being one of the few classic ocean liners left in service, she offered a product that greatly differed from the glitzy, Las Vegas-style voyages found with giant companies such as Carnival and Royal Caribbean.

Outwardly, her graceful lines still conveyed so much more beauty than the modern, wedding-cake ships that are crowding the seas today. Internally, the ship had seen several face-lifts, but still held the ambience of a classic liner. Many of the features from her Shaw, Savill & Albion days as Southern Cross were still recognisable, for example the 88-seat Mayfair Lounge, with its original wood-framed doors intact. Of course, some features had been added over the years to make the ship more competitive on the modern cruise market. The topside Sun Deck had been equipped with a Jacuzzi and swimming pool, and both a disco and casino had been added to give the passengers more party opportunities. But the ship still had its teak decking – a classic liner feature if any – and it was accordingly kept spotless by the crew.

And so, the OceanBreeze continued to sail on as a very profitable vessel. There were legitimate worries about the new SOLAS (Safety of Life at Sea) regulations that would come into power in 2010, and that they might make it difficult for the ship to remain in service, but even if that were to happen it was hoped that she would still have a few good years of service left ahead of her. Being something as unusual as a British-built, steam-powered passenger ship operating in the Caribbean in the twenty-first century, it would certainly had been nice if she had been able to stick around for as long as possible. However, things would not last much longer. In July of 2003, she was suddenly sold for scrap when Imperial Majesty Cruises got a cheaper lease on the Caribe I (originally built in 1953 as the Olympia). Only a few months later, in November 2003, the old Southern Cross was run aground at high tide on the coast of India, where she was to be dismantled.

In a way, it is ironic that the Southern Cross, a ship that with her innovative engine arrangement in a sense was a forerunner of most modern ships, managed to stay around for her piece of the pie for as long as she did. Just like the Rembrandt (ex-Rotterdam), she was a ship that was looked upon as daring and progressive when new, but eventually came to represent the classic ocean liners, a breed that will probably never return to the high seas.

Specifications

- 604 feet (184.5 m) long

- 78.4 feet (24 m) wide

- 20,204 gross tons

- Geared steam turbines turning two propellers

- 20 knot service speed

- Passenger capacity of 1,160 people

Film Footage

| Special thanks to Stephen Berry, who so kindly assisted with his knowledge and collection of Southern Cross material. |

8 thoughts on “Southern Cross”

Sorry. Forgot to say that My husband and I with other collegues sailed on the Southern Cross, from Liverpool Docks down to London, before she did her maiden jopurney..

I was then expecting my first baby…Jennifer. Had lots of fun and fantastic dinner and dance….Travelled first class on train, to Liverpool from London. Rita Moss (age 101…)

Shaw savill. John Macmillan was the chairman at the beginnin. My husband” Micky Moss” worked in accounts and did statistics. He left in 1962. I am his wife and am now 101 year old. If you belonged to Shaw Savill, it was with everyone, a way of life. Rita Moss.

I sailed on the Cross from Trinidad to Liverpool in 1960, a wide-eyed 7-year-old about to join the Windrush Generation. It wasn’t an auspicious beginning, we spent the whole voyage locked away in quarantine, when my brother caught chicken pox! I really enjoyed your article, brought back many memories. I’ve written this piece below, much of it ‘borrowed’ from yours – with full acknowledgement, of course. I lived in Barbados in the nineties, and vaguely remember a cruise ship called Calypso, never dreaming it was my old Cross!

Hi can anyone help me with dates and photos if possible we went from Sydney to Miami in 1965 around October on the Southern cross as I was only eight I can’t remember where all we docked and dates thank you in advance

Wow !! What a Great catch up, as the “SX” was the first Ship I traveled on ex Wellington April 1965, On settling into our inside cabin there was a knock on the door I opened it and there was a Very Large person looking for me, He was the Sargent of Arms and had met my Dad who was having a Beer with senior Customs officers the night prior sailing, thus was ready to give me some advice. I was informed it would be a very rough voyage to Sydney and it was suggested that if I felt unwell mid morning I should have a small Brandy as this would settle my stomach, yes it did, so each morning at 1100 we would have a Large Brandy just to keep well all day. I enjoyed my rough passage across the Tasman and that voyage has encouraged me to take many mainly Cruises over the past 50 years, and prepared me for a few Rough Sailings since.

It was interesting that on my return to Wellington I was transferred to Whangarei with Dalgety Travel and also took on the Roll in Dalgety Shipping the SSA’s Port agent for Whangarei & Opua, thus it’s great to be kept up to speed with ships like the Southern Cross, thus my membership of the SSA Society. Now residing in Kerikeri and on a recent visit to Opua the old wharf has died.

I worked for Shaw Savill & Albion Co Ltd in New Zealand from January 1959 to July 1975 when the passenger division was closed. In 1988 I took a small group of 24 ex staff and partners to Los Angeles to cruise 4 nights on the Azure Seas to San Diego and Ensenada. We had a great time. I should mention that the “Mayfair Lounge” was the smoke room and at the aft end of the promenade deck was the very popular Tavern Bar. Also, by that time, the indoor swimming pool had been turned into a disco/night club and the former cinema lunge was a casino. All of us loved the Southern Cross.

I’d like to offer a correction to the following line in this article.

“To the joy of Mr. Sanderson, the Queen replied that she would be happy to launch the ship. In fact, this would be another ‘first’ for the new liner, since it would be the first time that a reigning monarch would launch a passenger ship.”

This was not the first time a reigning monarch launched a passenger liner. Please refer to the launch of the SS Oranje and the SS Neiw Amsterdam in 1938. Both ships were launched by Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands many years prior to the launch of Southern Cross.

I wanted to promptly make this clarification because on Southern Cross’ Wikipedia page, this article is cited when referencing that the ship was first to be launched by a reigning monarch, Thus perpetuating a rather significant misinformation. Im working on having that part edited out of the Wiki page as well.

Thought that this would be of assistance. Thanks.

Thank you for bringing this error to our attention!

This article was originally written more than a decade ago, so I’m not sure where the information originated from. The claim should have been more specific, since it was the first time that a reigning British monarch launched and christened a merchant vessel, as reported by a Pathé newsreel. It still doesn’t take away the fact that Queen Wilhelmina beat her counterpart to the punch by about a decade and a half, though!

In any case, the error has now been corrected and I hope it will not propagate any further. Again, thanks for your help!