1930 – 1966

Also known as Empress of Scotland (II) and Hanseatic (I)

By the 1920s, the world had gone through decades of significant changes. According to F. Scott Fitzgerald, “all gods were dead, all wars were fought and all faith shaken”. Although history would soon prove him wrong, it was true that the world was no longer the same. Advances in the field of communication and transport had contributed to shrink the world, and to travel across the globe was now a far more easy and comfortable task than it had been only fifty years ago.

The busiest and most profitable sea-lane was the North Atlantic, where shipping companies such as Cunard and White Star were earning a fortune. But, the most extensive and impressive network of transport was that of the Canadian Pacific Railway Company. Operating ships on the North Atlantic, they linked Britain with Eastern Canada. A railway relayed passengers across to British Columbia, terminating at the port of Vancouver. From there, ships of the company’s Pacific fleet carried travellers to the Orient.

In the late 1920s, Canadian Pacific decided to order a new vessel for their Pacific operations. The contract was signed with the Glasgow firm of Fairfield Shipbuilding & Engineering, who soon set about constructing the new ship.

On December 17th 1929, the day had come to launch the new ship. With a prospected size of about 25,000 gross tons, this was indeed a proud day for Canadian Pacific. The launch went well, and work would soon begin on fitting out the new ship, which had been named Empress of Japan.

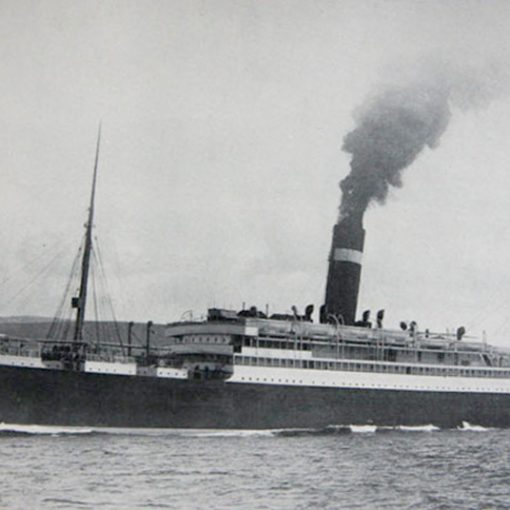

Six months later, when the summer of 1930 was approaching, the new Empress of Japan was to go through her sea trials. Sporting a classic steamship-look, she had three funnels painted in familiar Canadian Pacific yellow. Her promenade deck had not been enclosed, revealing that she was intended for the warmer Pacific run. Down in the engine room, the ship’s engineers were getting ready for the engine trials. Empress of Japan had been designed with geared turbines, capable of 34,000 shaft horsepower.

The engines performed very well, and the ship managed to reach a top speed of 23 knots with the engines running at maximum power. Thus, the ship’s sea trials had been carried out successfully, and she was officially delivered to Canadian Pacific on June 8th, 1930. It was only a short matter of time before she would enter service for her owners.

And so, on June 14th, the new Empress of Japan left Liverpool on her maiden voyage, bound for Quebec. From there, she proceeded to Vancouver to take up station and commence her intended trans-Pacific career. Her first Pacific voyage commenced on August 7th, when she left Vancouver for Yokohama. Known as ‘The Queen of the Pacific’, the Empress of Japan had soon broken the Pacific speed-record. She quickly became known as the fastest, largest and finest liner on the route.

Originally, Canadian Pacific had planned to build a sister to the Empress of Japan in order to balance the schedules. But by now the Depression was affecting the shipping business so badly, that the company had to focus on their coming new transatlantic flagship – the Empress of Britain. So, the Empress of Japan was destined to be a one-off. In spite of this, she continued her regular sailings through the 1930s, always enjoying a very good reputation. But in 1939, the world was once again plunged into war when Germany invaded Poland on September 1st. Two days later, Great Britain and her allies declared war on the Axis powers, and this conflict would soon escalate into World War II. Once again, the great liners of the world would be called in to serve their nations in time of war.

On November 26th 1939, the Empress of Japan was requisitioned for trooping duties. Instead of offering comfortable amenities for travelling passengers, she would now be used to transport soldiers to the battlefields across the globe. For the following year, she served this purpose well without seeing any actual action. But, on November 9th 1940, while sailing off Ireland, she was dive bombed by enemy aircraft. With great skill and luck, the crew on board Empress of Japan managed to evade the bombs, and the ship could escape unharmed.

Yet another year later, on December 7th 1941, an event took place that would affect the Empress of Japan’s further career. When Japanese forces attacked the American Pacific base Pearl Harbor, they immediately made enemies of the United States and their allies. From this day, there were massive protests about using an enemy name for a troopship. At the time, name changes of ships were prohibited, but Winston Churchill was of the opinion that in this case, the prohibition was ‘a nonsense’. It took a little more than ten months, but on October 16th 1942, the ship was renamed Empress of Scotland.

Sporting her new name, the Empress of Scotland continued her war duties. When peace was finally achieved in 1945, she was kept on for repatriation work, and it wasn’t until May 3rd 1948 that she was released from transport service. During the conflict, the Empress had steamed some 600,000 miles, and she was in desperate need of a refit before she could re-enter passenger service again.

Naturally, this was the case with nearly every passenger vessel that had survived the war. This, plus the shortage of funds and material, forced the Empress of Scotland to simply wait for her turn to go through a refit. Finally, in October of 1948, she was sent back to her builders for a much-earned refurbishment. The first intention was to put her back in her regular service in the Pacific, but it was soon decided to place her on the North Atlantic run instead. For this, her promenade deck was glass-enclosed to better suit the Atlantic weather. Also, her original passenger accommodation of First, Second, Third and Steerage classes were altered to just First and Tourist.

It took a while before the work was finished, but on May 5th 1950, the Empress of Scotland set out on her first post-war voyage, from Liverpool to Quebec. Outwardly, she was very much alike her pre-war self. The white hull was there, but the three funnels now sported the new CPR livery, adopted in 1946 – yellow, with the company flag superimposed.

The Empress of Scotland soon settled into her new service. She ran on the Liverpool-Greenock-Quebec service during the summers, and in the winters she was sent off cruising the West Indies out of New York. In April of 1952, the ship’s masts were shortened in order to allow her to pass under the Quebec Bridge and continue to Montreal, which had now been dredged to her draught. On May 13th she made her first sailing from Liverpool to Montreal.

The ship continued to serve Canadian Pacific through the 1950s, but circumstances would soon see her leave the company. In 1956, the brand new Empress of Britain entered service, followed by her sister Empress of England the next year. Suddenly, the Empress of Scotland was an old ship compared to her fleet-mates, and she was subsequently laid up at Liverpool on November 25th, 1957. She was later dry-docked at Belfast and put up for sale by the company.

However, an inspection showed that the ship’s hull and machinery were in very good condition, and it did not take long before a buyer materialised. On January 13th 1958, the ship was sold for $2,500,000 to the newly formed Hamburg-Atlantic Line. Six days later the ship left Belfast, flying the German ensign and renamed Scotland for the voyage to Hamburg. Upon arrival, she was sent to the yards of Howaldtswerke, where she was scheduled for an extensive refit.

In July of 1958, the ship emerged from the yard. Renamed Hanseatic, her name was certainly not the only new thing about her. The original three funnels had been replaced by two larger ones, and her hull had been rebuilt to a more streamlined design. This, and the black, white and red colours of her new owners made it quite difficult to recognise her.

On July 21st that year, the Hanseatic set out on her first voyage from Cuxhaven to New York, with calls at Le Havre, Southampton and Cobh along the way. Although owned by the Hamburg-Atlantic Line, she was managed by the more experienced Hamburg-America Line. Hanseatic had soon earned a loyal following as one of the finest West German liners, and she continued her North Atlantic service in the summers, while doing cruises during the off-season. This service was maintained well into the 1960s, but unfortunately the end was now drawing near.

On September 7th 1966, the ship caught fire in the engine room, while in New York. The fire caused serious damage, but efforts to extinguish it soon succeeded in doing so. Hanseatic’s machinery was severely damaged though, and the ship was forced to leave New York under tow of the Bugsier tugs Atlantic and Pacific on September 23rd. She was sent to the Howaldtswerke in Hamburg for repairs, but an inspection found her to be beyond economic repair. Instead, the Hanseatic was laid up at Hamburg, awaiting her fate. On December 2nd 1966, the inevitable decision was made. She was sold for breaking up to the firm of Eisen & Metall AG of Hamburg.

Specifications

- 666 feet (203.5 m) long

- 83.7 feet (25.6 m) wide

- Originally 26,032 gross tons, 30,030 gross tons when rebuilt as the Hanseatic

- Geared turbines turning two propellers

- 21 knot service speed

- Passenger capacity of 1,173 people as originally built, reduced to 708 during 1948 refit

One thought on “Empress of Japan (II)”

Herbert James Ferguson (Grandfather) 1880-1952

1930-1930

Empress of Japan (II)