1965 – 1983

By the end of the 1950s, aeroplanes were beginning to dominate on the illustrious Atlantic trade. Proud ships as the Cunard Line’s two Queens and French Line’s distinguished old Liberté, built in 1930, sometimes carried close to no passengers at all. When they did, the crew outnumbered the number of passengers most of the time. The remarkable fleet that had once totally dominated the North Atlantic had been turned into ghost ships.

However, many conservative shipping lines would not admit defeat to the air liners and continued to produce great ships. The French Line commissioned the enormous France in 1962. She was intended as a pure trans-Atlantic liner, but she would within short be dependent on heavy subsidies from the French government.

The Italian Line had commissioned the Leonardo da Vinci in 1960. She had been a replacement for the lost Andrea Doria, but by the time she entered service the ocean liner trade on the North Atlantic were losing money rapidly to the airliners.

At the same time, the Italian Line considered the construction of two new liners for the trans-Atlantic run. This utter futility could only be explained with the fact that the shipping line’s directors were trapped in the old way of thinking. They figured Italy would need new superliners to compete on the oceans.

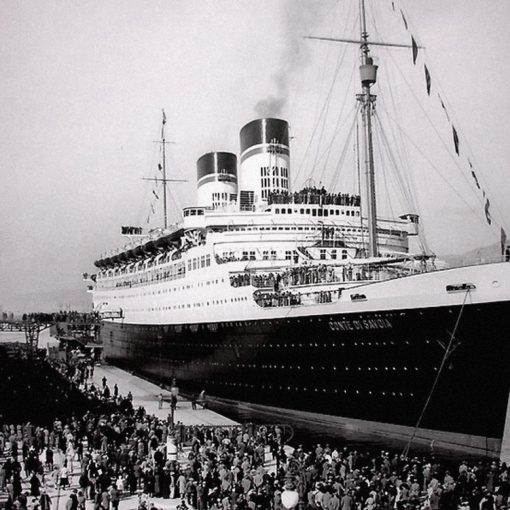

The first sketches of what would later become the Michelangelo and Raffaello were drawn already in 1958. They showed two ships with black hulls and with two conventional funnels each. But instead of the traditional look, the Italian Line decided they would go for something more modern. The final sketches showed two white-hulled ships with two strange-looking, lattice-like funnels, placed far aft. Those lattice-funnels were from the beginning intended for the sister ships Guglielmo Marconi and Galileo Galilei, but their owners – Lloyd Triestino – had not approved of the design. The original style was designed by Professor Mortarino of Turin Polytechnic.

Even though the airlines were taking over the North Atlantic, the Italian Line management would not admit defeat and started construction of the two longest Italian liners ever. The first of the ships was constructed at the famous Ansaldo Shipyard in Sestri Ponente and the second vessel at CR dell’Adriatico at Trieste. On September 16, 1962 the first of the duo – the Michelangelo – was launched. Some five months later, on March 24, 1963, her sister followed. Construction of the two ships continued until April 1965, when the Michelangelo was completed. She set out on her maiden voyage between Genoa and New York on May 12.

The Raffaello was not far behind. In July she was completed, and on the tenth of that same month, she made her first voyage, a Mediterranean cruise. That cruise had merely been a warm-up for her maiden voyage that started on July 25 between Genoa and New York.

The Michelangelo and Raffaello never earned a single lira in profit for the Italian Line, but one cannot deny that the sisters were one of the most beautiful and comfortable ships ever built. The Italians showed that they still were able to produce first class ships for a worldwide market. The staterooms and the public rooms on board the liners offered the passenger unlimited luxury. There were at least one private shower and toilet in every cabin, and on the ship there were altogether six swimming pools – three for adults and three for children. The first class ballroom aboard the Raffaello was dominated by huge crystal chandeliers, and the ship’s two luxury suites were equipped with a large television in each room.

But being large and beautiful did not keep the Raffaello out of trouble. On October 31, 1965, she suffered a severe engine room fire, which made her limp back to Genoa on one propeller, and in May 1970 she collided with a tanker in Algeciras Bay.

Even though the Michelangelo and the Raffaello did not make any money for the owners, they were ‘kept alive’ by the Italian Government’s generous subsidies. But after nine years in service – in 1974 – the North Atlantic operations almost ceased. From then on the Raffaello was used mainly for cruising.

Unfortunately, cruising was not the cure for the Raffaello. She, along with her sister, continued to lose money. After some time, the Italian Government declared to the Italian Line that keeping their subsidy was an impossibility. The two ships had entirely relied on this money and now they were forced to stop sailing. On April 21, 1975, the Raffaello made her last cruise out of New York towards lay up, and the Michelangelo followed less than three months later. On June 6, the Raffaello had reached La Spezia where she would be laid up, all too close to the infamous scrapping yard.

However, the Raffaello’s destiny was not to be scrapped at La Spezia. In 1976, the successful owner of the Home Lines approached the Italian Line and offered a more than reasonable price for the two ships – he wanted to put the sisters back into service in American cruise services, keeping the Italian crew. But the Italian Line would not hear of it. The wanted to get rid of the two embarrassing money-losers – they wanted them out of the country. And so, the ships stayed in Italy until the end of the year when another buyer emerged. It was the Shah of Iran’s government who wanted them for use as accommodation ships for army personnel, oil workers and navy trainees. The Italian Line saw no obstacles, and in December the ships were sold.

Upon arrival in Iran, the Michelangelo was moored at Bandar Abbas, and the Raffaello at Bushire. The Raffaello remained on the spot until a few years into the Eighties. During this period, the ship was neglected and fell into a poor state – rat infested and sun scorched. She would probably have remained there until she fell apart or the scrappers took her, but the never-ending hostilities between Iran and Iraq resulted in an air attack on Bushire in February 1983. During this devastating attack, the Raffaello was hit and slowly sank in the harbour waters. No breaking up of the ship ever commenced and she remains there until this day, although reportedly not visible above the surface. The remnants of the Raffaello can, however, be glimpsed in satellite photos. On Google Maps, for instance, one can see the ship surrounded by white buoys, warning other vessels of the wreck.

Specifications

- 904 feet (276.2 m) long

- 99.1 feet (30.3 m) wide

- 45,933 gross tons

- Geared Ansaldo turbines powering two propellers

- 26.5 knot service speed

- Passenger capacity of 1,775 people

8 thoughts on “Raffaello”

The Ships were beautiful!!! We sailed from New York to Portugal to Sicily to the Port of Naples where we got off in 1967 💚🤍❤️

I was on this ship with my family in January 1966. We arrived in New York City (not sure what pier) on January 18, 1966, having sailed from Italy. It’s strange to me that I can not find any passenger lists on line, not even on ancestry.com, with the passenger lists. My parents remember clearly, sailing from the port of Naples, as do I. We even have a photograph of the four of us sitting in the dining room. The National Archives have not offered much help. In fact, it was easier to find the manifest of my uncle who visited America in 1911. If you can offer any help or suggestions it would be greatly appreciated.

Hello Dina.

Unfortunately, we don’t know much about genealogy or how to find passenger lists. We have a few links to various online resources in our FAQ-section, but I get the impression that you may have tried those options already…

Hello Dina,

We emigrated from France on the Raffaello in December 1965, just a few weeks before your trip (the ship stopped at Cannes before travelling to Genoa, Napoli, Gibraltar and New York). Two years ago, I emailed the National Archives and Records Administration, which collects all such info, to obtain the passenger lists from the Raffaello for that month (Dec. 1965). Oddly, there are comprehensive records of passenger lists for ships coming into New York up to 1957, and post-1967 — but nothing in between, so you and I are both out of luck, at least for now.

I received (to my amazement within a day or two) a phone call from a William Creech (william.creech@nara.gov), who explained that arrival records for 1965 (and therefore 1966) are in the process of being digitized, as the INS destroyed the badly decomposing original paper copies after microfilming them.

He also said to consult Ancestry.com regularly, as they would be among the first to receive the information once the digitization process is done. It’s been two years and still nothing, but just thought I’d let you know how you can keep trying to find out periodically.

Best regards,

François

Hello François,…I forgot all about this query and just happened upon it today. Thank you for answering. So we are still “in the same boat,” so to speak , as I have gotten the same answer from Mr Creach. The last time so checked for an update, there was no reply. If you have gotten any answers and could please share, I would appreciate it. Until then, best of luck and happy holidays to you.

I’m looking for the same also with no luck

we sailed from Athens to Naples (maybe other ports). to NYC. July 1966 on an Italian liner. Could it have been the Raffaello or Michaelangelo?

That would have been on the Cristoforo Colombo