1930 – 1938

Back in 1912, the French Line had added the fantastic four-funneller France to their fleet of liners. She became an immediate success, and her spectacular interiors were talked about for decades. With this ship, the French Line – or Compagnie Générale Transatlantique, CGT – had given themselves a secure place among the leading shipping companies on the North Atlantic. The France was followed by the Paris in 1921 who became a ship of equal success. The ship that would put the world’s attention on the French Line came six years later – she was the Île de France and became a stunning success. Her fabulous Art Deco-inspired interiors attracted passengers from all over the world with its entirely new style. The French Line had started a new era in ship interiors.

In 1925 a somewhat smaller ship entered service within the French Line. She was the De Grasse and would team up with the larger ships of the line. This ship was never intended as a record breaker, and would only be able to reach a service speed of 17 knots. Still, the De Grasse was quite expensive to run with her steam turbines. CGT began to consider a new type of engines – Diesel ones.

Diesel is far less expensive to run, and the French Line had looked upon the Diesel-powered Swedish-American liner Gripsholm, who had entered service in 1925, with interest. By the later years of the 1920s, CGT came up with the first plans of building an entire new type of intermediate liner. The new liner would be powered by Diesel-engines, her interiors would resemble those of the Île de France and her exteriors would be a first, careful peek of what would come up years later. The new liner would be heir of the De Grasse, but she would stand out as more luxurious – she would be somewhat larger than the 1925-built ship, but the passenger capacity would be somewhat lower; a great concept when it comes to passenger comfort.

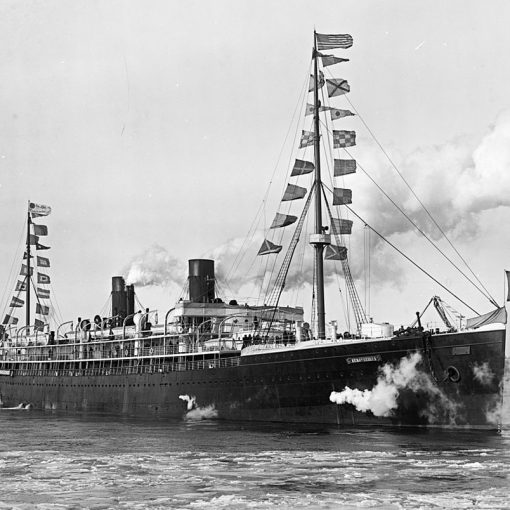

Construction of the new liner started out on the Penhoët shipyard in St. Nazaire in May 1928. She was constructed next to the Compagnie Sudatlantique’s L’Atlantique. A year later, on May 9, the ship was launched and christened Lafayette. The fitting out started immediately and on April 4 the following year the ship was ready for her sea trials. The speed test showed that the Lafayette lived up to the expectations of CGT, and more – she exceeded her predicted top speed of 18.25 knots with 0.05 knots.

The Lafayette’s engines had proved a success. True, the ship could not match the 24 knots of the old France or the Île de France, but in an economical aspect the ship was more than satisfactory. The four Diesels – two from Penhoët and two from MAN – generated 18,000 BHP and were geared to the four screws, which pushed the ship to her 18-knot service speed.

The Lafayette’s maiden voyage was scheduled to take place on May 19, but the week before she set off to New York, the Lafayette cruised in European waters as a final rehearsal. For the premier voyage, the famous Marquis Henri de Dampierre had booked a ticket in order to travel distinctive to an American Memorial Foundation meeting. The Marquis was the descendant of the famous Lafayette who helped the Americans during the break from the British Empire in the late 18th century. When Lafayette had arrived at New York, a masquerade was arranged on board her at her Pier 57. To remember the deeds of the Marquis’ forefather, the theme was Revolutionary. CGT had asked the Marquis to choose the Lafayette for the crossing because of his very appropriate heritage. He had gladly accepted and on the return voyage, the Marquis chose the France. The commander on the Lafayette’s first voyage was the experienced Captain Jules Chabot who had been in CGT for more than twenty years.

The Lafayette’s interiors were clearly inspired by those of the Île de France, but the former ship’s were more restrained. The old fashion of heavy draperies and plush furniture was entirely gone on board the Lafayette. Instead metal furniture and plywood was used extensively throughout the ship. This new type of fashion was not only good when it came to being modern – the metal made the Lafayette a very fireproof ship compared with other ships of the day. The new material was also strong and ensured a minimal cost in maintenance and repairs. Another special feature on the Lafayette – as on any CGT-vessel – was her kitchen. The French Line always had a special touch when it came to food.

After her maiden voyage, the Lafayette settled in a distinctive career on the North Atlantic as the largest motor ship in French Line service. In 1932 she was joined by her much-alike running mate Champlain. Basically, she was of the same appearance as the Lafayette, but she had some external modifications. Her bow was given a generous rake, and her decks were remarkably uncluttered. The single funnel was rather distinctive with a slanted smoke-deflector top. She was the first taste of what CGT had for the future. Some of the exterior appearances on the Champlain, like the bow and the stern and the uncluttered decks were later incorporated on the breathtaking Normandie, who arrived in 1935.

Just like any other ship, the Lafayette had her share of bad luck. On March 19, 1934 she limped into Plymouth harbour some eight hours late after an encounter with a fierce storm on the Atlantic. The damage consisted of over fifty smashed promenade deck windows. There were also some passenger injuries, but no casualties. The rotten luck continued on January 18, 1935 when the Lafayette accidentally collided with a tugboat when in harbour. The liner still continued with her voyage, even though some of her stern plates had been damaged. CGT’s given reason for the accident was fog, but several passengers reported that the Lafayette actually had been aground and the tugboat merely helped the Lafayette out of the situation.

In 1936, the Lafayette’s commander, Captain Etienne Payen de la Geranderie was appointed to the Paris. The Lafayette’s new commander was Captain William Vogel who came directly from the Colombie.

The year of 1937 was to be the last full year for the Lafayette. On May 4, 1938 the Lafayette was being overhauled at Le Havre. Accidentally, oil had been spilled on the furnace room floor and it started to burn when the furnaces were being filled. The fire quickly spread to one of the fuel tanks and soon the situation was way out of control. Within short, the fire had destroyed the electrical switchboard, which resulted in that all the lights failed. This made fire fighting all the more difficult, and soon every man with a common sense realised that the Lafayette was doomed. At about 12 am, the heat became so intense it exploded compressed air chambers in the engine room. The poor Lafayette suffered these explosions until 4 am, when they finally ended. The burnt out shell of the former luxury liner could not possibly be of any use to the French Line. They sold the ship to breakers in Rotterdam to where she was soon towed.

Specifications

- 610 feet (186.3 m) long

- 83 feet (25.4 m) wide

- 25,178 gross tons

- Four diesel engines powering four propellers

- 18 knot service speed

- Passenger capacity of 1,077 people