1957 – 1975

Also known as Ocean Monarch

When the Second World War finally came to an end in 1945, the world could look back on six years of terrible carnage and destruction. Cities and countries had been bombed, soldiers had perished in the battlefields and millions had died in Nazi concentration camps. The merchant fleets of the world had also suffered massive damage. Passenger liners converted into troop transports had facilitated the spread of the conflict to a global scale, but many of them had been lost in the process. Although ships such as Cunard’s two Queens made it through the war alive, others had not been so fortunate. The largest allied loss had been the sinking of the 42,000-ton Canadian Pacific liner Empress of Britain in 1940, and Germany had lost ships like the Cap Arcona and Wilhelm Gustloff.

Subsequently, following the Armistice, the shipping lines had to try and rebuild their fleets. But the war had been costly, and the lack of raw material and labour was evident. Instead, some shipping companies were given German ships as reparation for their losses during the war. The French Line, for instance, was given the German express liner Europa and turned her into their new flagship Liberté. But in spite of such great additions, new tonnage was urgently needed.

After some ten years of financial recuperation, Europe was approaching its pre-war status by the mid-1950s, much thanks to the aid of the Marshall-plan. Finally, there were enough funds and capacity to start building new ships. One of the companies that set out to do so was Canadian Pacific, which commissioned two new liners for their Liverpool-Montreal service. The two ships were to be built by separate yards, but they were intended as virtually identical sisters.

While the first ship was built by Fairfield SB & Engineering Company of Govan, the second was laid down as yard no. 155 at Vickers-Armstrong Ltd., Newcastle. These new ships were to be modern and stylish, becoming the prime vessels of Canadian Pacific. And the company did not save their money in achieving just that – the two liners would cost them £5,500,000 each.

On May 9th 1956, the second ship was launched by Lady Eden, wife of the British Prime Minister. The new liner was given the name Empress of England. Canadian Pacific had operated a great number of Empresses in their time, but this was oddly the first time a ship had been given this particular name. As the second ship of a duo, the Empress of England was about a year after her older sister, which had just entered service as the Empress of Britain a month earlier.

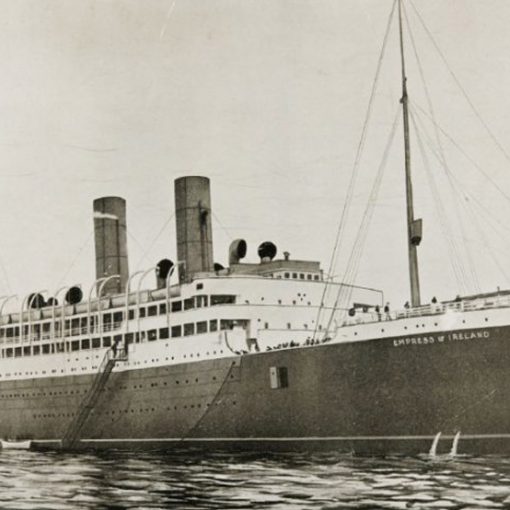

Following the successful launch, the Empress of England was to be fitted out. In many aspects, she would become the state-of-the-art of ocean liners at the time. She was, for example, air-conditioned throughout – along with her sister the first British ships with that distinction. In fact, this feature made some people speculate that the two liners had originally been intended for Pacific service, but it is more likely that it was done in anticipation of the ships’ cruising purposes. Another feature was that the ships were able to answer the helm at speeds as low as five knots. This was clearly a precaution, since they were to operate on the 1,000-mile route along the St. Lawrence River to reach Montreal. Canadian Pacific was long since aware of the hazards involved when navigating this route – they had lost the Empress of Ireland in the St. Lawrence back in 1914.

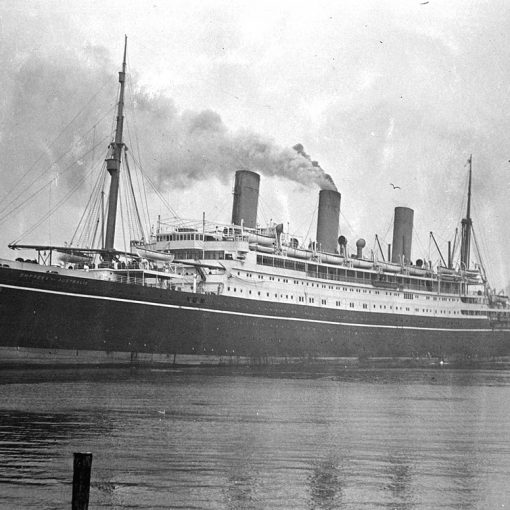

After the Empress of England had been completed and she had gone through her satisfactory sea trials, she was delivered to Canadian Pacific on March 19th, 1957. Luckily for the company, this was just one day before a strike was to be called at the builder’s yard. So with the smallest margin possible, Canadian Pacific managed to avoid possible delay of their latest ship. About a month later, on April 18th, the Empress of England left Liverpool on her maiden voyage, bound for Quebec and finally Montreal. Painted in the Canadian Pacific colours since 1946 – white hull and buff yellow funnel with the company house flag superimposed – she must have been a magnificent sight. The company was now hoping that the Empress of England would perform as well as her sister, Empress of Britain, which by now had been in service for almost exactly a year. The two sisters were outwardly nearly identical, but there were ways of telling them apart. Below the bridge, on boat deck level, the Empress of Britain had six windows in three pairs. Empress of England had only five such windows, arranged two-one-two.

Everything went as planned, and the new Empress’ maiden voyage was a success. Now Canadian Pacific could boast with operating the finest ships on the Canadian run. In the summers, the ships sailed on the Liverpool-Quebec-Montreal route, and in the winters they either terminated their voyages at Saint John or were employed cruising in the Caribbean out of New York. The duo was so successful, that Canadian Pacific soon ordered a third ship for the same service. Named Empress of Canada, this new running mate entered service in April 1961. But although things might have looked good at this moment, the situation was rapidly changing.

Starting in the late 1950s, the ocean liners were faced with a powerful competitor – the aeroplane. Military advances in flight achieved during the war were now being used for commercial purposes, and the aircraft soon became the modern way to travel. Instead of crossing the Atlantic on a ship doing 20-30 knots, one could now fly across with a speed of 500 knots. Many passengers still chose the safe and tested ships in favour of the new aeroplanes, but air traffic were winning over more and more passengers as time went by.

As a result, the Empresses were now spending more and more time doing cruises instead of crossings. And on top of that, Empress of England seemed to be a somewhat unlucky ship. In December of 1962, while in Gladstone Dock the ship broke adrift in a gale and collided with the Common Bros. vessel Hindustan. Both ships’ plating was damaged, and although not very serious, the Empress of England had to go through some extra repairs before she could re-enter service.

Empress of England continued her crossing and cruising service for another few years until October 23rd 1963, when she was chartered to Travel Savings Association (TSA). TSA was a joint venture, funded equally by Canadian Pacific, Royal Mail and Union-Castle Line. On October 28th the Empress of England made her first TSA cruise, and was thereafter employed doing cruises out of Cape Town along with the Empress of Britain.

But by the end of 1964, TSA was beginning to suffer financially. Soon they could no longer afford the charter cost for all the ships, and the business was instead concentrated with the Union-Castle vessel Reina del Mar. And so, on April 18th 1965, Empress of England was released from the charter and returned to Canadian Pacific, who soon put her back on her original Liverpool-Montreal run. But the ship’s bad luck seemed to continue when in November that year she was involved in a collision with a Norwegian tanker in the St. Lawrence estuary. Once again, the damage sustained required repairs before the ship could get back in service.

Continuing her intended service, along with doing cruises in the off-seasons, the Empress of England was part of a company that was going through a great many changes. This was not least evident, when in 1968 Canadian Pacific decided to adopt a new colour scheme for their vessels. The deep-sea fleet was given a green funnel with a white semi-circle and a dark green in-cut triangle. Traditionalists were not very fond of the new livery, they said it was ‘too modern’. But eventually the colours were recognised as a very distinctive and stylish company brand.

However, the Empress of England was only to sport these new colours for a short time. On April 1st 1970 she was withdrawn from service, and sold to Shaw, Savill & Albion only two days later. Renamed Ocean Monarch, the ex-Empress soon found herself in service for her new owners. On April 11th, she made one sailing from Liverpool to Australia, and was then sent to the shipyards of Cammell Laird to be refitted as a full-time cruise ship.

During the refit, the ship was given a complete makeover. Her cargo capacity was removed, as she would not be needing it in her new service. Lido decks and swimming pools were added to her stern area, thereby altering her profile. Her passenger accommodation was changed to a single class with capacity for 1,372 passengers. The entire refit was to become very costly for the ship’s new owners, due to poor circumstances. The cost for the actual refit ended up at £2,000,000 but strikes at the yard cost another £2,000,000. When the ship finally emerged in September 1971, she was six months late and twelve summer cruises had to be cancelled, resulting in a loss of revenues. The Ocean Monarch was intended to do cruises from Southampton to the Mediterranean, but her only such voyage on October 16th that year also became her last in that service.

Instead, the ship was sent to Auckland, from which she operated until 1973 when she started doing Pacific cruises out of Sydney. But by now the end was nigh. The Ocean Monarch was plagued with persistent breakdowns and staff trouble, and this had soon earned her a very bad reputation. She was sent back to Britain, but only to be withdrawn from service in the summer of 1975. On June 13th, the ship left Southampton for the last time. Her destination was Kaohsiung, where she was to be cut up by the breakers.

Specifications

- 640 feet (195.5 m) long

- 85.3 feet (26.1 m) wide

- 25,585 gross tons

- Geared steam turbines turning two propellers

- 20 knot service speed

- Passenger capacity of 1,058 people as originally built, 1,372 people after 1970-71 refit

3 thoughts on “Empress of England”

I was 8 when our family travelled on the Empress of England from Liverpool to Quebec City. This was Summer 1960 but you wouldn’t know it from the weather outside, which was cold and grey the whole crossing. So no-one wanted to play the deck games I’d heard about and had looked forward to. Daytimes were often spent in the indoor pool somewhere near the bottom of the ship. There was a statue of Poseidon or something similar. We could climb onto it. After a couple of days of enjoying the pool there started to be waves in the pool. This was even better fun as the water surged up and down. But then they closed the pool and stopped the enjoyment. That left haunting the shop (with no spending money) or going into the magnificent cinema to watch a film. It wasn’t like today with a wealth of choice on aircraft screens. There were only 2 films a black and white one called the “Gazebo” about a murder, and a colour one called “It Happened to Jane” starring Doris Day as a mother with small kids. That was more approachable. The best scene was when the kids were sent to collect coal from the back of a steam loco. They threw fruit or stones at the train crew, who obliged by throwing coal back! (When I saw this film many years later, this scene had been cut.) I watched each film maybe 4 times as there was so little else to do and the cinema was an exciting dark place.

The meals were fantastic. We could have kids’ food at an early sitting where there was the most wonderful rich creamy porridge, but on the whole I preferred the more grown-up food with Mum and Dad.

A major event was a fancy dress competition. Maybe lots of people came prepared with their costumes, but not Mum and Dad. The crew had been instructed to co-operate with reasonable requests so Dad cadged cocoa powder and a couple of other thing like tea towels. I had no idea what was happening but Dad appeared in his dressing gown and a tea towel as a turban. I think Mum wore a bit less but she was quite glamorous. We kids got dressed in our dressing gowns. The cocoa powder was used to good effect browning our faces. I still didn’t get what was happening, even after Dad carefully wrote a placard emblazoned “An Arab and his Date, and What Came After”. Surprisingly we won the first prize, which was an ash tray picturing the Empress of England. None of us smoked but I still cherish the ash tray.

I was always disappointed the otherwise wonderful ship only had one funnel. Proper ships should have had 3 or even 4 funnels!

In spite of the weather and lack of variety of films it was a wonderful crossing, and I looked forward to the return. But due to something, possibly a dock strike in Liverpool, we came back on a different ship altogether, the Greek Line “Arkadia”. This was very disappointing by comparison. It looked tired and the crew didn’t speak much English. There was a lot more rust. It didn’t smell great and the food wasn’t as good. We got to Southampton OK but I wasn’t surprised when its sister ship the Lakonia had that tragic fire and sinking 2 or 3 years later. I have a dim memory of a really boring life boat drill on the Empress of England – I had hoped and expected that we would be able to get in the life boats – but I can’t remember even a rudimentary drill on the Arkadia. Maybe my childish expectations had been thoroughly damped down by then.

All in all the Empress of England was wonderful!

I sailed out of Greenock in May 1959 on Empress of ( I think it was Empress of France) or Britain. I returned from Montreal in May/June 1960

on the Empress of England. Can’t begin to tell you, what an absolutely, fantastic voyage that was, on both occasions,

Thank you, for the beautiful memories I still have to this day!

I have finally found on the net the complete history of my ship, the Empress of England, on which I worked from 16.8.1966 to 31.5.1968 as a pastry cook. Now I am 77 years old and I still have good memories with all the photos taken during cruises. Max (Switzerland).