1965 – 1991

After the devastating First World War, the world found itself in severe shock. Close to everything had been destroyed in enemy raids, and now Europe had to start rebuilding itself. The great shipping nations such as Great Britain, France and Germany gave priority to their merchant fleets highly, and soon the world saw fantastic liners such as Queen Mary and the Normandie upon the seven seas. Further down in Italy, the trend was followed, and the stunning running mates Rex and Conte di Savoia were created. The first of these two liners became famous for her speed, and she even had the Blue Riband in possession for a while.

But before Europe had settled down completely after the war, another threat from the Germans seemed to rise. In September 1939, World War II started and went on raging for almost another six years. When the dreadful hostilities finally came to an end in 1945, the merchant fleets were – once again – badly erased. Since they had been used for military purposes they had been desirable targets for the enemy. Both of Italy’s flagships, the Rex and the Conte di Savoia had been victims of enemy aircraft bombing. They were both considered too expensive to rebuild, and were subsequently sent to the scrapyard. Once again, the merchant fleet had to be reconstructed.

Italy decided to start rebuilding their fleet with more moderate sized vessels. In 1952 the much famed 29,000-tonner Andrea Doria hit the waves, and shortly after that her running mate Cristoforo Colombo followed. However disaster struck in 1956, when the Andrea Doria was accidentally rammed and sunk by the small Swedish liner Stockholm. By 1960, a replacement for the Andrea Doria was finished and named Leonardo da Vinci. With her 33,000 gross tons she was the largest liner constructed in Italy after the war.

At the same time, Italy’s interest in another great ocean liner seemed to grow. Since the jet airliner had not yet had a great impact on the Mediterranean area, it still seemed to be a profitable idea to construct new giant ocean liners. The Italia Line opted for a pair of liners to operate between Genoa and New York. Actually, this was the first time since 1929 that a large genuine sister set had been ordered. Famous pairs such as Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth, Rex and Conte di Savoia had rather been running mates than identical sisters.

A new Italian trend was to name the county’s vessels after famous historical persons. The first of the new pair – who was being built at the Ansaldo Shipyards in Genoa – was decided to be named Michelangelo after the famous Renaissance artist. On September 16, 1962, the Michelangelo was launched. Attending at the ceremony was a representative from the Roman Catholic Church who gave the ship an official blessing. In April 1965, the brand new ship was ready for her sea trials, which she performed flawlessly, and a month later she set out on her maiden voyage to New York, which she reached on the 20th.

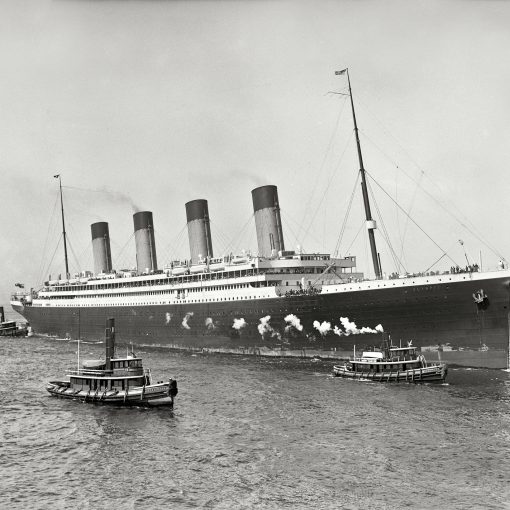

After many years of looking enviously on other nations, Italy could now finally boast their new champion. The ship was constructed with speed in mind; she would be able to maintain a good 27 knots as service speed. But the desirable Blue Riband was deliberately left to remain with United States Lines’ United States. The size of the ship was also something the Italians could be proud of. Both Michelangelo and her newly born sister – the Raffaello – exceeded 45,000 gross tons, and with a length of over 900 feet few other ships matched these two in size.

The external design of the Michelangelo was something quite new. Something unusual for a liner was that her hull was painted in white instead of the conventional black. From the beginning it was actually decided to use black as hull-colour, but white was decided upon when the advantages of the colour showed itself. For instance, white is more resistant in the Mediterranean warm climate and white gave passengers a hint that this ship might offer the same amount of luxury as many of the new, white cruise ships that had become more and more common everywhere in the world. The two funnels were of an entirely new sort. Of course, their practical use was excellent beyond perfection, but the external result became that of two giant cages on top of the superstructure. They were situated a bit far back so it almost seemed as if the Italia Line instead had wanted three funnels originally.

The interiors of the ship had left the classical touch that the Conte di Savoia had sported, behind. Michelangelo was clearly affected by Art Deco-style, and the trend set by the Île de France in 1927 had now reached the Italian ships to the full. One of the most liked features on board was the 489-capacity cinema. Added to this, the ship had thirty other public rooms in which the passengers could make each other’s acquaintance. In all the ship had six swimming pools. Three of them were for children, but the remaining were full-scale ones with heating utilities when the weather turned chillier.

On December 31, 1965 the Michelangelo’s first winter overhaul commenced. This resulted in – among other things – her propellers being changed because they had caused considerable vibration during the vessel’s first year. When the ship was tested afterwards, the annoying vibration was reduced and, to the Italia Line’s delight, the speed seemed to have increased. During these ‘trials’ she reached an immensely impressive 31.59 knots.

The first major problem that struck the Michelangelo occurred on April 12, 1966. When the liner was sailing towards New York she suddenly encountered very bad weather. Waves fifty feet high hit the ship time and again, and the horror culminated when two passengers were swept overboard. When Michelangelo reached New York she displayed a severely damaged forward superstructure, and momentarily repairs were made when in America. Upon arrival in Italy, the ship had her damaged part of the superstructure covered in canvas.

But these sorts of problems were something that ships and shipping companies could cope with. As the 1960s advanced the new threat from the jet airliner became more and more something of a really big problem, even for the Italian liners. The game Italia Line had played when they put Michelangelo and Raffaello in service had proved grossly unprofitable. By 1970, both ships were losing money quickly. On some voyages, the crew outnumbered the passengers. But the Italia Line did not want to give up already. Some suggestions said that the Raffaello were to be transferred to the more profitable South American run, but eventually this was never realised. The Italian government had supported the two ships with giant amounts of money, but as the liners never seemed to recover, they finally withdrew their financial assistance. The Italia Line had nothing to do but to take the Michelangelo and the Raffaello out of service. The last trans-Atlantic voyage the Michelangelo made was in June 1975, when she was packed with ocean liner buffs who tried to give her the honour of being something else than empty on her final crossing. One of those who wanted to pay a last tribute was the Duchess of Windsor.

When Michelangelo had returned from this last voyage she was laid up in Genoa and then La Spezia. The move to La Spezia, feared many fans, was the ship’s last one because the largest scrapyard in the Mediterranean area was situated there. It seemed that the Michelangelo’s life would last only for ten years.

Fortunately, after several shipping companies had eyed the sisters for a possible purchase but considered them too large, the Michelangelo found herself a buyer. The Shah of Iran was officially given the ownership of the vessel in February 1977. He intended to use her as a permanently moored military barracks. The Michelangelo left Genoa on July 8 the same year and sailed through the Suez channel, past Saudi Arabia before she finally reached her new home in Bandar Abbas on the 21st. In the Shah’s presence, the Iranian flag was hoisted, as the ship became an ‘Iranian citizen’. The Michelangelo, who luckily had escaped the ceremony of renaming, was rebuilt so that she could accommodate 1,800 military personnel.

The Michelangelo continued in this role for another fifteen years, but in 1991 the ship was considered too old and was towed to Pakistan where she was scrapped.

Specifications

- 902 feet (275.5 m) long

- 102 feet (31.2 m) wide

- 45,911 gross tons

- Steam turbines powering two propellers

- 26.5 knot service speed

- Passenger capacity of 1,775 people